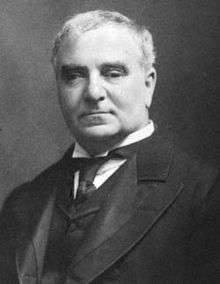

Julian Salomons

The Honourable Sir Julian Emanuel Salomons (formerly Solomons) (4 November 1835 – 6 April 1909) was a barrister, royal commissioner, Solicitor General, Chief Justice and member of parliament. He was the only Chief Justice of New South Wales to be appointed and resign before he was ever sworn into office. Salomons was said to be short of stature and somewhat handicapped by defective eyesight. However, he had great industry, great powers of analysis, a keen intellect and unbounded energy and pertinacity. His wit and readiness were proverbial, and he was afraid of no judge.[1]

Sir Julian Salomons | |

|---|---|

Sir Julian Salomons | |

| Chief Justice of New South Wales | |

| In office 12 November 1886 – 27 November 1886 | |

| Preceded by | Sir James Martin |

| Succeeded by | Sir Frederick Darley |

| Solicitor General | |

| In office 18 December 1869 – 15 December 1870 | |

| Preceded by | Joshua Josephson |

| Succeeded by | William Charles Windeyer |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Julian Emanuel Solomons 4 November 1835 Edgbaston, Warwickshire, England |

| Died | 6 April 1909 (aged 73) Woollahra, New South Wales, Australia |

Early years

Salomons was born at Edgbaston, Warwickshire, England, on 4 November 1835 as Julian Emanuel Solomons. He came to Australia aged 16 years on board the Atalanta on 4 September 1853. He was employed in a book shop and as a stockbroker's clerk. In 1855 he was appointed the secretary of the Great Synagogue at Sydney.

After passing the preliminary examination of the Barristers Admission Board (now the Legal Profession Admission Board) in 1857, he returned to England in 1858 where he entered Gray's Inn and was called to the bar on 26 January 1861. He returned to Sydney and was admitted to the New South Wales Bar on 8 July 1861 and then returned to England to marry his cousin, Louisa Solomons, at Lower Edmonton, Middlesex, England, on 17 December 1862.[2]

Salomons was Jewish and an active member of the Jewish community.[2]

Legal career

He returned to Sydney after his marriage and managed a successful practice as a barrister. He first made a reputation in criminal cases. He had great industry, great powers of analysis, a keen intellect and unbounded energy and pertinacity. However, his passion for work probably led to a decline in his health and he made frequent trips to Europe to recover from these bouts. One of the significant cases he was involved with was the case of Louis Bertrand who was sentenced to death on a charge of murder. Bertrand came to be known as the "Mad Dentist of Wynyard Square". Bertrand had tried to kill Henry Kinder, the husband of his mistress Ellen Kinder on a number of occasions. Bertrand finally shot him, but his shot failed to kill. However, his actions persuaded his mistress to poison Kinder. This was successful. In 1866 Bertrand was convicted of murder and sentenced to death. His mistress was discharged on account of a lack of evidence.[3] Salomons was instructed after the trial and was able to eventually convince the Full Court of the Supreme Court of New South Wales that Bertrand should have a new trial. The decision was tied with two judges for a new trial and two judges against. One judge subsequently retracted his judgment resulting in a win for Salomons. Rather bullishly, Salomons after winning the appeal went further to argue that the judge could not retract his judgment in law. Luckily for his client, the court held that it could and the order for retrial stood.[4] However, the court's decision for a new trial was subsequently overturned on appeal to the Privy Council on the basis that the Supreme Court could not make such an order. The New South Wales Governor commuted Bertrand's sentence to life.

Royal commissioner

In 1870 Salomons was a member of the Law Reform Commission. The purpose of a law reform commission is to make recommendations on updating and changing laws. On 16 August 1881 he was appointed a royal commissioner to inquire into the affairs of the Milburn Creek Copper Mining Co Ltd. Salomons reported on 3 March 1881 that 'there was an appropriation by the trustees themselves, not only without the consent or knowledge of their co-shareholders, but under circumstances of concealment and false statement, evidencing a consciousness on their part, that such appropriation was unauthorised and unjustifiable'.[2] The report was to lead to Ezekiel Alexander Baker, a member of parliament and one of the trustees, being expelled from Parliament.

