Joseph Rizzo

Joseph Rizzo (18th century) was a minor Maltese philosopher and theologian who probably specialised in logic.[1]

Joseph Rizzo | |

|---|---|

| Born | |

| Occupation | Philosophy |

Life

Rizzo was a diocesan priest. He studied theology, and was a professor of philosophy. He taught philosophy in Malta at least between 1781 and 1782. No other information is known as yet about his personal life, and no portrait of him seems to have survived.

Extant work

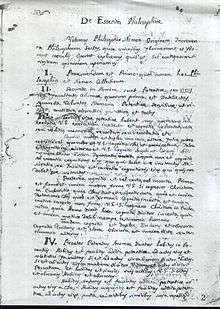

Though Rizzo was no exceptional thinker, his interest and prowess in philosophy is not to be shunned. The only extant writing known to be his is called De Essentia Philosophiæ (Concerning the Essence of Philosophy),[2] and is still in manuscript form.[3] The manuscript, which is in Latin and contains 171 folios, survived as part of the private collection of Fortunatus Panzavecchia. It is not written in Rizzo’s own handwriting, but that of Joseph Ciantar, one of Rizzo’s students. In fact, the document is a report of Rizzo’s lectures given in 1781 through 1782. It is unknown where the lectures were delivered. The division of the work is in the typical style of Scholasticism; in disputes and questions.

The extant manuscript is made up of a nine booklets. However, these probably formed only part of the whole document or documents, for at the beginning it states that it is the first volume (suggesting that other volumes would follow). Unfortunately, the other parts seem to have gone missing. In fact, since the subject-theme of the extant booklets solely concern logic, and the general title certainly suggests that the writing is about more than just logic, it might be concluded that other parts, dealing perhaps with metaphysics, physics, etc., are lost or misplaced.

One of the extant booklets has the title Controversiæ Logices (Controversies concerning Logic). Here Rizzo discusses various points which had been still unresolved during his time. Rizzo states that logic may be divided into institutiones (decided questions) and controversias (undecided questions). One of the latter, on which a discussion was on-going, asked whether Adam had a philosophy. As with others, Rizzo deals with this ‘controversy’ first generally and then particularly. In this particular section, Rizzo decides that Adam did indeed have a philosophy of his own, and gives his arguments to uphold such a doctrine.

The work starts off with an introduction on the nature of philosophy. The rest of the document, apart from the section mentioned above, successively deals with the term ‘logic’; the origins, recognition and growth of logic; and the different schools (‘sects’ he calls them) of logic. Rizzo also deals with the definition of logic, the nature of the work done by the human intellect, and also with the mental (or logical) operations involved in rational mistakes, the source of their processes, and their possible remedies.

References

- Mark Montebello, Il-Ktieb tal-Filosofija f’Malta (A Source Book of Philosophy in Malta), PIN Publications, Malta, 2001, Vol. II, p. 150.

- Ibid., pp. 91-92.

- Archive of the Cathedral, Mdina, MS. Pan.113.

Sources

- Mark Montebello, Il-Ktieb tal-Filosofija f’Malta (A Source Book of Philosophy in Malta), PIN Publications, Malta, 2001.