Sardinian medieval kingdoms

The Judicates (judicadus, logus or rennus in Sardinian, judicati in Latin, regni or giudicati sardi in Italian), in English also referred to as Sardinian Kingdoms, Sardinian Judgedoms or Judicatures, were independent states that took power in Sardinia in the Middle Ages, between the ninth and fifteenth centuries. They were sovereign states with summa potestas, each with a ruler called judge (Sardinian: judike), with the powers of a king.

|

| History of Sardinia |

Historical causes of the advent of the kingdoms

After a relatively brief Vandal occupation (456–534), Sardinia was a province of the Byzantine Empire from 535 until the eighth century.

After 705, with the rapid Arab expansion, pirates from North Africa began to raid the island and encountered no effective opposition by the Byzantine army.[1] In 815, Sardinian ambassadors requested military assistance from the Holy Roman Emperor Louis the Pious.[2]

In 807, 810–812, and 821–822 the Arabs of Spain and North Africa tried to invade the island but the Sardinians resisted several attacks.[3] This defence was so effective that in a letter in 851 Pope Leo IV asked the Iudex Provinciae (judge of the province) of Sardinia, based in Caralis, for aid in the defense of Rome. With the fall of the Exarchate of Africa, based in Carthage, in the eighth century, and especially with the emergence of the Arab presence in Sicily (827), Sardinia remained disconnected from Byzantium and had, out of necessity, become economically and militarily independent.

The birth of the four kingdoms

The almost total absence of historical sources does not allow certainty surrounding the date of the passage from Byzantine central authority to self-government in Sardinia. It is believed that at some point the Iudex Provinciae or Archon of Sardinia, residing in Caralis, had complete control of the island. He appointed, in the most strategic area for the defense of the coast, the lociservator (lieutenant), belonging to his family, the Lacon-Gunale, who became substantially autonomous from Caralis over time; this was probably the action that precipitated the birth of the kingdoms, or judgedoms.[4]

The first incontrovertible source that cites the existence of four kingdoms is the epistle sent by Pope Gregory VII from Capua on October 14, 1073 to the Sardinian judges Orzocco of Cagliari, Orzocco d'Arborea, Marianus of Torres and Constantine of Gallura;[5] however their autonomy was already clear in a later letter of Pope John VIII (872) in which he referred to them as principes Sardiniae ("princes of Sardinia").

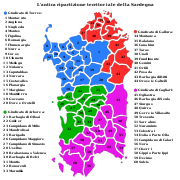

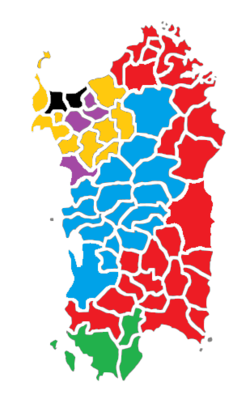

The known medieval giudicati were:

- Kingdom of Cagliari with capital in Santa Igia

- Kingdom of Arborea with capital in Oristano,

- Kingdom of Gallura with capital in Civita,

- Kingdom of Torres with capital in Porto Torres, Ardara and then Sassari.

Each of the four States had fortified borders to protect their political and commercial interests, as well their own laws, administration and emblems.[6]

Governments

The administrative organization of the judgedoms differed significantly from the feudal forms existing in the rest of medieval Europe as their institutions were closer to those of the territories of the Byzantine Empire, although with local peculiarities that some scholars consider of Nuragic derivation.

In the international context of the Middle Ages, the judgedoms were characterized by semi-democratic institutions such as the Coronas de curatorias which in turn elected their own representatives to the parliamentary assizes called Corona de Logu.[7]

The Corona de Logu and the central council

The central government and the entire Judiciary were ruled substantially by the judge. The king did not have possession of the land nor was he the repository of sovereignty since this was formally held by the Corona de Logu, a council of elders (representatives of the administrative districts - Curadorias) and high priests. They appointed the ruler and attributed the supreme power to him, while maintaining the power to ratify acts and agreements related to the entire kingdom.

