Jules Feiffer

Jules Ralph Feiffer (born January 26, 1929)[1][2] is an American cartoonist and author, who was considered the most widely read satirist in the country.[3] He won the Pulitzer Prize in 1986 as America's leading editorial cartoonist, and in 2004 he was inducted into the Comic Book Hall of Fame. He wrote the animated short Munro, which won an Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film in 1961. The Library of Congress has recognized his "remarkable legacy", from 1946 to the present, as a cartoonist, playwright, screenwriter, adult and children's book author, illustrator, and art instructor.[4]

| Jules Feiffer | |

|---|---|

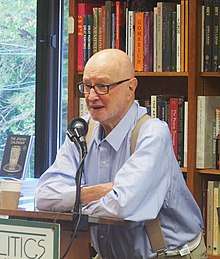

Feiffer in 2018 | |

| Born | January 26, 1929 The Bronx, New York City, New York, United States |

| Nationality | American |

| Area(s) | Cartoonist, author, playwright, screenwriter |

Notable works | Feiffer, Carnal Knowledge, Little Murders, Munro, The Phantom Tollbooth |

| Awards |

|

| Spouse(s) | Judith Sheftel (1961–83; divorced; 1 child) Jennifer Allen (1983 – c. 2013; divorced; 2 children) JZ Holden (2016–present) |

When Feiffer was 17 (in the mid-1940s) he became assistant to cartoonist Will Eisner. There he helped Eisner write and illustrate his comic strips, including The Spirit. He then became a staff cartoonist at The Village Voice beginning in 1956, where he produced the weekly comic strip titled Feiffer until 1997. His cartoons became nationally syndicated in 1959 and then appeared regularly in publications including the Los Angeles Times, the London Observer, The New Yorker, Playboy, Esquire, and The Nation. In 1997 he created the first op-ed page comic strip for the New York Times, which ran monthly until 2000.

He has written more than 35 books, plays and screenplays. His first of many collections of satirical cartoons, Sick, Sick, Sick, was published in 1958, and his first novel, Harry, the Rat With Women, in 1963. He wrote The Great Comic Book Heroes in 1965: the first history of the comic-book superheroes of the late 1930s and early 1940s and a tribute to their creators. In 1979 Feiffer created his first graphic novel, Tantrum. By 1993 he began writing and illustrating books aimed at young readers, with several of them winning awards.

Feiffer began writing for the theater and film in 1961, with plays including Little Murders (1967), Feiffer's People (1969), and Knock Knock (1976). He wrote the screenplay for Carnal Knowledge (1971), directed by Mike Nichols, and Popeye (1980), directed by Robert Altman. Besides writing, he is currently an instructor with the MFA program at Stony Brook Southampton.

Early life

Feiffer was born in The Bronx, New York City, on January 26, 1929. His parents were David Feiffer and Rhoda (née Davis), and Feiffer was raised in a Jewish household with a younger and an older sister.[5] His father was usually unemployed in his work as a salesman due to the Depression. His mother was a fashion designer who made watercolor drawings of her designs which she sold to various clothing manufacturers in New York. "She'd go door to door selling her designs for $3," recalls Feiffer. The fact that she was the breadwinner, however, created an "atmosphere of silent blame" in the home. Feiffer began drawing at the age of 3. "My mother always encouraged me to draw", he says.[6]

When he was 13 his mother gave him a drawing table for his bedroom. She also enrolled him in the Art Students League of New York to study anatomy. He graduated from James Monroe High School in 1947.[7] He won a John Wanamaker Art Contest medal for a crayon drawing of the radio Western hero Tom Mix.[8] He wrote in 1965 about his childhood:

I came to the field with a more serious intent than my opiate-minded contemporaries. While they, in those pre-super days, were eating up "Cosmo, Master of Disguise"; "Speed Saunders"; and "Bart Regan Spy", I was counting up how many panels there were to a page, how many pages there were to a story – learning how to form, for my own use, phrases like: @X#?/; marking for future reference which comic book hero was swiped from which radio hero: Buck Marshall from Tom Mix; the Crimson Avenger from The Green Hornet ...[8]

Feiffer says that cartoons were his first interest when young, "what I loved the most."[9] He states that because he couldn't write well enough to be a writer, or draw well enough to be an artist, he realized that the best way to succeed would be to combine his limited talents in each of those fields to create something unique.[9] He read comic strips from various newspapers which his father might bring home, and was mostly attracted to the way they told stories. "What I loved best about these comics was that they created a very personal world in which almost anything could take place", Feiffer says. "And readers would accept it even if it had nothing to do with any other kind of world. It was the fantasy world I loved."[9]

