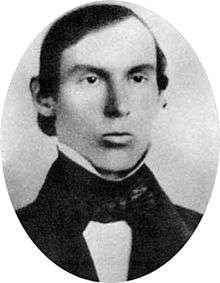

Jones Very

Jones Very (August 28, 1813 – May 8, 1880) was an American poet, essayist, clergyman, and mystic associated with the American Transcendentalism movement. He was known as a scholar of William Shakespeare and many of his poems were Shakespearean sonnets. He was well-known and respected amongst the Transcendentalists, though he had a mental breakdown early in his career.

Jones Very | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | August 28, 1813 Salem, Massachusetts |

| Died | May 8, 1880 (aged 66) |

| Occupation | Essayist, poet and mystic |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

| Literary movement | Transcendentalism |

| Notable works | Essays and Poems (1839) |

Born in Salem, Massachusetts to two unwed first cousins, Jones Very became associated with Harvard University, first as an undergraduate, then as a student in the Harvard Divinity School and as a tutor of Greek. He heavily studied epic poetry and was invited to lecture on the topic in his home town, which drew the attention of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Soon after, Very asserted that he was the Second Coming of Christ, which resulted in his dismissal from Harvard and his eventual institutionalization in an insane asylum. When he was released, Emerson helped him issue a collection called Essays and Poems in 1839. Very lived the majority of his life as a recluse from then on, issuing poetry only sparingly. He died in 1880.

Biography

Very was born on August 28, 1813,[1] in Salem, Massachusetts and spent much of his childhood at sea.[2] He was the oldest of six children, born out of wedlock to two first cousins;[3] his sister Lydia also became a writer. His mother, Lydia Very, was known for being an aggressive freethinker who made her atheistic beliefs known to all.[4] She believed that marriage was only a moral arrangement and not a legal one.[5] His father, also named Jones Very, was a captain during the War of 1812 and was held in Nova Scotia for a time by the British as a prisoner of war.[6] When the younger Jones Very was ten, his father, by then a shipmaster, took him on a sailing voyage to Russia. A year later, his father had Very serve as a cabin boy on a trip to New Orleans, Louisiana. His father died on the return trip,[3] apparently due to a lung disease he contracted while in Nova Scotia.[7]

As a boy, Very was studious, well-behaved, and solitary.[1] By 1827, he left school when his mother told him he must take the place of his father and care for the family. After working at an auction house,[8] Very became a paid assistant to the principal of a private school in Salem as a teenager. The principal, Henry Kemble Oliver, exposed his young assistant to philosophers and writers, including James Mackintosh, to influence his religious beliefs and counteract his mother's atheism.[9] He composed a poem for the dedication of a new Unitarian church in Salem: "O God; On this, our temple, rest thy smile, Till bent with days its tower shall nod".[10]

Harvard years

Very enrolled at Harvard College in 1834.[11] During his college years, he was shy, studious, and ambitious of literary fame. He had become interested in the works of Lord Byron, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller.[4] His first few poems were published in his hometown newspaper, the Salem Observer, while he completed his studies.[11] He graduated from Harvard in 1836, ranked number two in his class.[12] He was chosen to speak at his commencement; his address was titled "Individuality".[11] After graduating, Very served as a tutor in Greek before entering Harvard Divinity School,[2] thanks to the financial assistance of an uncle.[13] Though Very never completed his divinity degree, he held temporary pastorates in Maine, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island.[2]

Very became known for his ability to draw people into literature, and was asked to speak at a lyceum in his hometown of Salem in 1837. There he was befriended by Elizabeth Peabody, who wrote to Emerson suggesting Very lecture in Concord.[14] In 1838, Ralph Waldo Emerson arranged a talk by Very at the Concord Lyceum.[2] Very lectured on epic poetry on April 4 of that year, after he had walked twenty miles from Salem to Concord to deliver it.[14] Emerson made up for the meager $10 payment by inviting Very to his home for dinner.[12] Emerson signed Very's personal copy of Nature with the words: "Har[mony] of Man with Nature Must Be Reconciled With God".[11]

For a time, Very tried to recruit Nathaniel Hawthorne as a brother figure in his life. Though Hawthorne treated him kindly, he was not impressed by Very.[15] Unlike Hawthorne, Emerson found him "remarkable" and, when Very showed up at his home unannounced along with Cornelius Conway Felton in 1838, Emerson invited several other friends, including Henry David Thoreau, to meet him. Emerson, however, was surprised at Very's behavior in larger groups. "When he is in the room with other persons, speech stops, as if there were a corpse in the apartment", he wrote.[16] Even so, in May 1838, the same month Very published his "Epic Poetry" lecture in the Christian Examiner, Emerson brought Very to a meeting of the Transcendental Club, where the topic of discussion was "the question of mysticism".[17] At the meeting, held at the home of Caleb Stetson in Medford, Massachusetts, Very was actively engaged in the discussion, building his reputation as a mystic within that circle.[18]

