Jordan Valley Unified Water Plan

The Jordan Valley Unified Water Plan, commonly known as the "Johnston Plan", was a plan for the unified water resource development of the Jordan Valley. It was negotiated and developed by US ambassador Eric Johnston between 1953 and 1955, and based on an earlier plan commissioned by United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). Modeled upon the Tennessee Valley Authority's engineered development plan, it was approved by technical water committees of all the regional riparian countries—Israel, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria.[1] Though the plan was rejected by the Arab League, both Israel and Jordan undertook to abide by their allocations under the plan. The US provided funding for Israel's National Water Carrier after receiving assurances from Israel that it would continue to abide by the plan's allocations.[2] Similar funding was provided for Jordan's East Ghor Main Canal project after similar assurances were obtained from Jordan.[3]

Background

In the late 1930s and mid 1940s, Transjordan and the Zionist Organization commissioned mutually exclusive, competing water resource development studies. The Transjordanian study, performed by Michael G. Ionides, concluded that the naturally available water resources were not sufficient to sustain a Jewish homeland and the destination of Jewish immigrants. The Zionist's study, by the American engineer Walter Clay Lowdermilk concluded similarly, but noted that by diverting water from the Jordan River basin to the Negev for support of agricultural and residential development there, a Jewish state with 4 million new immigrants would be sustainable.[4]

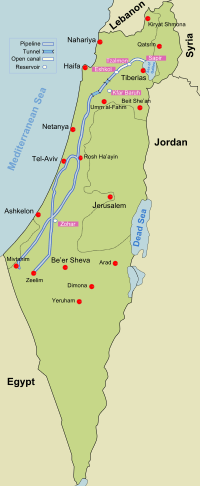

In 1953, Israel began construction of a water carrier to take water from the Sea of Galilee to the populated center and agricultural south of the country, while Jordan concluded an agreement with Syria, known as the Bunger plan, to dam the Yarmouk river near Maqarin, and utilize its waters to irrigate Jordanian territory, before they could flow to the Sea of Galilee.[5] Military clashes ensued, and US President Dwight Eisenhower dispatched ambassador Johnston to the region to work out a plan that would regulate water usage.[6]

Plan

Eisenhower appointed Eric Johnston as a special ambassador on 16 October 1953, and tasked him with mediating a comprehensive plan for the regional development of the Jordan River system.[7] As a starting point, Johnston used a plan commissioned by UNRWA and performed by the American consulting firm Chas. T. Main, known as the "Main Plan". The Main Plan, published just days before Johnston's appointment, utilized the same principles employed by the Tennessee Valley Authority to optimize the usage of an entire river basin as a single unit.[8]

The plan was based on principles similar to those embodied in the Marshall Plan – reducing the potential for conflict by promoting cooperation and economic stability.[7]

The main features of the plan were:

- a dam on the Hasbani River to provide power and irrigate the Galilee area

- dams on the Dan and Banias Rivers to irrigate Galilee

- drainage of the Huleh swamps

- a dam at Maqarin on the Yarmouk River for water storage (capacity of 175 million m³) and power generation,

- a small dam at Addassiyah on the Yarmouk to divert its water toward both the Sea of Galilee and south along the eastern Ghor

- a small dam at the outlet of Sea of Galilee to increase the lake's storage capacity

- gravity-flow canals along the east and west sides of the Jordan valley to irrigate the area between the Yarmouk's confluence with the Jordan and the Dead Sea

- control works and canals to utilize perennial flows from the wadis that the canals cross.[9]

The initial plan gave preference to in-basin use of the Jordan waters, and ruled out integration of the Litani River in Lebanon. The proposed quotas were: Israel 394 million m³, Jordan 774 million m³, and Syria 45 million m³.

Both sides countered with proposals of their own. Israel demanded the inclusion of the Litani river in the pool of available sources, the use of the Sea of Galilee as the main storage facility, out-of-basin use of the Jordan waters, and the Mediterranean-Dead Sea canal. As well, Israel demanded more than doubling of its allocation, from 394 million m³ annually to 810 million m³.