Among his favorite cartoons were Our Boarding House, Alley Oop and Wash Tubbs.[10] He began to decipher features of different cartoonists, such as the sentimental naturalism of Abbie an' Slats, the [Preston] Sturges-like characters and plots of others, with cadenced dialogue. He recalls that Will Eisner's Spirit rivaled them in structure. And no strip, except [Milton] Caniff's Terry [and the Pirates], rivaled it in atmosphere."[11]

Career

Cartoonist

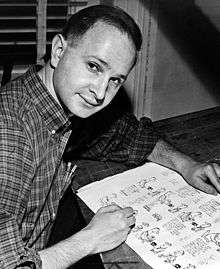

With Will Eisner (1946–1956)

After Feiffer graduated from high school at 16, he was desperate for a job, and went unannounced to the office of one of his favorite cartoonists, Will Eisner. Eisner was sympathetic to young Feiffer, as Eisner had been in a similar situation when he first started out. He asked Feiffer, "What can you do?" He answered, "I'll do anything. I'll do coloring, or clean-up, or anything, and I'd like to work for nothing."[12] However, Eisner wasn't impressed by Feiffer's art abilities and didn't know how he could employ him. But then he decided to give him a low-paying job when he found out that Feiffer "knew more about him than anybody who had ever lived," said Feiffer. "He had no choice but to hire me as a groupie."[12]

Eisner considered Feiffer a mediocre artist, but he "liked the kid's spunk and intensity", writes Eisner biographer Michael Schumacher. Eisner was also aware that they both came from similar backgrounds, despite him being twelve years older. They both had fathers who struggled to support their family, and both their mothers were strong figures who held the family together through hardships.[12] "He had a hunger for comics that Eisner rarely saw in artists", notes Schumacher. "Eisner decided that there was something to this wisecracking kid."[12] When Feiffer later asked for a raise, Eisner instead gave him his own page in The Spirit section, and let him do his own coloring.[7] As Eisner recalled in 1978:

He began working as just a studio man – he would do erasing, cleanup ... Gradually it became very clear that he could write better than he could draw and preferred it, indeed – so he wound up doing balloons [i.e., dialog]. First he was doing balloons based on stories that I'd create. I would start a story off and say, 'Now here I want the Spirit to do the following things – you do the balloons, Jules.' Gradually, he would take over and do stories entirely on his own, generally based on ideas we'd talked about. I'd come in generally with the first page, then he would pick it up and carry it from there.[13]

—Jules Feiffer[12]

They collaborated well on The Spirit, sharing ideas, arguing points, and making changes when they agreed. In 1947, Feiffer also attended the Pratt Institute for a year to improve his art style.[12] Over time, Eisner valued Feiffer's opinions and judgments more often, appreciating his "uncanny knack" for capturing the way people talked, without using contrived dialogue. Eisner recalls that Feiffer "had a real ear for writing characters that lived and breathed. Jules was always attentive to nuances, such as sounds and expressions" which made stories seem more real.[12]

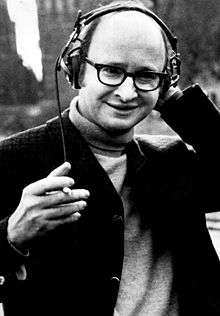

At The Village Voice (1956–1997)

After working with Eisner for nearly a decade, he chose to start creating his own comic strips. In 1956, after again first proving his talent by working for free, he became a staff cartoonist at The Village Voice where he produced the weekly comic strip titled Feiffer. Feiffer's strips ran for 42 years, until 1997, at first titled Sick Sick Sick, then as Feiffer's Fables, and finally as simply Feiffer. After a year with the Voice, Feiffer compiled a collection of many of his satire cartoons into a best-selling book, Sick Sick Sick: A Guide to Non-Confident Living (1958), a dissection of popular social and political neuroses. The success of that collection led to his becoming a regular contributor to the London Observer and Playboy magazine.[3] Director Stanley Kubrick, a fellow Bronx native, invited Feiffer to write a screenplay for Sick, Sick, Sick, although the film was never made.[14] After first becoming aware of Feiffer's work, Kubrick wrote him in 1958:

The comic themes you weave are very close to my heart ... I must express unqualified admiration for the scenic structure of your "strips" and the eminently speakable and funny dialog ... I should be most interested in furthering our contact with an eye toward doing a film along the moods and themes you have so brilliantly accomplished.[15]

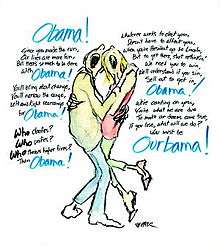

By April 1959, Feiffer was distributed nationally by the Hall Syndicate, initially in The Boston Globe, Minneapolis Star Tribune, Newark Star-Ledger and Long Island Press.[16][17] Eventually, his strips covered the nation, including magazines, and were published regularly in major publications such as the Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Esquire, Playboy and The Nation. He was commissioned in 1997 by The New York Times to create its first op-ed page comic strip, which ran monthly until 2000.