Mental health

Very was known as an eccentric, prone to odd behavior and may have suffered from bipolar disorder.[19] The first signs of a breakdown came shortly after meeting Emerson, as Very was completing an essay on William Shakespeare. As Very later explained, "I felt within me a new will... it was not a feeling of my own but a sensible will that was not my own... These two consciousnesses, as I may call them, continued with me".[20] In August 1837, while traveling by train, he was suddenly overcome with terror at its speed until he realized he was being "borne along by a divine engine and undertaking his life-journey".[21] As he told Henry Ware Jr., professor of pulpit eloquence and pastoral care at Harvard Divinity School, divine inspiration helped him suddenly understand the twenty-fourth chapter of the Gospel of Matthew and that Christ was having his Second Coming within him. When Ware did not believe him, Very said, "I had thought you did the will of the Father, and that I should receive some sympathy from you—But I now find that you are doing your own will, and not the will of your father".[20] Very also claimed that he was under the influence of the Holy Spirit and composed verse while in this state. Emerson did not believe Very's claim and, noting the poor writing, he asked, "cannot the spirit parse & spell?"[22] Very said he was also tormented by strong sexual desires which he believed were only held in check by the will of God. To help control himself, he avoided speaking with or even looking at women—he called it his "sacrifice of Beauty".[4]

One of Very's students, a fellow native of Salem named Samuel Johnson Jr., said that people ridiculed Very behind his back since he had "gained the fame of being cracked (or crazy, if you are not acquainted with Harvard technicalities)".[20] During one of his tutoring sessions, Very declared that he was "infallible: that he was a man of heaven, and superior to all the world around him".[23] He then cried out to his students, "Flee to the mountains, for the end of all things is at hand".[18] Harvard president Josiah Quincy III relieved Very of his duties, referring to a "nervous collapse" that required him to be left in the care of his younger brother Washington Very, himself a freshman at Harvard.[24] After returning to Salem, he visited Elizabeth Peabody on September 16, 1838,[25] apparently having given up his rule "not to speak or look at women".[26] As she recalled,

He looked much flushed and his eyes very brilliant and unwinking. It struck me at once that there was something unnatural—and dangerous in his air—As soon as we were within the parlor door he laid his hand on my head—and said "I come to baptize you with the Holy Ghost and with Fire"—and then he prayed.[25]

After this, Very told her she would soon feel different, explaining, "I am the Second Coming".[24] He performed similar "baptisms" to other people throughout Salem, including ministers. It was Reverend Charles Wentworth Upham who finally had him committed.[25]

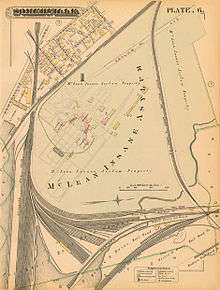

Very was institutionalized for a month at a hospital near Boston,[19] the McLean Asylum, as he wrote, "contrary to my will".[27] While there, he finished an essay on Hamlet, arguing that the play is about "the great reality of a soul unsatisfied in its longings after immortality" and that "Hamlet has been called mad, but as we think, Shakespeare thought more of his madness than he did of the wisdom of the rest of the play".[25] During his stay at the hospital, Very lectured his fellow patients on Shakespeare and on poetry in general.[28]

He was released on October 17, 1838,[25] though he refused to renounce his beliefs. His fellow patients reportedly thanked him as he left.[29] McLean's superintendent Luther Bell took credit for saving him "from the delusion of being a prophet extraordinaire", which Luther thought was caused by Very's digestive system being "entirely out of order".[28] The same month he was released, Very stayed with Emerson at his home in Concord for a week. While he was visiting, Emerson wrote in his journal on October 29, "J. Very charmed us all by telling us he hated us all."[12]

Amos Bronson Alcott wrote of Very in December 1838:

I received a letter on Monday of this week from Jones Very of Salem, formerly Tutor in Greek at Harvard College — which institution he left, a few weeks since, being deemed insane by the Faculty. A few weeks ago he visited me....He is a remarkable man. His influence at Cambridge on the best young men was very fine. His talents are of a high order....Is he insane? If so, there yet linger glimpses of wisdom in his memory. He is insane with God — diswitted in the contemplation of the holiness of Divinity. He distrusts intellect... Living, not thinking, he regards as the worship meet for the soul. This is mysticism in its highest form.[30]