First parliamentary career

Salomons unsuccessfully ran for parliament in 1869 and instead became Solicitor General in December of that year. He held that position for nearly a year until Sir Charles Cowper took over from Sir John Robertson as premier. He was appointed as a member of the New South Wales Legislative Council, a position he held for six months, before resigning on 14 February 1871.[5]

Appointment as chief justice

Salomons advocacy had earned him a huge reputation. When Chief Justice Sir James Martin died, the position was first offered to William Bede Dalley and then Frederick Matthew Darley. Both refused. Salomons was then offered the position. After some hesitation, Salomons accepted notwithstanding that it involved a substantial reduction in income. His appointment attracted controversy in some quarters and it was reputed that the other judges of the court were against his appointment. Biographer Percival Serle states that Salomons's response to criticism was that his "appointment appears to be so wholly unjustifiable [to Justice William Windeyer ] as to have led to the utterance by him of such expressions and opinions … as to make any intercourse in the future between him and me quite impossible". Serle states that each of the judges of the court denied making any such statements.[1] He had general support with most newspapers and from the legal profession. Nevertheless, he decided on 19 November 1886 to resign the position before actually taking the oath of office. He was therefore gazetted as chief justice for only six days, having resigned twelve days after being offered the position.[2]

Second parliamentary career

He was appointed a second time as a member of the New South Wales Legislative Council on 7 March 1887, holding office for over 11 years until 20 February 1899.[5] During that term, he was vice-president of the Executive Council twice, both for nearly a year between 7 March 1887 and 16 January 1889 and then again between 23 October 1891 and 26 January 1893. He was knighted in 1891 during this second vice-presidency. It was during this second term that it is thought that Salomons gave the longest speech in the history of the council. He spoke for approximately eight hours on the Federation Bill. His speech carried over two days on both 28 and 29 July 1897. The Federation Bill was an important issue in the history of the colony of New South Wales as it led to the birth of the nation of Australia.[6]

Famous quotes

Salomons was reported to have an unusual talent for wit. After the federation of the Australian colonies, the newly established High Court of Australia was said to be routinely overturning decisions of the various Supreme Courts around Australia. Salomons suggested, after appearing before the Supreme Court that the judges of the court should append the following to all Supreme Court judgments: "We are unanimously of the opinion that judgment ought to be entered for (let us say) the plaintiff, but to save the trouble and expense to the parties of an appeal to the High Court, we order judgment to be entered for the defendant."[7]

On the question of Sir Samuel Griffith's English translation of Dante Alighieri which had received numerous unflattering reviews, it was reported that when Griffith presented a copy to Salomons, the latter asked Griffith to autograph the fly leaf, explaining that "I should not like anyone to think that I had borrowed the book, even less should I like anyone to think that I had bought it".[8] Salomons was a supporter of religion being a moderator of human behaviour. He endowed a local public school on the basis that religion was taught as a subject and was upset when it was not. In an address on Australian Federation, he said that having an "education without religion is like putting a sword into the hands of a savage".

Later life

Salomons acted as the agent-general for New South Wales at London between 1899 and April 1900, returning to Sydney the following month.[9] He was also appointed standing counsel for the Commonwealth government in New South Wales in 1903 and all but practically retired from legal practice in 1907. He made a few appearances in court after 1907. He was also a Trustee of Art Gallery of New South Wales and a member of Barristers Admission Board.[5] He died after a short illness on 6 April 1909 of a cerebral haemorrhage in his own home "Sherbourne" in Woollahra, Sydney. He was buried in the Hebrew portion of Rookwood cemetery in Sydney's west.

References

- Serle, Percival. "Salomons, Sir Julian Emanuel (1835 - 1909)". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Project Gutenberg Australia. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- Edgar, Suzanne (1972). "Salomons, Sir Julian Emanuel (1835 - 1909)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne University Press. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 13 September 2007 – via National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- "Henry Louis Bertrand". Law and Justice. Mitchell Library. Archived from the original on 7 September 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- Fitzgerald, John D. "Henry Louis Bertrand". Studies in Australian crime. Gaslight. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- "Sir Julian Emanuel Salomons (1836-1909)". Former Members of the Parliament of New South Wales. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- "Miscellaneous NSW Parliamentary Facts". Parliament of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 17 July 2005. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- Piddington, A B (1929). Worshipful Masters (PDF). Angus & Robertson. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- W.M. Hughes, Policies and Potentates (1950), quoted in: "The Trial of Australia's Last Bushrangers". Lex Scripta. 31 January 2001. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- The Times (36047). London. 24 January 1900. p. 9. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sir James Martin |

Chief Justice of New South Wales 1886 - 1886 |

Succeeded by Sir Frederick Darley |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Joshua Josephson |

Solicitor General 1870 – 1872 |

Succeeded by William Charles Windeyer |