Feiffer's cartoons were typically mini satires, where he portrayed ordinary people's thoughts about subjects such as sex, marriage, violence and politics. Writer Larry DuBois describes Feiffer's cartoon style:

Feiffer had no stories to tell. His main concern was to explore character. In a series of a dozen or so pictures, he would show the shifts of mood that flickered across the faces of men and women as they tried, often vainly, to explain themselves to the world, to their husbands and wives, to their mistresses and lovers, to their employers, to their rulers, or simply to the unseen adversaries at the other end of the telephone wires ... It would be no exaggeration to say that his dialog is as acute as any that is being written America today. Dialog aimed at sophisticated minds, usually with the purpose of shaking them out of sophistication into real awareness.[9]

Feiffer's work is represented by R. Michelson Galleries, located in Northampton, Massachusetts.

Author

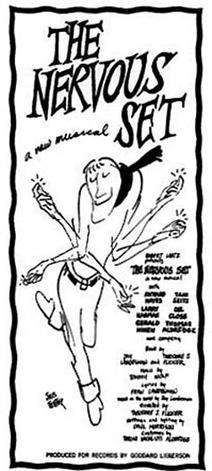

Feiffer published the hit Sick, Sick, Sick: A Guide to Non-Confident Living in 1958 (which featured a collection of cartoons from about 1950 to 1956), and followed up with More Sick, Sick, Sick and other strip collections, including The Explainers, Boy Girl, Boy Girl, Hold Me!, Feiffer's Album, The Unexpurgated Memoirs of Bernard Mergendeiler, Feiffer on Nixon, Jules Feiffer's America: From Eisenhower to Reagan, Marriage Is an Invasion of Privacy and Feiffer's Children. Passionella (1957) is a graphic narrative initially anthologized in Passionella and Other Stories, a variation on the story of Cinderella. The protagonist is Ella, a chimney sweep who is transformed into a Hollywood movie star. Passionella was used in a musical, The Apple Tree.

His cartoons, strips and illustrations have been reprinted by Fantagraphics as Feiffer: The Collected Works. Explainers (2008) reprints all of his strips from 1956 to 1966.[16] David Kamp reviewed the book in The New York Times:

His strip, usually six to eight borderless panels, initially appeared under the title Sick Sick Sick, with the subtitle 'A Guide to Non-Confident Living'. As the Lenny Bruce-ish language suggests, the earliest strips are very much of their time, the postwar Age of Anxiety in the big city; you can practically smell the espresso, the unfiltered ciggies, the lanolin whiff of woolly jumpers.[18]

Feiffer has written two novels (1963's Harry the Rat with Women, 1977's Ackroyd) and several children's books, including Bark, George; Henry, The Dog with No Tail; A Room with a Zoo; The Daddy Mountain and A Barrel of Laughs, a Vale of Tears. He partnered with The Walt Disney Company and writer Andrew Lippa to adapt his book The Man in the Ceiling into a musical.[19] He illustrated the children's books The Phantom Tollbooth and The Odious Ogre. His non-fiction includes the 1965 book The Great Comic Book Heroes.

—Jules Feiffer, Playboy interview[9]

Feiffer also wrote and drew one of the earliest graphic novels, the hardcover Tantrum (Alfred A. Knopf, 1979),[20] described on its dustjacket as a "novel-in-pictures". Like the trade paperback The Silver Surfer (Simon & Schuster/Fireside Books, August 1978), by Marvel Comics' Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, and the hardcover and trade paperback versions of Will Eisner's A Contract with God, and Other Tenement Stories (Baronet Books, October 1978), this was published by a traditional book publisher and distributed through bookstores, whereas other early graphic novels, such as Sabre (Eclipse Books, August 1978), were distributed through some of the first comic-book stores.