During su Collectu (coronation ceremony) in the capital, a representative of each curadoria, members of the high clergy, the castle lords, two representatives of the capital elected by delegates from jurados Coronas de curatoria, came together. Then the judex was crowned with a mixed-elected hereditary system following the direct male line and, only in the alternative, the female line.

The judge ruled on the basis of a covenant with the people (the bannus-consensus). The sovereign could be dethroned and even, in cases of serious acts of tyranny and oppression, executed legitimately by the same people, without this prejudging the inheritance of the title within the same ruling dynasty.

Judges

The judge was not an absolute ruler in the sense of later absolutism—at least in form: he could not declare war or sign a peace treaty without the consent of the Corona de Logu. However, that was composed primarily of the nobility's relatives and, therefore, linked by common interests.

The succession to the throne was dynastic but in some case there was the possibility of election by the Corona De Logu.

The judicial chancellery

In the government of the territory, the Judge was assisted by the Chancellery. The sovereign authority was in fact formalized with the drafting of official acts called bullata paper, written by the statal chancellor, usually a bishop or at least a senior member of the clergy, assisted by other officials called majores.

Local administration

Curadorias

The territory of various kingdoms was divided into curadorias, administrative districts of varying sizes formed by urban and rural villages, dependent on a capital which housed the curadore. These administrators, aided especially by jurados (judges) and a council the Corona de curatoria, represented the judicial authority locally and tended to the public property of the Crown.

The curadore appointed for each village was part of the curadorias a majore de Bidda (the modern equivalent of a mayor) with administrative and judicial powers, and direct responsibility for the successful actions of land management.

Law

Judicial army

The Sardinian judicial armies were composed of troops made up of soldiers and free citizens, subject to periodic rotation. In an emergency forced conscription was used. The elite corps was made up of so-called bujakesos, chosen riders who served under the command of the janna de Majore, the commander in charge of the security of the sovereign. The main armaments were the sword, chain mail, the shield, the helmet, and the birrudu, a weapon similar to the ancient verutum, the Roman javelin.

The militias of the ground and the infantry (birrudos) used a shorter version of this same weapon. Besides the use of spears and shields, another common weapon was the leppa, a sword with a bone handle and curved blade, between 50 and 70 cm long which was still in use, in a more contained dimension, until the end of nineteenth century. In Sardinia a type of longbow was made, and over time the use of the crossbow spread.

In case of conflict judges often used mercenary troops, such as the dreaded Genoese crossbowmen.

Culture

Religion

Christianity spread throughout most of the island in the early centuries, excluding much of the Barbagia region. At the end of the sixth century Pope Gregory I reached an agreement with Hospito, chief of the barbaricini, that guaranteed the conversion of his people from paganism to Christianity. Since Sardinia was in the political sphere of the Byzantine Empire, it developed an array of Greek and Eastern Christianity traits as a result of evangelisation by Basilian monks.

The Sardinian Church was an autocephalous institution for five centuries, independent from both the Byzantine and the Roman Curia.[8] In the eleventh century, after the schism of 1054, the judikes, according to Pope Alexander II, began a policy for the development of Western monasticism on the island, with the aim of a wider dissemination of culture but also of new techniques for cultivating the land. The immigration of monastics to the island was fueled by donated funds, and local churches were built by the giudical aristocracy. However, there were still strong ties with the Eastern liturgy. In 1092 a papal bull expressly abolished the autonomy and autocephaly of the Church of Sardinia, which was placed under the primacy of the Archbishop of Pisa.

The first act of donation was made in 1064 by Barisone I of Torres who gave the Benedictine monks of Monte Cassino a large area of its territory with churches (including the Byzantine church of Nostra Segnora de Mesumundu), not far from the then capital of Ardara. For several centuries afterwards representatives of many religious orders including the monks of the Abbey of Montecassino, the Camaldolese, the Vallombrosians, the Vittorini of Marseille, the Cistercians of Bernard of Clairvaux arrived and settled in Sardinia. As a result of this, Romanesque architecture flourished in the island.

