Divinity School Address

The "Divinity School Address" is the common name for the speech Ralph Waldo Emerson gave to the graduating class of Harvard Divinity School on July 15, 1838.

Background

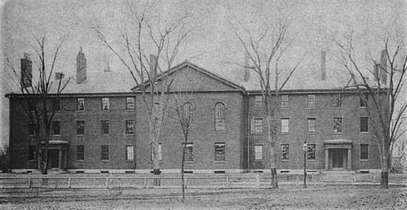

Emerson presented his speech to a group of graduating divinity students, their professors, and local ministers on July 15, 1838, at Divinity Hall.[1] At the time of Emerson's speech, Harvard was the center of academic Unitarian thought. In this address, Emerson made comments that were radical for their time. Emerson proclaimed many of the tenets of Transcendentalism against a more conventional Unitarian theology. He argued that moral intuition is a better guide to the moral sentiment than religious doctrine, and insisted upon the presence of true moral sentiment in each individual, while discounting the necessity of belief in the historical miracles of Jesus.[2]

Emerson's Divinity School address was influenced by his life experiences. He was an ex-Unitarian minister, having resigned from his ministry at Second Church, Boston, in 1832. Emerson had developed philosophical questions about the validity of Holy Communion, also called The Lord's Supper. He believed this ritual was not consistent with the original intentions of Jesus. It is felt that this concern was only one of many philosophical differences with Unitarian beliefs of the 1830s, but it was a concern that could be readily understood by the members of his congregation. Emerson was well liked by his congregation and efforts were made to reconcile the congregation's needs with his philosophy, but Emerson resigned after a final sermon explaining his views.

Over the next few years, Emerson's views continued to drift away from the mainstream Unitarian thought. His biographer Robert Richardson describes him as having moved beyond Unitarianism but not beyond religion. Emerson became a noted lecturer and essayist. He was frequently invited as a guest minister into Unitarian pulpits.

The 1838 Divinity School graduating class was composed of seven seniors, though only six of them were in attendance for the address; Emerson was invited to speak by class members themselves. Emerson decided the time was appropriate to discuss the failures of what he called "historical Christianity". In his address, he not only rejected the notion of a personal God, he castigated the church’s ministers for suffocating the soul through lifeless preaching. Also in attendance were theologians including Andrews Norton, Henry Ware Jr., and Divinity School Dean John G. Palfrey.[3]

Response

Emerson anticipated a scholarly discussion but was completely surprised by the negative outburst which followed. Attacks on Emerson quickly became personal. He was called an atheist, a negative comment in 1838. The chief Unitarian periodical of the time (The Christian Examiner) stated that Emerson's comments, "…so far as they are intelligible, are utterly distasteful to the instructors of the school, and to Unitarian ministers generally, by whom they are esteemed to be neither good divinity nor good sense."

The address touched off a major controversy among American Unitarian theologians, especially among those present, who saw the speech as an attack on their faith.[4] Dissenters primarily addressed the necessity of belief in the historical truth of the Biblical miracles, but the response involved other secondary issues as well. The Unitarian establishment of New England and of the Harvard Divinity School rejected Emerson's teachings outright, with Andrews Norton of Harvard publishing especially forceful retorts, including one calling Transcendentalism "the latest form of infidelity". Henry Ware Jr., one of Emerson's mentors as a divinity student more than a decade prior, delivered the sermon "The Personality of the Deity" on September 23, 1838. Although the sermon was not a direct attack on Emerson, it was written with Emerson in mind and refuted the new tendency to think of God in terms of "divine laws" instead of as a being who plays multiple roles.[5] The sermon was also circulated in printed form.

Notes

- Field, Peter S. Ralph Waldo Emerson: The Making of a Democratic Intellectual. Landham, New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002: 11. ISBN 0847688429

- Divinity School Address Retrieved on 25 November 2017

- Field, Peter S. Ralph Waldo Emerson: The Making of a Democratic Intellectual. Landham, New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002: 12. ISBN 0847688429

- Field, Peter S. Ralph Waldo Emerson: The Making of a Democratic Intellectual. Landham, New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002: 125. ISBN 0847688429

- Wright, Conrad. "Introduction" to Three Prophets of Religious Liberalism: Channing, Emerson, Parker. Boston: Unitarian Universalist Association/Beacon Press, 1986: 30. ISBN 1558962867

References

- Richardson, Robert D. (1995). Emerson: The Mind on Fire. University of California Press.

- Rusk, Ralph L. (1949). The Life of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Trueblood, D. Elton (1939). "The Influence of Emerson's Divinity School Address". The Harvard Theological Review. 32 (1): 41–56.

External links