Jonas Erikson Sundahl

Jonas Erikson Sundahl (1678-1762) was a Swedish-born architect who spent most of his working life at and around Zweibrücken in the German Palatinate. Most of his designs were in the then-modern Baroque style.

Jonas Erikson Sundahl | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 11 or 16 April 1678 Gäserud, Dalsland, Sweden |

| Died | 5 June 1762 (aged 84) Zweibrücken, Germany |

| Nationality | Swedish |

| Occupation | Architect |

Notable work | Schloss Zweibrücken |

Biography

Sundahl's exact date of birth is uncertain. His father was Olaf Erikson Sundahl (1627-1697), a ship's captain.[1] He had two brothers, Mons Erikson and Olaf.

In 1689 - at the age of 11 - he matriculated at Uppsala University. In 1693, his uncle, Brynolph Hesselgreen, called him to Pomerania. In 1698, he was appointed Landmesser (surveyor) in Halland and South Sweden.[2]

The then king of Sweden, Charles XII, was also Duke of Palatinate-Zweibrücken in Germany. In 1702, Gabriel Oxenstierna, Charles' governor in Zweibrücken, asked for the services of an architect.[Note 1] Sundahl relocated to the Palatinate, where he stayed for the rest of his life. His earliest known work dates from that year – improvements to the fortifications of Zweibrücken.

Oxenstierna died in 1707. Charles presumably appointed another governor in his place.

Charles has a warlike reputation. In 1702, he invaded Poland. In 1704, he deposed its king, Augustus II, and installed Stanisław Leszczyński in his place as a client king. In 1709, Stanisław was overthrown by Augustus, was expelled from Poland, and sought refuge in Sweden. In 1714, Stanisław relocated to Zweibrücken, where he remained until 1718. In 1715-1716, Sundahl designed and built a summer palace for Stanisław at Zweibrücken, called Lustschloss Tschifflik,[3] overlooking the Schwarzbach.[Note 2][Note 3] He redesigned and rebuilt buildings at Gräfinthal Abbey, where Stanisław's daughter Anna (died 1717) was buried.

Charles died in 1718. His cousin Gustav (1670-1731) inherited the title of Duke of Zweibrücken. Stanisław left Zweibrücken. It seems that the existing accommodation at Zweibrücken was not to Gustav's liking, because Sundahl spent 1720-1725 designing and building for him Schloss Zweibrücken, perhaps his greatest achievement. From 1720-1725, Sundahl seems to have been chief architect (German: Baumeister) to the court of Zweibrücken. From 1724 or 1725 to 1731 (sources differ for the beginning date),[2] he was subordinated to Charles François Duchesnois.[Note 4] In 1731, he was reinstated to his earlier position.[2][Note 5] He was thereafter again chief architect at Zweibrücken, and was promoted to the rank of chamberlain (German: Hofkammerrat).[2] In 1755, he resigned from his post (he was in his seventies), and was succeeded by his pupil and assistant Christian Ludwig Hautt (1726-1806).

Personal life

On 11 November 1705, Sundahl married Anna Dorothea von Bein (1680-1726), of a patrician family of Frankfurt am Main. They had 13 children, most of whom died young. Their third son, Johann Gottfried Christian, may have been a surveyor in Blieskastel and in the area around Kaiserslautern. On 26 July 1732, Sundahl married Katharina Sophia née Heinztensberger, a widow. There were three children from that second marriage. Sundahl died on 5 June 1762, in Zweibrücken.[2]

Works

Sundahl has been said to have been influenced by the ideas of Swedish architect Nicodemus Tessin the Younger (1654-1728).