Language

Byzantine Greek was used as an administrative language during the Byzantine period, but fell into disuse. Latin, which had long been the language of the native population, developed into the Sardinian language and became the official language. It was also used in legal and administrative documents such as the condaghe, municipal statutes, and the laws of the kingdoms such as the Carta de Logu.

Pisan-Genoese and Aragonese interference and end of the four kingdoms

Pisa and Genoa began to infiltrate the Judicial politics and economy in the eleventh century intervening to support the giudicati, against the Taifa of Dénia, an Iberian Muslim kingdom, which was trying to conquer the island.

From the second half of the thirteenth century the autonomous existence of the kingdoms of Logudoro, Gallura and Calari ended due to the diplomatic maneuvers of Genoa and Pisa on the territory, on trade, on the episcopal curiae, and the judicial chancelleries. The Kingdom of Logudoro ended effectively in 1259 with the direct management of his territories by the Doria and the Malaspina Genoese families. Cagliari was conquered by a Pisan-Sardinian alliance in 1258 and his territory was divided between the winners. Gallura went to the Visconti family and then to Pisa in 1288.

Arborea lasted longer and, between 1323 and 1326, participated in an alliance with the Crown of Aragon at the conquest of the Pisan possessions in Sardinia (the former kingdoms of Gallura and Calari). However, threatened by the Aragonese claims of suzerainty and consolidation of the rest of the island, in 1353 the Kingdom of Arborea, under Marianus IV of Arborea, broke the alliance with the Aragonese and together with the Doria declared war against the Iberians. In 1368 an Arborean offensive succeeded in nearly driving the Aragonese from the island, reducing the Kingdom of Sardinia to just the port cities of Cagliari and Alghero and incorporating everything else into their own kingdom. A peace treaty returned the Aragonese their previous possessions in 1388, but tensions continued. In 1391 the Arborean army, led by Brancaleone Doria, again conquered most of the island, subjecting it to Arborean rule. This state of affairs lasted until 1409, when the army of the Kingdom of Arborea suffered a heavy defeat at the hands of the Aragonese army in the Battle of Sanluri.

The Kingdom of Arborea ceased to exist in 1420, after the sale of its territories to the Aragonese by the last judge, William II of Narbonne, for 100,000 gold florins.

See also

Notes

- Solmi, p. 58.

- Solmi, p. 60.

- Solmi, p. 59.

- Giuseppe Meloni, L’origine dei Giudicati

- Gian Giacomo Ortu, La Sardegna dei Giudici, 2005 p.45

- Francesco Cesare Casula, La politica religiosa del giudicato di Torres, ne I Cistercensi in Sardegna, Nuoro, 1990

- Francesco Cesare Casula, La politica religiosa del giudicato di Torres, ne I Cistercensi in Sardegna, Nuoro, 1990

- Cherchi Paba F., La Chiesa Greca, Cagliari, 1962

Bibliography

English

- Dyson, Stephen L., and Rowland, Robert J. Archaeology and History in Sardinia from the Stone Age to the Middle Ages: Shepherds, Sailors, and Conquerors. Philadelphia: University of Pennsyolvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2007.

- Galoppini, Laura. "Overview of Sardinia History (500–1500)", pp. 85–114. In Michalle Hobart (ed.), A Companion to Sardinian History, 500–1500. Leiden: Brill, 2017.

- Puglia, Andrea. "Interactions Between Lay and Ecclesiastical Offices in Sardinia", pp. 319–30. In Frances Andrews and maria Agata Pincelli (eds.), Churchmen and Urban Government in Late Medieval Italy, c.1200–c.1450: Cases and Contexts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Rowland, Robert J. The Periphery in the Center: Sardinia in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2001.