His autobiography, Backing into Forward: A Memoir (Doubleday, 2010), received positive reviews from The New York Times[21] and Publishers Weekly, which wrote:

His account of hitchhiking cross-country invades Kerouac territory, while his ink-stained memories of the comics industry rival Michael Chabon's Pulitzer Prize–winning fictional portrait. Two years in the military gave Feiffer fodder for the trenchant Munro (about a child who is drafted). Such satirical social and political commentary became the turning point in his lust for fame, which finally happened, after many rejections, when acclaim for his anxiety-ridden Village Voice strips served as a springboard into other projects.[22]

He has had retrospectives at the New York Historical Society, the Library of Congress and The School of Visual Arts. His artwork is exhibited at and represented by Chicago's Jean Albano Gallery.[23] In 1996, Feiffer donated his papers and several hundred original cartoons and book illustrations to the Library of Congress.[7]

In 2014, Feiffer published Kill My Mother: A Graphic Novel through Liveright Publishing. Kill My Mother was named a Vanity Fair Best Book of 2014 and a Kirkus Reviews Best Fiction Book of 2014. In 2016, Feiffer published Cousin Joseph: A Graphic Novel, a prequel to Kill My Mother. Cousin Joseph was also published through Liveright Publishing, and was a New York Times Bestseller, named one of The Washington Post's Best Graphic Novels of the Year, and was nominated for the Lynd Ward Graphic Novel Prize.

Feiffer's picture book for young readers, Rupert Can Dance, was published by FSG in 2014.

Playwright and screenwriter

Feiffer's plays include Little Murders (1967), Feiffer's People (1969), Knock Knock (1976), Elliot Loves (1990), The White House Murder Case, and Grown Ups. After Mike Nichols adapted Feiffer's unproduced play Carnal Knowledge as a 1971 film, Feiffer scripted Robert Altman's Popeye, Alain Resnais's I Want to Go Home, and the film adaptation of Little Murders.

The original production of Hold Me! was directed by Caymichael Patten and opened at The American Place Theatre, Subplot Cafe, as part of its American Humorist Series on January 13, 1977. The production ran on the Showtime cable network in 1981.[7]

Feiffer moved to Shelter Island, New York in 2017.[24] He wrote the book for a musical based on a story he wrote earlier "Man in the Ceiling" about a boy cartoonist who learned to pursue his dream despite pressures to conform. The musical was produced and directed by Jeffrey Seller in 2017 at the Bay Street Theatre in neighboring Sag Harbor, New York.[25][26][26]

Art instructor

Feiffer is an adjunct professor at Stony Brook Southampton. Previously he taught at the Yale School of Drama and Northwestern University. He has been a Senior Fellow at the Columbia University National Arts Journalism Program. He was in residence at the Arizona State University Barrett Honors College from November 27 to December 2, 2006. In June–August 2009, Feiffer was in residence as a Montgomery Fellow at Dartmouth College, where he taught an undergraduate course on graphic humor in the 20th century.[7]

Personal life

Feiffer has married three times and has three children. His daughter Halley Feiffer is an actress and playwright.[27]

His third marriage took place in September 2016, when he married freelance writer JZ Holden; the ceremony combined Jewish and Buddhist traditions.[28] She is the author of Illusion of Memory (2013).

Honors and awards

- 1961, recipient of a George Polk Awards for his cartoons;[4]

- 1961, film Munro won Academy Award for animated short;

- 1969 and 1970, won Obie Award and Outer Circle Critics Award for plays Little Murders and The White House Murder Case;

- 1986, awarded the Pulitzer Prize for political cartoons[7]

- 1995, elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters;[7]

- 2004, inducted into the Comic Book Hall of Fame; a

- 2004, received the National Cartoonists Society's Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award;[29]

- 2006, received the Creativity Foundation's Laureate[30]

- 2010, won a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Writers Guild of America.[4][31]

Selected works

- Sick, Sick, Sick (1958)

- Passionella and Other Stories (1959)

- The Explainers (1960)

- Boy, Girl, Boy, Girl (1961)

- The Feiffer Album (1962)

- Hold Me! (1962)

- Harry: The Rat with Women, a Novel (1963)

- Feiffer's Album (1963)

- The Unexpurgated Memoirs of Bernard Mergendeiler (1964)

- The Great Comic Book Heroes (1965)

- Feiffer on Civil Rights (1966)

- The Penguin Feiffer (1966)

- Feiffer's Marriage Manual (1967)

- Pictures at a Prosecution (1971)

- Feiffer on Nixon, the Cartoon Presidency (1974)

- Knock Knock (1976)

- Tantrum (1979)

- Jules Feiffer's America: From Eisenhower to Reagan (1982)

- Marriage Is an Invasion of Privacy and Other Dangerous Views (1984)

- Feiffer's Children (1986)

- Ronald Reagan in Movie America (1988)

- The Man in the Ceiling (1993)

- A Barrel of Laughs, A Vale of Tears (1995)

- Meanwhile— (1997)

- I Lost My Bear (1998)

- Backing into Forward: A Memoir (2010)[32]

References

- Comics Buyer's Guide #1650; February 2009; Page 107

- Miller, John Jackson (June 10, 2005). "Comics Industry Birthdays". Comics Buyer's Guide. Archived from the original on February 18, 2011.

