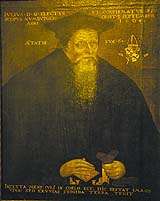

Julius von Pflug

Julius von Pflug (1499 in Eythra – 3 September 1564 in Zeitz) was the last Catholic bishop of the Diocese of Naumburg from 1542 until his death. He was one of the most significant reformers involved with the Protestant Reformation.

Life

He was the son of Cæsar von Pflug, who acted as commissary for the Elector of Saxony in the Leipzig Disputation in 1519.[1] He studied at the universities of Leipzig (1510–17) and Bologna (1517–19), and returned to Germany in 1519 to become canon in Meissen. Disturbed by the religious controversies at home, he returned to Bologna, whence he went to Padua, but in 1521, induced by offers of preferment from Duke George, he returned to his native state, first of all to Dresden, and then to Leipzig, where he still continued to devote himself chiefly to humanistic interests.

In 1528–29 he was again in Italy, and in 1530 he accompanied Duke George to the Diet of Augsburg. At this time he became a correspondent of Erasmus, and in his letters to him unfolded his plan for restoring religious peace to Germany. Everything could be done, he thought, by the influence of moderate men like Erasmus and Melanchthon. Erasmus replied that things had gone so far that even a council could be of no help; one party wanted revolution, the other would tolerate no reform. In 1532 Pflug became dean of Zeitz, where he had to grapple with the practical question of the Reformation, since not only was the bishop, who was also diocesan of Freising, continually absent, but the neighboring Protestant elector of Saxony was alleging claims of jurisdiction over the See.

Pflug was in favor of lay communion under both kinds, the marriage of the priesthood, and general moral reform. He took part in the Leipzig Colloquy in 1534, and as dean of Meissen prepared for the clergy of the diocese the constitutions reprinted in the Leges seu constitutiones ecclesiœ Budissinensis (1573). As one of the envoys of John of Meissen, Pflug endeavored, in 1539, to secure from the papal nuncio, Alexander, who was then at Vienna, adhesion to his project for a reform of Roman Catholicism along the lines already indicated, only to be obliged to wait for the decision of the pope.

The Reformation was now carried through in Meissen, and Pflug took refuge in Zeitz, later retiring to his canonry at Maintz, and thus rendering Zeitz more accessible to the Protestant movement. In 1541 he was appointed bishop of Naumburg, but John Frederick, the elector of Saxony, hating all men of moderation, forbade him to occupy his see. Pflug was uncertain whether he would accept the nomination or not; and meanwhile the elector, after vainly urging the chapter to nominate another bishop, turned the cathedral of Naumburg over to Protestant services and proposed to provide for the election of a bishop according to his liking.

The elector's theologians, though exceedingly dubious regarding his course, finally yielded, and John Frederick selected Nicolaus von Amsdorf for the place and had him ordained by Luther. On 15 January 1542, however, Pflug accepted his election to the bishopric, and sought to have his rights protected by the diets of Speyer (1542, 1544), Nuremberg (1543), and Worms (1545). At the latter diet the emperor directed the elector to admit Pflug to his bishopric, and to repudiate Amsdorf and the secular directors of the chapter. John Frederick refused, however, and the question was settled only by the Schmalkaldic War.

Hitherto Pflug had been in favor of a Roman Catholic reform of a far-reaching character, as was shown by his part at the Regensburg Conference of 1541 where he disputed with Johannes Eck and Johann Gropper; but political conditions and his troubles with the elector of Saxony now made him a bitter opponent of the Reformation. In 1547, when the Schmalkaldic War closed, Pflug took possession of his bishopric under imperial protection. He was a prominent factor in the negotiations which resulted in the Augsburg Interim, the basis of which was formed by the revision of his Formula sacrorum emendandorum by himself, Michael Helding, Johannes Agricola, Domingo de Soto, and Pedro de Malvenda. Pflug now entertained still higher hopes of realizing his reform of Roman Catholicism. He took part in negotiations in Pegau, continuing them in a secret correspondence with Melanchthon to induce him and Prince George of Anhalt to accept a modified sacrificial theory of the Mass; and he was also concerned in the deliberations between Maurice and Joachim II and their theologians at Jüterbog.

The result was the first draft of the Leipzig Interim, which was submitted to the national diet in his presence. In his own diocese Pflug refrained from disturbing the Lutherans, restoring Roman Catholic worship only in the chief church in Zeitz and the cathedral of Naumburg, and even permitting Protestant services to be held in the latter. There was almost an entire dearth of Roman Catholic clergy, nor could he secure a sufficient number from other dioceses. He was accordingly forced to allow the married ministers whom Amsdorf had placed in office to retain their positions, though without Roman Catholic ordination. In November 1551, he was present for a short time at the Council of Trent. Even after the final success of the Protestants in 1552, he remained in undisturbed possession of his see, thanks to his popularity and moderation; and after the abdication of Charles V, he urged the best interests of Germany in his Oratio de ordinanda republica Germaniœ (Cologne, 1562).

In 1557 he presided at the Colloquy of Worms, but was unable to prevent the Flacians from wrecking negotiations. To the last, however, he hoped that, when the Council of Trent reassembled, his moderate program would be successful in restoring religious peace.

References

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Bibliography

- Jacques V. Pollet: Julius Pflug (1499-1564) et la crise religieuse dans l'Allemagne du XVIe siècle Brill Publishers, 1990; ISBN 90-04-09241-2

- Werner Raupp: Julius von Pflug. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Bd. 15, Herzberg: Bautz 1999 (ISBN 3-88309-077-8), cols. 1156–1161.