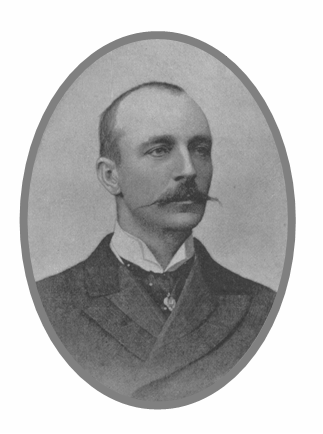

Joseph Moloney

Joseph Moloney (1857 – 5 October 1896) was the Irish-born British medical officer on the 1891–92 Stairs Expedition which seized Katanga in Central Africa for the Belgian King Leopold II, killing its ruler, Msiri, in the process. Dr Moloney took charge of the expedition for a few weeks when its military officers were dead or incapacitated by illness, and wrote a popular account of it, With Captain Stairs to Katanga: Slavery and Subjugation in the Congo 1891–92, published in 1893.[1]

Early career

Born Joseph Augustus Moloney in Newry, Ireland, in 1857, he studied at Trinity College Dublin and St Thomas's Hospital, London. He practised medicine in South London, and was a sportsman and yachtsman, with a taste for adventure, and was said to be 'hard as nails'. He served as a military doctor in the First Boer War in South Africa, and as medical officer on an expedition to Morocco, returning in 1890.[2] On the strength of this, he was appointed by Canadian-born British army officer Captain William Stairs as one of five Europeans on his well-armed mission with 336 African askaris and porters to take possession of Katanga for Leopold's Congo Free State, with or without Msiri's consent.[3]

With Captain Stairs to Katanga

The expedition took a year for the round trip from their base in Zanzibar to Msiri's capital at Bunkeya, where they stayed nearly two months. They suffered disease, starvation for a while, and numerous hardships. A quarter of the Africans and two out of the five Europeans died, including Captain Stairs, but Moloney was spared any severe illness. In Bunkeya, Msiri refused to sign a treaty accepting Leopold's sovereignty and the CFS flag, and was killed by second officer Omer Bodson who had recklessly confronted Msiri in a situation which he, Bodson, could not control. Msiri's people and his successor as chief, seeing the expedition's greater firepower, bowed to the inevitable and signed the treaty.[4] Katanga became part of Leopold's Congo Free State, which achieved later notoriety as a colonial slave state.

Moloney's book has a significant omission. As evidence of Msiri's 'barbarity', it notes that he placed the heads and skulls of executed enemies and miscreants on poles and the palisades of his boma. An article in French was published in Paris around the same time as Moloney's book in which Moloney's colleague on the expedition, the Marquis Christian de Bonchamps, revealed that after killing him, they cut off Msiri's head and hoisted it on a pole in plain view as a 'barbaric lesson' to his people.[5]

Moloney's character

Moloney was in the main conventional in his approach to his job as expedition medical officer, and loyal to his commander and employer. He displayed the superior attitudes of British officers of that time, making no mention of his Irish birth in his book. At times he wrote appreciatively of many of the Africans on the expedition, particularly 'chief' (meaning supervisor) Hamadi-bin-Malum and some of the Zanzibari askaris and porters. He also went against the conventional wisdom in the colonial service by noting the decency and humanity of many of the Arabs in East and Central Africa, opining that they had a much better relationship with the Bantu people than his British colleagues would admit.[6]

As a doctor, Moloney treated African villagers who were brought to him as much as his medical stores would allow.[1]

On the other hand, in his writing Moloney was untroubled by any notion that the killing of Msiri might have been unjustified or that the seizing of Katanga for Leopold was theft of territory. He wrote that Msiri was a bloodthirsty tyrant and despot from whose rule the local people had been liberated by the expedition, and that Bodson had killed Msiri in self-defence.[7]

He did address the point that as British subjects in the King of Belgium's service, he and Stairs might come into armed conflict with competing British interests (the British South Africa Company of Cecil Rhodes). He wrote that in this eventuality they would discharge their duties to their employer, but he did not consider what other British people might think of this.[8] Moloney did not think of Belgium as a serious rival to the British Empire, unlike France, Germany or Portugal.[9]

Moloney's obituary in The Times of London described him as 'very valiant' and credited his leadership of the expedition, while Captain Stairs was ill and after the death of Bodson, with consolidation of control of Katanga and construction of a strong fort, enabling the following Belgian relief expeditions to establish firm control.[10]

After Katanga

On return to London, Moloney lectured and wrote papers on the geography of the expedition's route, and was appointed a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. He resided in New Malden, south-west London.

In 1895, Dr Moloney returned to central Africa with an expedition, this time with the British South Africa Company (which had been his competitor in the scramble for Katanga) to negotiate treaties with African chiefs in North-Eastern Rhodesia. This was a more peaceful expedition than the Stairs Expedition, and was fairly successful, except in the case of Mpeseni, the Ngoni chief based near what is now Chipata. The Ngoni were of Zulu origin with a similar warrior tradition. Moloney spent two days there with Mpeseni, but left empty-handed.[2][10] (Two years later Mpeseni and his warriors rose in rebellion against the British and were defeated.)

Perhaps because of his later service for the BSAC, or perhaps because his role was considered subordinate, Dr Moloney's reputation does not seem to have been subject to the same hostility that the British in Northern Rhodesia later directed towards the reputation of Captain Stairs for winning Katanga for the Belgians.

Joseph Moloney returned to south-west London but did not have time to enjoy his status as a celebrated explorer: he died at the age of 38, and is buried in Kingston Cemetery in Kingston upon Thames.[2]

References

- Joseph A. Moloney: With Captain Stairs to Katanga: Slavery and Subjugation in the Congo 1891–92. Sampson Low, Marston & Company, London, 1893 (reprinted by Jeppestown Press, ISBN 9780955393655)

- "Fraser/Coleman Family Tree". Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 29 April 2007.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) website accessed 29 April 2007.

- Moloney, 1893: p9.

- Moloney, 1893: Chapter XI.

- René de Pont-Jest: L'Expédition du Katanga, d'après les notes de voyage du marquis Christian de BONCHAMPS, in: Edouard Charton (editor): Le Tour du Monde magazine, also published bound in two volumes by Hachette, Paris (1893). Available online at www.collin.francois.free.fr/Le_tour_du_monde/ Archived 5 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Moloney, 1893: pp.69, 70, 121–2.

- Moloney, 1893: pp.vi, 190.

- Moloney, 1893: pp.11, 131, 208.

- Moloney, 1893: p.12.

- The Times: "Obituary of Dr. Joseph Moloney, L.R.C.P.I., Fellow of the Royal Geographic Society, An Explorer". London, 7 October 1896.

Further reading

- Dr. Steven Woodbridge Kingston and the Congo Ancestors September 2008 pp. 44–46