Askari

An askari (from Swahili and Arabic عسكري ʿaskarī, meaning soldier, or military) was a local soldier serving in the armies of the European colonial powers in Africa, particularly in the African Great Lakes, Northeast Africa and Central Africa. The word is used in this sense in English, as well as in German, Italian, Urdu and Portuguese. In French, the word is used only in reference to native troops outside the French colonial empire. The designation is still in occasional use today to informally describe police, gendarmerie and security guards.[1]

During the period of the European colonial empires in Africa, locally recruited soldiers designated as askaris were employed by the Italian, British, Portuguese, German and Belgian colonial armies. They played a crucial role in the conquest of the various colonial possessions, and subsequently served as garrison and internal security forces. During both World Wars, askari units also served outside their colonies of origin, in various parts of Africa, the Middle East and Asia. In South Africa the term refers to former members of the liberation movements who defected to the Apartheid government security forces.[2]

Etymology

Askari is a loan word from the Arabic عسكري (ʿaskarī), meaning "soldier". The Arabic word is a derivation from the Middle Persian word "lashkar" meaning "army". Words for "(a regular) soldier" derived from these words are found in Azeri, Indonesian, Malay, Somali, Swahili, Turkish and Urdu.

Belgian colonies

In the Belgian Congo, the askaris were organised into the Force Publique. This combined military and police force was commanded by white Belgian officers and non commissioned officers.

British colonies

_Benjamin_Stone.jpg)

The Imperial British East Africa Company raised units of askaris from among the Swahili people, the Sudanese and Somalis. There was no official uniform, nor standardised weaponry. Many of the askaris campaigned in their native dress. Officers usually wore civilian clothes.

From 1895 the British askaris were organised into a regular, disciplined and uniformed force called the East African Rifles, later forming part of the multi-battalion King's African Rifles.[3] The designation of "askari" was retained for locally recruited troops in the King's African Rifles, smaller military units and police forces in the colonies until the end of colonial rule in Kenya, Tanganyika and Uganda during the period 1961–63. After independence, the term Askari continued to be used to refer to soldiers in former British colonies.

German colonies

The German Colonial Army (Schutztruppe) of the German Empire employed native troops with European officers and NCOs in its colonies. The main concentration of such locally recruited troops was in German East Africa (now Tanzania), formed in 1881 after the transfer of the Wissmanntruppe (raised in 1889 to suppress the Abushiri Revolt) to German imperial control.

The first askaris formed in German East Africa were raised by DOAG (Deutsche Ost-Afrika Gesellschaft—the German East Africa Company) in about 1888. Originally drawn from Sudanese mercenaries, the German askaris were subsequently recruited from the Wahehe and Angoni tribal groups. They were harshly disciplined but well paid and highly trained by German cadres who were themselves subject to a rigorous selection process. Prior to 1914 the basic Schutztruppe unit in Southeast Africa was the Feldkompanie comprising seven or eight German officers and NCOs with between 150 and 200 askaris (usually 160)—including two machine gun teams.

Such small independent commands were often supplemented by tribal irregulars or Ruga-Ruga.[4]

They were successfully used in German East Africa where 11,000 askaris, porters and their European officers, commanded by Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck, managed to fight a successful guerilla campaign against numerically superior British, Portuguese and Belgian colonial forces until the end of World War I in 1918.

The Weimar Republic and pre-war Nazi Germany provided pension payments to the German askaris. Due to interruptions during the worldwide depression and World War II, the parliament of the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) voted in 1964 to fund the back pay of the askaris still alive. The West German embassy at Dar es Salaam identified approximately 350 ex-askaris and set up a temporary cashiers office at Mwanza on Lake Victoria.

Only a few claimants could produce the certificates given to them in 1918; others provided pieces of their old uniforms as proof of service. The banker who had brought the money came up with an idea: each claimant was handed a broom and ordered in German to perform the manual of arms. Not one of them failed the test.[5]

Nazi Germany

During World War II, the Germans used the term "askaris" for Red Army, predominantly Russian, deserters and POWs who formed units fighting against the Red Army[6] and in other action on the Eastern front.

Western Ukrainian volunteer units like the Nightingale Battalion, Schuma battalions, and the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS were also called Askari. These battalions were used in many operations during World War II. Most of them were either Red Army deserters or anti-communist peasants recruited from Western Ukrainian rural areas under German occupation.

