John Richardson (judge)

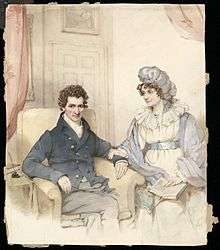

Sir John Richardson (1771–1841) was an English lawyer and judge.

Life

The third son of Anthony Richardson, a merchant of London, he was born in Copthall Court, Lothbury, on 3 March 1771. He was educated at Harrow School, and matriculated at University College, Oxford on 26 January 1789, graduated B.A. in 1792, taking the same year the Latin verse prize (on the subject Mary Queen of Scots), and proceeded M.A. in 1795. He was admitted in June 1793 a student at Lincoln's Inn. In early life Richardson was closely associated with William Stevens, by whom he was supported while at college. They both worked for the repeal of the penal laws against the Scottish episcopal church. Richardson was an original member of "Nobody's Club".[1]

After practising for some years as a special pleader, Richardson was called to the bar in June 1803. He was counsel for William Cobbett on his trial, 24 May 1804, for printing and publishing libels on the lord-lieutenant of Ireland and other officials, which were in the form of letters signed "Juverna";[2] and also in the concurrent civil action of a similar nature brought against him by William Plunket, 1st Baron Plunket, the Solicitor General for Ireland. Richardson acted for Cobbett with William Adam.[3] The author of the libel on the Irish officials was an Irish judge, Robert Johnson, justice of the Court of Common Pleas (Ireland); and when he was indicted at Westminster in June of the following year Richardson argued a plea to the jurisdiction, namely that, notwithstanding the Acts of Union 1800, the court of king's bench had no cognisance of offences done by Irishmen in Ireland. The plea was disallowed, Richardson appeared for Johnson in the trial which followed, and the matter ended in a nolle prosequi. About the same time he converting the defence of Henry Delahay Symonds on his trial for libelling John Thomas Troy, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Dublin, into an attack on Catholicism. Not long afterwards he was chosen to fill the post of "devil" to the attorney-general.[1]

In 1818 Richardson succeeded Sir Robert Dallas as puisne judge of the court of common pleas, also being made serjeant-at-law. On 3 June 1819 he was knighted by the Prince Regent at Carlton House. His tenure of office was curtailed when poor health compelled his retirement in May 1824.[1]

Much of Richardson's later life was spent in Malta, where he edited The Harlequin, or Anglo-Maltese Miscellany, and drafted a code of laws for the island. He died at his house in Bedford Square, London, on 19 March 1841. Richardson had married Harriet Hudson in 1804 in Wanlip. She was the daughter of Charles Grave Hudson, 1st Baronet.[4] They had five children. Joseph John (1807-1842), who was called to the bar at Lincoln's Inn in 1832, Anthony (1808-1829), Sarah Harriet (1809-1907), who married George Augustus Selwyn in 1839, Charles George (1810–1859) and William Stevens (1815-1861). His wife died in 1839.[1]

Notes

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1891). . Dictionary of National Biography. 28. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- John Selby Watson (1870). Biographies of John Wilkes and William Cobbett. W. Blackwood. p. 245. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- Richard Ingrams (25 October 2012). The Life and Adventures of William Cobbett (Text Only). HarperCollins Publishers. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-00-738926-1. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- The Scots Magazine, Vol 66, 1804

- Attribution

![]()