Sundahl's works include:[2]

- 1702 – improvements to the fortifications of Zweibrücken

- 1714, 1719 – Gräfinthal Abbey, Mandelbachtal, improvements to the buildings and to the abbey church

- 1715-1716 – Lustschloss Tschifflik, Zweibrücken, a summer palace for Stanisław Leszczyński

- 1716 – Château Barrabino, a dower house in Forbach for Marianne Camasse, Countess of Forbach

- 1717 – Schloss Ditschviller, Cocheren

- 1720 – Gustavsburg, a residence in Jägersburg, Homburg, for Gustav, Duke of Zweibrücken

- 1720-1725 – Schloss Zweibrücken, a ducal palace for Gustav, Duke of Zweibrücken

- 1720-1730 – Hof- and Bergskirche Lutheran churches in Bad Bergzabern

- 1722 – the Edelhaus in Schwarzenacker, now part of the Römermuseum Schwarzenacker

- 1723 – Schloss Pettersheim, Herschweiler-Pettersheim, a hunting lodge for Gustav, Duke of Zweibrücken

- 1723 – a church in Niederkirchen

- 1723 – a church in Rathskirchen

- 1723 – the Schwedenhof in Einöd for Gustav, Duke of Zweibrücken

- 1723 – Bergzabern Palace for Gustav, Duke of Zweibrücken

- 1725-1731 – Schloss Gutenbrunnen, Wörschweiler, Homburg, for Gustav, Duke of Zweibrücken

- 1747 – the library (German: Archivgebäude) at Schloss Zweibrücken

- 1750-1756 – Evangelical Church in Birkenfeld (with Johannes Seiz)

- 1755 – Schloss Blieskastel, Blieskastel

- 1755 – Zwinglikirche, a church in Niederauerbach

Gallery

Part of Lustschloss Tschifflik (1715-1716)

Part of Lustschloss Tschifflik (1715-1716) Château Barrabino, Forbach (1716)

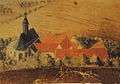

Château Barrabino, Forbach (1716) An 18th century view of Gräfinthal Abbey which includes the church built by Sundahl (1719)

An 18th century view of Gräfinthal Abbey which includes the church built by Sundahl (1719) Gustavsburg (1720)

Gustavsburg (1720) Schloss Zweibrücken (1720-1725)

Schloss Zweibrücken (1720-1725) Bergkirche, Bergzabern (1720-1730)

Bergkirche, Bergzabern (1720-1730) Schwarzenacker Edelhaus (1722)

Schwarzenacker Edelhaus (1722) Bergzabern Palace (1723)

Bergzabern Palace (1723) Schloss Pettersheim (1723)

Schloss Pettersheim (1723) Schwedenhof, Einöd (1723)

Schwedenhof, Einöd (1723) Schloss Gutenbrunnen (1725-1731)

Schloss Gutenbrunnen (1725-1731) Birkenfeld Evangelical Church (1750-1756)

Birkenfeld Evangelical Church (1750-1756) The orangery at Blieskastel (1755)

The orangery at Blieskastel (1755) Zwinglikirche, Niederauerbach (1755)

Zwinglikirche, Niederauerbach (1755)

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jonas Erikson Sundahl. |

- It is uncertain whether Oxenstierna asked simply for an architect, or for Sundahl by name.

- "Tschifflik" is a germanisation of the Turkish word "çiftlik", which means "farm".

- Lustschloss Tschifflik was a very early example in Germany of the "English garden" style.

- It is not impossible that Sundahl's architectural works between 1718 and 1724 or 1725, presumably authorised by Duke Gustav, were beginning to put a strain on the ducal finances.

- The facts that his employer Duke Gustav had died in 1731, and had been succeeded by Duke Christian that same year, may perhaps be relevant.

References

- Kneschke, Ernst Heinrich (1870). Neues allgemeines deutsches Adels-Lexicon (in German). 9. p. 114.

- "Sundahl Jonas Erikson". saarland-biografien.de (in German). Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- "Pfalz-Zweibrücken". barockstrasse-saarpfalz.de (in German). Retrieved 9 September 2017.

Other sources

- Edestam, Anders (1954). Jonas Erickson Sundahl. Gåserudspojken, som blev konstnär och hovman (in Swedish). By Anders Edestam.

- Lohmeyer, Karl (1957). Das barocke Zweibrücken und seine Meister (in German). pp. 11–28. ASIN B0000BPYZ3. By Karl Lohmeyer.