Italian colonies

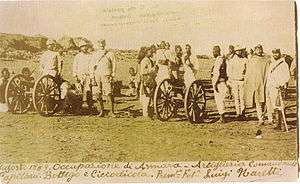

The Italian army in Italian East Africa recruited Eritrean and subsequently Somali troops to serve with Italian officers and some NCOs. These forces comprised infantry, cavalry, camel-mounted and light artillery units. Somali personnel were later recruited to serve with Royal Italian Navy ships operating in the Indian Ocean. The Italian askaris (ascari) fought in the Mahdist War, Battle of Coatit, First Italo–Ethiopian War, Italian-Turkish War, Second Italo-Abyssinian War and in the World War II East African Campaign.

History

Many of the Askaris in Eritrea were drawn from local Nilotic populations, including Hamid Idris Awate, who reputedly had some Nara ancestry.[7] Of these troops, the first Eritrean battalions were raised in 1888 from Muslim and Christian volunteers, replacing an earlier Bashi-bazouk corps of irregulars. The four Indigeni battalions in existence by 1891 were incorporated into the Royal Corps of Colonial Troops that year. Expanded to eight battalions, the Eritrean ascaris fought with distinction at Serobeti, Agordat, Kassala, Coatit and Adwa[8] and subsequently served in Libya and Ethiopia.

Out of a total of 256,000 Italian troops serving in Italian East Africa in 1940, about 182,000 were recruited from Eritrea, Somalia and the recently occupied (1935–36) Ethiopia. When in January 1941, Allied forces invaded Ethiopia in January 1941, most of the locally recruited ascaris deserted. The majority of the Eritrean Ascaris remained loyal until the Italian surrender four months later.

Organisation

Initially the Eritrean Ascaris comprised only infantry battalions, although Eritrean cavalry squadrons (Penne di Falco) and mountain artillery batteries were subsequently raised. By 1922 units of camel cavalry called "meharisti" had been added. Those Eritrean camel units were also deployed in Libya after 1932. During the 1930s Benito Mussolini added some armored cars units to the Ascari.

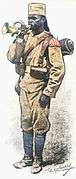

Uniforms

Eritrean regiments in Italian service wore high red fezzes with coloured tufts and waist sashes that varied according to each unit. As examples, the 17th Eritrean Battalion had black and white tufts and vertically striped sashes; while the 64th Eritrean Battalion wore both of these items in scarlet and purple.

White uniforms were worn for parade (see illustration) with khaki for other duties. The Somali ascari were similarly dressed, though with knee length shorts.

Ranks

The Eritrean and Somali Ascari had the following ranks, from simple soldier to senior non commissioned officer: Ascari - Muntaz (corporal) - Bulukbasci (lance-sergeant) -Sciumbasci (sergeant). The Sciumbasci-capos (staff-sergeants) were the senior Eritrean non-commissioned officers, chosen in part according to their performance in battle.

All commissioned officers of the Eritrean Ascari were Italian.[9]

Spanish colonies

As noted above "askari" was normally a designation used in Sub-Saharan Africa. Exceptionally though, the term "askari" was also used by the Spanish colonial government in North-West Africa,[10] in respect not of their regular Moroccan troops (see regulares), but of a locally recruited gendarmerie force raised in Spanish Morocco in 1913.[11] They were known as the "Mehal-la Jalifianas". This was the equivalent of the better known Goumiers employed in French Morocco.

Indigenous members of the Tropas Nómadas or desert police serving in the Spanish Sahara were also designated as "askaris", as were the other ranks of the Native Police (Policia Indígena) raised in Melilla in 1909.[12]

Portuguese colonies

In Portuguese West Africa, and most other African colonies of the Portuguese Empire, local askaris were recruited. These were used to keep the peace in the nation-sized colonies. During the 20th century, all the indigenous troops were merged into a Portuguese colonial army. This military was segregated along lines of race, and until 1960 there were three classes of soldiers: commissioned soldiers (European whites), overseas soldiers (black African "civilizados") and native soldiers (Africans who lived in the Portuguese colonies). These categories were renamed to 1st, 2nd and 3rd class in 1960—which effectively corresponded to the same classification.[13]

Apartheid South Africa

During Apartheid, especially during the 1980s, Askari was the term used to describe former members of the liberation movements who came to work for the Security Branch, providing information, identifying and tracing former comrades. A number were also operationally deployed.[14] Former members of the liberation movements became askaris if they defected from the liberation movements of their own accord or if they were arrested or captured. In some cases, attempts were made to ‘turn’ captured uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK) or Azanian People's Liberation Army (APLA) operatives using both orthodox and unorthodox methods during interrogation, often involving torture. Other askaris were MK operatives who had been abducted by the Security Branch from neighbouring states. Several abductees remain disappeared and are believed to have been killed. The threats of death used to ‘turn’ askaris were not idle. During the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings, amnesty applications revealed that several operatives were killed for steadfastly refusing to co-operate.

