Joseph Vann

Joseph H. Vann (11 February 1798 – 23 October 1844) was a Cherokee leader of mixed-race ancestry, a businessman and planter in Georgia, Tennessee and Indian Territory. He owned plantations, many slaves, taverns, and steamboats. In 1837, he moved with several hundred Cherokee to Indian Territory, as he realized they had no choice under the government's Indian Removal policy. He built up his businesses along the major waterways, operating his steamboats on the Tennessee, Ohio, Mississippi, and Arkansas rivers.

Joseph Vann | |

|---|---|

Joseph "Rich Joe" Vann | |

| Born | February 11, 1798 Spring Place, Georgia |

| Died | October 23, 1844 near Louisville, Kentucky |

| Occupation | Chief Vann House Owner, Cherokee Leader |

| Spouse(s) | Jennie Springston, Polly Blackburn |

Early life and education

Joseph H. Vann was born at Spring Place, Georgia on February 11, 1798. Joseph and his sister Mary were children of James Vann and Nannie Brown, both Cherokee of mixed-blood, with partial European ancestry. James Vann was a powerful chief in the Cherokee Nation and had several other wives and children. The people were considered one of the Five Civilized Tribes of the American Southeast, because they had adopted some European-American ways, often from traders who intermarried with the Cherokee.

Joseph's paternal grandparents were Joseph Vann, a Scottish trader who came from the Province of South Carolina, and Mary Christiana (Wah-Li or Wa-wli Vann), a Cherokee. Young Joseph was his father's favorite child and was the major heir of his estate and wealth.

At age 11, Joseph was in the room when his father James was murdered in Buffington’s Tavern in 1809 near the site of the family-owned ferry at Spring Place. James Vann had tried to plan to have Joseph to inherit his wealth, but Cherokee law stipulated that the home go to his wife Peggy, while his possessions and property were to be divided among his children.

Eventually the Cherokee Council granted Joseph the inheritance in line with his father's wish; this included 2,000 acres (8.1 km2) of land, trading posts, river ferries, and the Vann House in Spring Place, Georgia. Joseph also inherited his father's gold and deposited over $200,000 in gold in a bank in Tennessee.

Indian Removal

President Andrew Jackson gained Congressional passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, to authorize forced removal of tribes to new lands west of the Mississippi River, in exchange for cession of their lands in the Southeast, to allow development by European-American planters. In 1834 Vann was evicted from his father's Georgia mansion, "Diamond Hill," as part of this process. He moved his large family (he had two wives by then and several children) and business operations to Tennessee.

Vann established a large plantation on the Tennessee River near the mouth of Wolftever Creek, which became the center of a settlement called Vann's Town (later the site of Harrison, Tennessee, and much later, Harrison Bay State Park, Tennessee's first state park). He became known as 'Rich Joe' Vann.

Removal to Indian Territory

In 1837 prior to the main Cherokee Removal, Vann transported a few hundred Cherokee men, women, children, their African-American slaves (including 200 of his own) and horses aboard a flotilla of flat boats to Webbers Falls at the falls of the Arkansas River in Indian Territory. There Vann developed a plantation and directed slaves to construct a replica of his lost Georgia mansion. This building was later destroyed during the American Civil War. Vann also built up his steamboat business, sending his boats throughout the Mississippi tributaries and to New Orleans.

In 1842, 20–25 slaves of Joseph Vann, Lewis Ross, and other wealthy Cherokee at Webbers Falls revolted and fled with guns and horses in an attempt to escape from Indian Territory to Mexico. They picked up 10 more fugitives in Creek territory. A total of 14 slaves were killed or captured in a conflict with a small party of pursuers, who turned back for reinforcements. The other fugitives continued to the south.

They were soon recaptured by a 100-man armed militia of Cherokee posse organized by the Cherokee Council. Five of the fugitives were executed for killing two slavecatchers whom they had encountered, when they freed a slave family being taken back to Choctaw territory. Vann put his surviving slaves to work as crew members of his steamboat, named Lucy Walker after his favorite race horse.

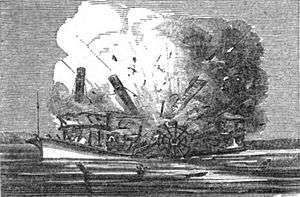

On October 23, 1844, the steamboat Lucy Walker departed Louisville, Kentucky, bound for New Orleans. Below New Albany, Indiana, the vessel was destroyed when one or more boilers blew up. The majority of the passengers, including owner and captain that day, Joseph Vann, were killed.

See also

- James Vann

- Chief Vann House

- Lucy Walker steamboat disaster

References

- 1839 Cherokee Constitution

- Vann, Joseph H., Cherokee Rose: On Rivers of Golden Tears, 1st Books Library (2001), ISBN 0-7596-5139-6.

- Malone, Henry Thompson, Cherokees of the Old South: A People in Transition, University of Georgia Press, (1956), ISBN 0-670-03420-7.

- McFadden, Marguerite, "The Saga of 'Rich Joe' Vann", Chronicles of Oklahoma, Vol. 61 (Spring, 1983).

- McLoughlin, William, Cherokee Renascence in the New Republic, Princeton University Press, (1986), ISBN 0-691-04741-3.

- Perdue, Theda, "The Conflict Within: The Cherokee Power Structure and Removal," Georgia Historical Quarterly, 73 (Fall, 1989), pp. 467–91.

- Young, Mary., "The Cherokee Nation: Mirror of the Republic", (American Quarterly), Vol. 33, No. 5, Special Issue: American Culture and the American Frontier (Winter, 1981), pp. 502–524

External links

- "'Rich Joe' Vann", Our Georgia History]

- Cherokee By Blood

- New Georgia Encyclopedia