Poetry

Emerson saw a kindred spirit in Very and defended his sanity. As he wrote to Margaret Fuller, "Such a mind cannot be lost".[27] Emerson was sympathetic with Very's plight because he himself had recently been ostracized after his controversial lecture, the "Divinity School Address".[31] He helped Very publish a small volume, Essays and Poems in 1839.[32] The poems collected in this volume were chiefly Shakespearean sonnets. Very also published several poems in the Western Messenger between 1838 and 1840[33] as well as in The Dial, the journal of the Transcendentalists. He was disappointed, however, that Emerson, serving as editor of the journal, altered his poems. Very wrote to Emerson in July 1842, "Perhaps they were all improvements but I preferred my own lines. I do not know but I ought to submit to such changes as done by the rightful authority of an Editor but I felt a little sad at the aspect of the piece."[34] He was never widely read, and was largely forgotten by the end of the nineteenth century, but in the 1830s and 1840s the Transcendentalists, including Emerson, as well as William Cullen Bryant, praised his work.[2]

Very continued writing throughout his life, though sparingly. Many of his later poems were never collected but only distributed in manuscript form among the Transcendentalists.[35] In January 1843, his work was included in the first issue of The Pioneer, a journal edited by James Russell Lowell which also included the first publication of Edgar Allan Poe's "The Tell-Tale Heart".[36]

Final years and death

Jones Very believed his role as a prophet would last only twelve months. By September 1839, his role was complete.[37] Emerson suggested that Very's temporary mental instability was worth the message he had delivered. In his essay "Friendship", Emerson referred to Very:

I knew a man who under a certain religious frenzy cast off this drapery, and spoke to the conscience of every person he encountered, and that with great insight and beauty. At first, all men agreed he was mad. But persisting, he attained to the advantage of bringing every man of his acquaintance into true relations with him... To stand in true relations with men in a false age is worth a fit of insanity, is it not?[38]

The last decades of Very's life were spent in Salem as a recluse under the care of his sister.[2] It was during these years that he held roles as a visiting minister in Eastport, Maine and North Beverly, Massachusetts, though these roles were temporary because he had become too shy. By age 45, he had retired.[39] In his last forty years, Very did very little. As biographer Edwin Gittleman wrote, "Although he lived until 1880, Very's effective life was over by the end of 1840."[40] He died on May 8, 1880 and, upon hearing of Very's death, Alcott wrote a brief remembrance on May 16, 1880:

The newspapers record the death of Jones Very of Salem, Mass. It was my fortune to have known the man while he was tutor in Harvard College and writing his Sonnets and Essays on Shakespeare, which were edited by Emerson, and published in 1839. Very was then the dreamy mystic of our circle of Transcendentalists, and a subject of speculation by us. He professed to be taught by the Spirit and to write under its inspiration. When his papers were submitted to Emerson for criticism the spelling was found faulty and on Emerson's pointing out the defect, he was told that this was by dictation of the Spirit also. Whether Emerson's witty reply, "that the Spirit should be a better speller," qualified the mystic's vision does not appear otherwise than that the printed volume shows no traces of illiteracy in the text.

Very often came to see me. His shadowy aspect at times gave him a ghostly air. While walking by his side, I remember, he seemed spectral, — and somehow using my feet instead of his own, keeping as near me as he could, and jostling me frequently. His voice had a certain hollowness, as if echoing mine. His whole bearing made an impression as if himself were detached from his thought and his body were another's. He ventured, withal, to warn me of falling into idolatries, while he brought a sonnet or two (since printed) for my benefit.

His temperament was delicate and nervous, disposed to visionariness and a dreamy idealism, stimulated by over-studies and the school of thought then in the ascendant. His sonnets and Shakespearean essays surpass any that have since appeared in subtlety and simplicity of execution.[41]

Critical assessment

The first critical review of Very's book was written by Margaret Fuller and published in Orestes Brownson's Boston Quarterly Review; it said Very's poems had "an elasticity of spirit, a genuine flow of thought, and unsought nobleness and purity", though she admitted she preferred the prose in the collection over the poetry.[42] She mocked the "sing song" style of the poems and questioned his religious mission. She concluded: "I am... greatly interested in Mr Very. He seems worthy to be well known."[43] James Freeman Clarke admired Very's poetry enough to have several published in his journal, the Western Messenger, between 1838 and 1840.[33] William Ellery Channing admired Very's poetry as well, writing that his insanity "is only superficial".[44] Richard Henry Dana Sr. also commented positively on Very's poetry: "The thought is deeply spiritual; and while there is a certain character of peculiarity which we so often find in like things from our old writers, there is a freedom from quaintness... Indeed, I know not where you would... find any thing in this country to compare with these Sonnets."[33]

Editor and critic Rufus Wilmot Griswold was impressed enough by Very's poetry to include him in the first edition of his anthology The Poets and Poetry of America in 1842. He wrote to Emerson asking for more information about him and expressing his opinion of his poetry: "Though comparatively unknown, he seems to be a true poet."[45]