- "The Jules Feiffer Interview", The Comics Journal 124, 1988.

- Jules Feiffer, Library of Congress

- Silvey, Ed. The Essential Guide to Children's Books and Their Creators, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (2002) p. 154

- Feiffer, Jules. "The Return of Cartoonist Jules Feiffer", Wall Street Journal, June 16, 2015

- Feiffer, Jules. Backing into Forward: A Memoir, Doubleday, 2010.

- Feiffer, Jules. The Great Comic Book Heroes (The Dial Press, New York, first trade paperback edition, 1977), p. 12. ISBN 978-0-8037-3045-8. Ellipses after "Green Hornet" in original text.

- DuBois, Larry. "Playboy Interview with Jules Feiffer", Playboy magazine, September 1971

- Feiffer, The Great Comic Book Heroes, pp. 12–13

- Feiffer, The Great Comic Book Heroes, p. 13

- Schumacher, Michael. Will Eisner: A Dreamer's Life in Comics, Bloomsbury Publishing (2010) pp. 98–100

- Groth, Gary. "Will Eisner Interview", The Comics Journal No. 46 (May 1979), p. 37. Interview conducted Oct. 13 and 17, 1978

- Kercher, Stephen E., Revel with a Cause: Liberal Satire in Postwar America, Univ. of Chicago (2006) pp. 340–341

- "Hope for America: Performers, Politics and Pop Culture", Library of Congress

- Feiffer, Jules. Explainers: The Complete Village Voice Strips (1956–1966), Fantagraphics Books, 2008.

- "The Press: Sick, Sick, Well" Time, February 9, 1959. WebCitation archive.

- Kamp, David. "Cartoons for Grown-Ups", The New York Times "Sunday Book Review", October 19, 2008. WebCitation archive.

- "Pow! Jules Feiffer's Ceiling Man Hits the Stage", The East Hampton Star, April 21, 2016

- Tallmer, Jerry. "The Three Lives of Jules Feiffer", NYC Plus No. 1, April 2005. WebCitation archive.

- Kakutani, Michiko (March 17, 2010). "From an Artist of Anxiety, an Ink-Stained Memoir". The New York Times.. WebCitation archive.

- "Nonfiction Reviews: 11/30/2009", Publishers Weekly, November 30, 2009. WebCitation archive.

- Jean Albano Gallery – Jules Feiffer. WebCitation archive.

- "Jules Feiffer — A new chapter in a life filling volumes - Shelter Island Reporter". shelterislandreporter.timesreview.com.

- "Andrew Lippa Stars in World Premiere of His Man in the Ceiling Musical Beginning May 30 - Playbill". Playbill.

- Rizzo, Frank (June 9, 2017). "Long Island Theater Review: 'The Man in the Ceiling' by Andrew Lippa and Jules Feiffer".

- Pisarro, Carla (July 7, 2008). "Halley Feiffer's Indie Success on Stage and Screen". The New York Sun. Archived from the original on March 19, 2011. Retrieved March 2, 2009.. .

- "JZ Holden and Jules Feiffer: Humor and Truth Spark Outrage, Then a Union", New York Times, Sept. 17, 2016

- Gardner, Alan. "Jules Feiffer to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award", The Daily Cartoonist, January 30, 2007. Retrieved March 3, 2009. WebCitation archive.

- "2006 Laureate Prize Winner: Jules Feiffer – Arts", Creativity Foundation. WebCitation archive.

- "Writers Guild of America East Press Release".

- Brennan, Elizabeth A.; Clarage, Elizabeth C. Who's Who of Pulitzer Prize Winners, Greenwood Publishing Group (1999) p. 156

External links

- Jules Feiffer illustration represented by R. Michelson Galleries

- Jules Feiffer Official Site, archived from the original on July 21, 2012, retrieved February 12, 2013

- Archival footage of a discussion with Jules Feiffer at a PillowTalk at Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival in 2009

- Lambiek Comiclopedia article.

- Jules Feiffer on IMDb

- Stossel, Sage, "A Conversation With Jules Feiffer", The Atlantic, March 19, 2010. WebCitation archive

- Adams, Sam, "Interview: Jules Feiffer", The A.V. Club, July 28, 2008. WebCitation archive

- Transcript of March 24, 2010, Feiffer interview at the Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art, published as "Backing into Jules Feiffer: An Exclusive Q&A", FilmFestivalTraveler.com, April 18, 2010. WebCitation archive

- Jules Feiffer at Library of Congress Authorities, with 164 catalog records