Askaris were primarily used to infiltrate groups and to identify former comrades with whom they had trained in other countries. At the Pretoria hearing in July 1999, Mr Chris Mosiane testified: "In the initial stages askaris were used as police dogs to sniff out insurgents with white SB [Security Branch members] as their handlers. Black SB were used to monitor the askaris."[15] Askaris were initially treated as informers and were paid from a secret fund. Later, they were integrated into the South African Police at the level of constable and were paid an SAP salary. While deployed in the regions, they were paid an additional amount, which was usually generated by making false claims to a secret fund. After successful operations they usually received bonuses.[16] The askaris used Vlakplaas as an operational base and resided in the townships where they attempted to maintain their cover as underground MK operatives. Although a few askaris escaped, most were far too frightened to attempt it. At his amnesty hearing, Colonel Eugene de Kock testified that he had set up a spy network amongst the askaris and used electronic surveillance. He told the Amnesty Committee that he had also established a disciplinary structure to deal with internal issues and other infractions by askaris and white officers. However, askaris who exceeded their authority in operational situations or criminal matters were seldom punished. Generally askaris were extremely effective. Because of their internal experience of MK structures, they were invaluable in identifying potential suspects, in infiltrating networks, in interrogations and in giving evidence for the state in trials.[17]

Post 2003 Iraq War

Widely deployed Ugandan private security guards are also designated as askari.[18] Guards were to receive $1,000 monthly salary and an $80,000 bonus if shot, but many have complained that the money was not paid or unfair fees assessed. The guards work for recruiting agencies such as Askar Security Services, which are hired by Beowulf International, a receiving company in Iraq, which subcontracts their services to EOD Technologies, an American company hired by the U.S. Department of Defense to provide security guards for Camp Victory in Baghdad. A Beowulf representative said that 400 of the workers "had impressed the US Army with their skill and experience", but complained that some of the workers lacked police or security experience and "didn't even know how to hold a gun". At least eleven other Ugandan recruiters include Dresak International and Connect Financial Services.[19]

See also

- Lascar

- Sepoy

- Colonial troops

- Belanda Hitam (Zwarte Hollanders), African recruits in the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army

- Force Publique (Belgian Congo)

- Tirailleurs (French Africa)

- Tiradores de Ifni and Regulares (Spanish North Africa)

- Destroyer/distruttore Ascaro (Italian World War II destroyer)

- USS Askari (ARL-30)

References

- Kamusi Project Archived April 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- TRC Final Report, Volume 6, Section 3, Chapter 1 "Key Security Force Units Involved in Gross Human Rights Violations"

- Armies of the 19thC East Africa Chris Peer, Foundry books 2003

- Moyd, Michelle "Askari and Askari Myth" in Prem Poddar et al. Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literatures: Continental Europe and its Colonies, Edinburgh University Press, 2008.

- In Treue fest (July 21, 1975) DER SPIEGEL 30/1975, pp. 64–65

- Reitlinger, Gerald. The SS: Alibi Of A Nation, 1922-1945. Da Capo Press, 1989. at page 126.

- Hagos, Tecola W. ""Ethiopia & Eritrea: Healing Past Wounds and Building Strong People-to-People Relationships" - Disillusionment of International Law and National Strangulations" (PDF). Ethiomedia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- Raffaele Ruggeri, pages 78-79, "Italian Colonial Wars", Editrice Militare Italiana 1988

- Ascari del tenente Indro (in Italian)

- Book image of Spanish "Tropas coloniales" Archived April 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Jose Bueno, page 39"Uniformes de las Unidades Militares de la Ciudad de Melilla" ISBN 84-86629-26-8

- Jose Bueno, page 48 "Uniformes de las Unidades Militares de la Ciudad de Melilla" ISBN 84-86629-26-8

- Coelho, João Paulo Borges, African Troops in the Portuguese Colonial Army, 1961-1974: Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique, Portuguese Studies Review 10 (1) (2002), pp. 129–50

- Kiswahili Radio Report (in Swahili) Archived July 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "Uganda: Askaris in Iraq Ripped Off". New Vision. 2007-08-12.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Askari. |

- Comando Supremo

- African World War II Veterans

- Histoire de la Force Publique (History of the Force Publique) by Lieutenant-General Emile Janssens, Wasmael-Chalier of Namur in 1979

- Ascari: I Leoni di Eritrea/Ascari: The Lions of Eritrea. Eritrea colonial history, Eritrean ascari pictures/photos galleries and videos, historical atlas...

- Ascari of Eritrea Collection of about 200 pictures listed by categories.

- Moyd, Michelle: Askari, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission "Final Report"