- Tangheroni, Marco. "Sardinia and Corsica from the Mid-Twelfth to the Early Fourteenth Century", pp. 447–57. In David Abulafia (ed.), The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 5: c.1198–c.1300. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Tangheroni, Marco. "Sardinia and Italy", pp. 237–50. In David Abulafia (ed.), Italy in the Central Middle Ages, 1000–1300. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Zedda, Corrado. "A Revision of Sardinian History between the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries", pp. 115–140. In Michalle Hobart (ed.), A Companion to Sardinian History, 500–1500. Leiden: Brill, 2017.

Italian

- Ortu G.G., La Sardegna dei Giudici, Nuoro, 2005 ISBN 88-89801-02-6

- Birocchi I. e Mattone A. (a cura di), La Carta de logu d'Arborea nella storia del diritto medievale e moderno, Roma-Bari, 2004. ISBN 88-420-7328-8

- AA.VV., Storia dei sardi e della Sardegna, II-III Voll., Milano, 1987-89.

- A. Solmi - Studi storici sulle istituzioni della Sardegna nel Medioevo - Cagliari - 1965

- F. C. Casula - La storia di Sardegna - Sassari 1994

- P. Tola - Codice diplomatico della Sardegna - Cagliari - 1986

- E. Besta - La Sardegna medioevale - Palermo - 1954

- Raffaello Delogu, L'architettura del Medioevo in Sardegna, Roma, 1953, ristampa anastatica, Sassari, 1992.

- F. Loddo Canepa - Ricerche e osservazioni sul feudalesimo sardo - Roma 1932

- G. Stefani - Dizionario generale geografico-statistico degli stati sardi - Sassari - Carlo Delfino Editore

- Alberto Boscolo, La Sardegna bizantina e alto giudicale, Cagliari, 1978.

- Alberto Boscolo, La Sardegna dei Giudicati, Cagliari, Edizioni della Torre, 1979.

- A. Solmi - Studi storici sulle istituzioni della Sardegna nel Medioevo - Cagliari - 1917.

- R. Carta Raspi - La costituzione politico sociale della Sardegna - Cagliari - 1937.

- R. Carta Raspi, Storia della Sardegna, Mursia, 1971.

- R. Carta Raspi, Mariano IV D'Arborea, S'Alvure, 2001.

- R. Carta Raspi, Ugone III d'Arborea e le due ambasciate di Luigi D'Anjou, S'Alvure, 1936.

- M. Caravale - Lo Stato giudicale, questioni ancora aperte, atti del convegno internazionale «Società e Cultura nel Giudicato d'Arborea e nella Carta de Logu» - Oristano - 1995.

- F. C. Casula - Dizionario storico sardo - Sassari - 2003.

- R. Di Tucci - Il diritto pubblico nella Sardegna del Medioevo, in Archivio storico sardo XV - Cagliari - 1924.

- G. Paulis - Studi sul sardo medioevale - Nuoro - Ilisso - 1997.

- Giuseppe Meloni e Andrea Dessì Fulgheri, Mondo rurale e Sardegna del XII secolo, Napoli, Liguori Editore, 1994

- C. Zedda - R. Pinna La nascita dei giudicati. Proposta per lo scioglimento di un enigma storiografico in Archivio storico giuridico sardo di Sassari, seconda serie, volume 12 (2007), pp. 27–118.

- C. Zedda - R. Pinna - La Carta del giudice cagliaritano Orzocco Torchitorio, prova dell'attuazione del progetto gregoriano di riorganizzazione della giurisdizione ecclesiastica della Sardegna, Collana dell'Archivio Storico e Giuridico Sardo di Sassari, nº 10, Sassari 2009.

- C. Zedda – R. Pinna, Fra Santa Igia e il Castro Novo Montis de Castro. La questione giuridica urbanistica a Cagliari all'inizio del XIII secolo, in Archivio Storico e Giuridico Sardo di Sassari, vol. 15 (2010-2011), pp. 125–187.