Julie d'Aubigny

Julie d'Aubigny (1670/1673–1707), better known as Mademoiselle Maupin or La Maupin, was a 17th-century opera singer. Little is known for certain about her life; her tumultuous career and flamboyant lifestyle were the subject of gossip, rumor, and colourful stories in her own time, and inspired numerous fictional and semi-fictional portrayals afterwards. Théophile Gautier loosely based the title character, Madeleine de Maupin, of his novel Mademoiselle de Maupin (1835) on her.

Julie d’Aubigny | |

|---|---|

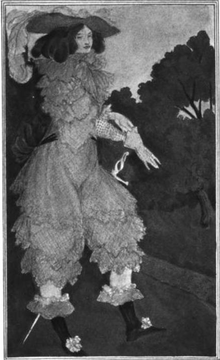

.jpg) "Mademoiselle Maupin de l'Opéra". Anonymous print, c. 1700. | |

| Born | 1670/1673 |

| Died | 1707 (age c. 33) |

| Nationality | French |

| Spouse(s) | Sieur de Maupin |

| Relatives | Gaston d'Aubigny (father) |

Early life

Julie d'Aubigny was born in 1673[1] to Gaston d'Aubigny, a secretary to Louis de Lorraine-Guise, comte d'Armagnac, the Master of the Horse for King Louis XIV. Her father trained the court pages, and so his daughter learned dancing, reading, drawing, and fencing alongside the pages.[2] In 1687, the Count d'Armagnac had her married to Sieur de Maupin of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, and she became Madame de Maupin (or simply "La Maupin" per French custom). Soon after the wedding, her husband received an administrative position in the south of France, but the Count kept her in Paris for his own purposes.

Youth

Also around 1687, D'Aubigny became involved with an assistant fencing master named Sérannes. When Lieutenant-General of Police Gabriel Nicolas de la Reynie tried to apprehend Sérannes for killing a man in an illegal duel, the pair fled the city to Marseille.

On the road south, D'Aubigny and Sérannes made a living by giving fencing exhibitions and singing in taverns and at local fairs. While travelling and performing in these impromptu shows, La Maupin dressed in male clothing but did not conceal her sex. On arrival in Marseille, she joined the opera company run by Pierre Gaultier, singing under her maiden name.

D'Aubigny left for Paris and again earned her living by singing. Near Poitiers, she met an old actor named Maréchal who began to teach her until his alcoholism got worse and he sent her on her way to Paris.[3]

Opera and adult life

The Paris Opéra hired La Maupin in 1690, having initially refused her. She befriended an elderly singer, Bouvard, and he and Thévenard convinced Jean-Nicolas de Francine, master of the king's household, to accept her into the company. She debuted as Pallas Athena in Cadmus et Hermione by Jean-Baptiste Lully the same year. She performed regularly with the Opéra, first singing as a soprano, and later in her more natural contralto range. The Marquis de Dangeau wrote in his journal of a performance by La Maupin given at Trianon of Destouches' Omphale in 1701 that hers was "the most beautiful voice in the world".[3]

In Paris, and later in Brussels, she performed under the name Mademoiselle de Maupin because singers were addressed as "mademoiselle" whether or not they were married.

Until 1705, La Maupin sang in new operas by Pascal Collasse, André Cardinal Destouches, and André Campra. In 1702, André Campra composed the role of Clorinde in Tancrède specifically for her bas-dessus (contralto) range. She sang for the court at Versailles on a number of occasions, and again performed in many of the Opéra's major productions. She appeared for the last time in La Vénitienne by Michel de La Barre (1705).

She retired from the opera in 1705 and took refuge in a convent, probably in Provence, where she is believed to have died in 1707 at the age of 33. She has no known grave.

Gautier's Mademoiselle de Maupin

Théophile Gautier, when asked to write a story about d'Aubigny, instead produced the novel Mademoiselle de Maupin, published in 1835, taking aspects of the real La Maupin as a starting point, and naming some of the characters after her and her acquaintances. The central character's life was viewed through a romantic lens as "all for love". D'Albert and his mistress Rosette are both in love with the androgynous Théodore de Sérannes, whom neither of them knows is really Madeleine de Maupin. A performance of Shakespeare's As You Like It, in which La Maupin, who is passing as Théodore, plays the part of Rosalind playing Ganymede, mirrors the cross-dressing pretense of the heroine. The celebration of sensual love, regardless of gender, was radical, and the book was banned by the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice and authorities elsewhere.

Opera roles created

- Magician in Henri Desmarets's Didon (Paris, 1693)

- Clorinde in André Campra's Tancrède (Paris, 1702)

- Diana and Thétis in Campra's Iphigénie en Tauride (Paris, 1704)

- Mélanie and Vénus in Campra's Alcine (Paris, 1705)

Portrayals

Apart from Gautier's Mademoiselle de Maupin, La Maupin has been portrayed many times in print, stage and screen, including:

- Labie, Charles and Augier, Joanny (1839), La Maupin, ou, Une vengeance d'actrice: comedie-vaudeville en un acte Mifliez, Paris. (In French.)

- La Maupin, the Musical[4] (2017), debuting at 2017 Fresh Fruit Festival in New York City.

- Evans, Henri (1980) Amand and its sequel (1985) La petite Maupin, France Loisirs, Paris. (In French.)

- Dautheville, Anne-France (1995), Julie, chevalier de Maupin J.-C. Lattes, Paris. (In French.)

- Gardiner, Kelly, 2014, Goddess,[5] Fourth Estate/HarperCollins, Sydney (in English)

- Julie, chevalier de Maupin[6] (2004), television mini-series. (In French.)

- Madamigella di Maupin (1966), film. (In Italian.)

References

- Parfaict, F & C (1757). Dictionnaire Des Theatres De Paris, Volume 3. Paris: Lambert. pp. 350-352 - archive.org

- Rogers, Cameron (1928). Gallant Ladies. New York: Harcourt, Brace.

- Gilbert, Oscar Paul (1932). Women In Men's Guise. London: John Lane.

- "La Maupin". Field Musicals. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- http://www.harpercollins.com.au/books/Goddess-Kelly-Gardiner/?isbn=9781460702499

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0393403/

Bibliography

- La Borde, J-B de (1780), Essai sur la musique, iii, 519 ff

- Campardon, E (1884), L'Académie royale de musique au XVIIIe siècle, ii, 177 ff

External link

![]()