The Arabs countered with a proposal based on the Ionides, MacDonald and Bunger plans, meaning exclusive in-basin use, and rejecting storage in the Sea of Galilee. As well, they demanded recognition of Lebanon as a riparian state, while excluding the Litani from the plan. Their proposed quota allocations were: Israel 200 million m³, Jordan 861 million m³, Syria 132 million m³ and Lebanon 35 million m³ per year.

Negotiations ensued, and gradually the differences were eliminated. Israel dropped the request to integrate the Litani, and the Arabs dropped their objection to out-of-basin use of waters. Ultimately the unified plan proposed the following allocations, by source:

| Source | Lebanon | Syria | Jordan | Israel |

| Hasbani | 35 | |||

| Banias | 20 | |||

| Jordan (main stream) | 22 | 100 | 375 | |

| Yarmouk | 90 | 377 | 25 | |

| Side wadis | 243 | |||

| Total | 35 | 132 | 720 | 400 |

The Plan was accepted by the technical committees from both Israel and the Arab League. A discussion in the Knesset in July 1955 ended without a vote. The Arab Experts Committee approved the plan in September 1955 and referred it for final approval to the Arab League Council. On 11 October 1955, the Council voted not to ratify the plan, due to the League's opposition to formal recognition of Israel. However, the Arab League committed itself to adhere to the technical details without providing official approval.[7]

Later developments

After the Suez Crisis in 1956, however, Arab attitudes hardened considerably,[10] and the Arab League, with the exception of Jordan, now actively opposed the Johnston plan, arguing that any plan to strengthen the Israeli economy only increased the potential threat from Israel.[11] Regardless, both Jordan and Israel undertook to operate within their allocations, and two major successful projects were completed – the Israeli National Water Carrier and Jordan's East Ghor Main Canal (now known as the King Abdullah Canal). Both projects were partially funded by the United States, after Israel and Jordan provided assurances they would abide by their allocations. In 1965, president Nasser too, assured the American under Secretary of state, Philip Talbot, that the Arabs would not exceed the water quotas prescribed by the Johnston plan.[qt 1] At this point, the other Arab states resolved to reduce the operation of Israel's National Water Carrier by diverting the headwaters of the Jordan, leading to a series of military clashes which would help precipitate the 1967 Six-Day War.[7][12]

References

- The UNRWA commissioned a plan for the development of the Jordan River; this became widely known as "The Johnston plan". The plan was modelled on the Tennessee Valley Authority development plan for the development of the Jordan River as a single unit. Greg Shapland, (1997) Rivers of Discord: International Water Disputes in the Middle East, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 1-85065-214-7 p 14

- Sosland, Jeffrey (2007) Cooperating Rivals: The Riparian Politics of the Jordan River Basin, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-7201-9 p 70

- Water Resources in Jordan, Munther J. Haddadin, editor, RFF Press, 2006

- Water Resources in Jordan, Munther J. Haddadin, pp. 237–238, Resources for the Future, 2006

- Water Resources in Jordan, Munther J. Haddadin, p. 239, Resources for the Future, 2006

- Water Resources in Jordan, Munther J. Haddadin, p. 32, Resources for the Future, 2006

- Masahiro Murakami, Managing Water for Peace in the Middle East: Alternative Strategies, Appendix C: "Historical review of the political riparian issues in the development of the Jordan River and basin management," United Nations University Press, 1995

- The UNRWA commissioned a plan for the development of the Jordan River; this became widely known as "The Johnston plan". The plan was modelled on the Tennessee Valley Authority development plan for the development of the Jordan River as a single unit. Greg Shapland, (1997) Rivers of Discord: International Water Disputes in the Middle East. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 1-85065-214-7 p 14

- Managing water for peace in the Middle East

- Shlaim, Avi (2000): The Iron Wall, Penguin Books, pp. 186–187, ISBN 0-14-028870-8

- Shlaim pp. 230–231.

- Shlaim, p. 235.

Quotes

- Moshe Gat (2003). Britain and the Conflict in the Middle East, 1964–1967: The Coming of the Six-Day War. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-275-97514-2. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

[on 1965]Nasser too, assured the American under Secretary of state, Philip Talbot, that the Arabs would not exceed the water quotas prescribed by the Johnston plan