The modern reassessment of Jones Very as an author of literary importance can be dated to a 1936 essay by Yvor Winters[46] who wrote of the poet, “In the past two decades two major American writers have been rediscovered and established securely in their rightful places in literary history. I refer to Emily Dickinson and Herman Melville. I am proposing the establishment of a third.”[47] Winters, in speaking of Very's relations with Emerson and his circle, concluded, “The attitude of the Transcendentalists toward Very is instructive and amusing, and it proves beyond cavil how remote he was from them. In respect to the doctrine of the submission of the will, he agreed with them in principle; but whereas they recommended the surrender, he practised it, and they regarded him with amazement.”[48] Subsequently, William Irving Bartlett, in 1942, outlined the basic biographical facts of Very's life in Jones Very, Emerson’s “Brave Saint.”[46] A complete scholarly edition of Very's poetic works belatedly appeared, over a century after the poet's death, in 1993.[49]

Notes

- Gittleman, 5

- Kane, Paul. Poetry of the American Renaissance. New York: George Braziller, 1995: 174. ISBN 0-8076-1398-3

- McAleer, 282

- Packer, 70

- Richardson, 302

- Gittleman, 4

- Gittleman, 8

- Gittleman12

- Gittleman, 12–14

- Marshall, 337

- Baker, 121

- McAleer, 281

- Buell, Lawrence. New England Literary Culture: From Revolution through Renaissance. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989: 388. ISBN 0-521-37801-X

- Packer, 71

- Miller, 140

- McAleer, 281–282

- Packer, 72

- Richardson, 303

- Miller, 139

- Baker, 122

- Marshall, 338

- Gura, 288

- Packer, 79

- Baker, 123

- Richardson, 304

- Gittleman, 276

- Marshall, 344

- Beam, 37

- Packer, 80

- Alcott, Amos Bronson (ed. Odell Shepard). The Journals of Bronson Alcott. Boston: Little, Brown, 1938: 107–108

- Marshall, 345

- Gura, 194

- Gittleman, 354

- Gittleman, 333

- Packer, 81

- Duberman, Martin. James Russell Lowell. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1966: 46–47.

- Gittleman, 360

- Beam, 37–38

- Richardson, 306

- Gittleman, 372

- Alcott, Amos Bronson (ed. Odell Shepard). The Journals of Bronson Alcott. Boston: Little, Brown, 1938: 516–517

- Gittleman, 356–357

- Capper, Charles. Margaret Fuller: An American Romantic Life: The Private Years. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992: 319. ISBN 0-19-509267-8

- Richardson, 305

- Griswold, Rufus W. to Ralph Waldo Emerson. September 18, 1841. Letter in the manuscript collection at Houghton Library, Harvard University.

- Deese, Helen R., Editor. Jones Very: The Complete Poems. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1993: xxxviii.

- Winters,Yvor. “Jones Very: A New England Mystic.” American Review (May 1936): 159.

- Winters,Yvor. “Jones Very: A New England Mystic.” American Review (May 1936): 166.

- Deese, Helen R., Editor. Jones Very: The Complete Poems. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1993.

References

- Baker, Carlos. Emerson Among the Eccentrics: A Group Portrait. New York: Viking Press, 1996. ISBN 0-670-86675-X

- Bartlett, William Irving. Jones Very, Emerson's "Brave Saint." Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1942.

- Beam, Alex. Gracefully Insane: Life and Death Inside America's Premier Mental Hospital. New York: PublicAffairs, 2001. ISBN 978-1-58648-161-2

- Deese, Helen R., Editor. Jones Very: The Complete Poems. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0820314815

- Gittleman, Edwin. Jones Very: The Effective Years: 1833-1840. New York: Columbia University Press, 1967.

- Gura, Philip F. American Transcendentalism: A History. New York: Hill and Wang, 2007. ISBN 0-8090-3477-8

- Marshall, Megan. The Peabody Sisters: Three Women Who Ignited American Romanticism. Boston: Mariner Books, 2005. ISBN 978-0618711697

- McAleer, John. Ralph Waldo Emerson: Days of Encounter. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1984. ISBN 0-316-55341-7

- Miller, Edwin Haviland. Salem Is My Dwelling Place: A Life of Nathaniel Hawthorne. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1991. ISBN 0-87745-332-2

- Richardson, Robert D. Jr. Emerson: The Mind on Fire. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1995. ISBN 0-520-08808-5

- Winters,Yvor. “Jones Very: A New England Mystic.” American Review (May 1936): 159-178.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Jones Very |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jones Very. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Jones Very |

- Works by Jones Very at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Very biography through 1840 from Transcendentalism Web

- Very article from Dictionary of Literary Biography

- Harvard Square Library bio

- Essays and Poems (1839) at Making of America Books

- Essays and Poems (1839) at Google Book Search

- Index entry for Jones Very at Poets' Corner