John Kinzie

John Kinzie (December 23, 1763 – June 6, 1828) was a fur trader from Quebec who first operated in Detroit and what became the Northwest Territory of the United States. A partner of William Burnett from Canada, about 1802-1803 Kinzie moved with his wife and child to Chicago, where they were among the first permanent European settlers. Kinzie Street (400N) in Chicago is named for him.[2] Their daughter Ellen Marion Kinzie, born in 1805, was believed to be the first child of European descent born in the settlement.

John Kinzie | |

|---|---|

| Born | December 23, 1763 |

| Died | June 6, 1828 (aged 64) |

| Resting place | Graceland Cemetery |

| Known for | First permanent European settler in Chicago |

| Spouse(s) | Margaret McKinzie Eleanor Lytle McKillip Kinzie |

| Children | John H. Kinzie, Ellen Marion Kinzie, Maria Kinzie, Robert Allen Kinzie |

In 1812 Kinzie killed Jean La Lime, who worked as an interpreter at Fort Dearborn in Chicago. This was known as "the first murder in Chicago".[3]

During the War of 1812, when living in Detroit, Kinzie was accused of treason by the British and imprisoned on a ship for transport to Great Britain. After escaping, he returned to American territory, settling again in Chicago by 1816. He lived there the rest of his years.

Early life and first family

Kinzie was born in Quebec City, Canada (then in the Colonial Province of Quebec) to John and Anne McKenzie, Scots-Irish immigrants. His father died before Kinzie was a year old, and his mother remarried. In 1773, the boy was apprenticed to George Farnham, a silversmith. Some of the jewelry created by Kinzie has been found in archaeological digs in Ohio.

By 1777, Kinzie had become a trader in Detroit, where he worked for William Burnett. As a trader, he became familiar with local Native American peoples and likely learned the dominant language. He developed trading at the Kekionga, a center of the Miami people.

In 1785, Kinzie helped rescue two American citizens, sisters, who had been kidnapped in 1775 from Virginia by the Shawnee and adopted into the tribe. One of the girls, Margaret McKinzie, married him;[4] her sister Elizabeth married his companion Clark. Margaret lived with Kinzie in Detroit and had three children with him. After several years, she left Kinzie and Detroit, and returned to Virginia with their children. All three of the Kinzie children eventually moved as adults to Chicago.

In 1789, Kinzie lost his business in the Kekionga (modern Fort Wayne, Indiana) and had to move further from the western U.S. frontier. The US was excluding Canadians from trade with the Native Americans in their territory. As the United States settlers continued to populate its western territory, Kinzie moved further west.

Marriage and move to Chicago

On March 10, 1798, Kinzie married again, to Eleanor Lytle McKillip. By the time they moved to Chicago, about 1802–1804, they had a year-old son, John. Eleanor bore him three more children in Chicago: Ellen Marion (born in 1805), Maria Indiana (1807), and Robert Allen (1810).

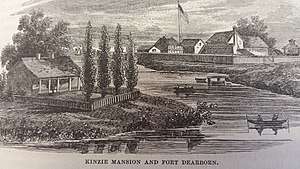

In 1804 Kinzie purchased the former house and lands of Jean Baptiste Point du Sable,[5] located near the mouth of the Chicago River. That same year, Governor William Henry Harrison of the Indiana Territory appointed Kinzie as a justice of the peace.

War of 1812

After American citizens built Fort Dearborn, Kinzie's influence and reputation rose in the area; he was useful because of his relationship with the Native Americans. The War of 1812 began between Great Britain and the United States, and tensions rose on the northern frontier.

In June 1812, Kinzie killed Jean La Lime, who worked as an interpreter at Fort Dearborn. He fled to Milwaukee, then in Indian territory.[6] While in Milwaukee, he met with pro-British Indians who were planning attacks on American settlements, including Chicago. Historians speculate that La Lime may have been informing on corruption related to purchasing supplies within the fort and been silenced. The case has been called "Chicago's first murder." [3] It has been also proposed the Kinzie's attempted to cover up the families early real estate transactions, substituting Francis May as the original owner (who died after eating at the son's [James] home).

Although worried that Chicago would be on heightened alert, a force of as many as 500 Indians attacked the small garrison of soldiers, their support and their families near the current intersection of 18th and Calumet, as they fled south along the lake shore after evacuated the Fort. The Fort Dearborn attack took place on August 15, 1812 and left 53 dead, including women and children. Kinzie and his family, aided by Potawatomi Indians led by Billy Caldwell, escaped unharmed and returned to Detroit.[7] Identifying as a British subject, Kinzie had a strong anti-American streak.

In 1813, the British arrested Kinzie and Jean Baptiste Chardonnai, also then living in Detroit, charging them with treason. They were accused of having corresponded with the enemy (the American General Harrison's army) while supplying gunpowder to chief Tecumseh's Indian forces, who were fighting alongside the British. Chardonnai escaped, but Kinzie was imprisoned on a ship for transport to England. When the ship put into port in Nova Scotia to weather a storm, Kinzie escaped. He returned to American-held Detroit by 1814.

Although he had previously been a British subject, Kinzie switched to the United States. He returned to Chicago with his family in 1816 and lived there until his death in 1828.

During the 1820s, Kinzie served as a justice of the peace for the newly created Pike County,[8]:254 which at the time extended from the Mississippi River to Lake Michigan.[8]:248

Death and legacy

Kinzie suffered a stroke on June 6, 1828 and died a few hours later. Originally buried at the Fort Dearborn Cemetery, Kinzie's remains were moved to City Cemetery in 1835. When the cemetery was closed due to concerns it could contaminate the city's water supply, Kinzie's remains were moved to Graceland Cemetery.

- In 1837, Kinzie's son John H. Kinzie ran for the position of the first mayor of Chicago, losing to William Butler Ogden. He subsequently unsuccessful ran twice more, in 1845 and in 1847.

- Maria Kinzie, a granddaughter, married George H. Steuart, a captain in the US cavalry from Maryland. He later served as a general in the Confederate Army.[9]

- His great-granddaughter, Juliette Gordon Low, was the founder of the Girl Scouts of the USA.

References

- Lossing, Benson (1868). The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. Harper & Brothers, Publishers. p. 303.

- Hayner, Don; McNamee, Tom (1988). Streetwise Chicago: a history of Chicago street names. Loyola University Press. p. 67. ISBN 0-8294-0597-6.

- "Chicago's First Murder," Chicago Daily Tribune, 27 November 1942, p. 10

- Eckert, Allan W. (March 1993) [First published 1992]. "Amplification Notes". A Sorrow In Our Heart: The Life of Tecumseh. United States: Bantam Books. pp. 886. ISBN 0-553-56174-X.

- Quaife, Milo Milton (June 1928). "Property of Jean Baptiste Point Sable". The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 15 (1): 89–96. JSTOR 1891669.

- Pierce, Bessie Louise (1937). A History of Chicago, Vol. I: The Beginning of a City 1673-1848. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 21.

- http://www.earlychicago.com/chron.php

- History of Pike County Illinois. Chicago: Chapman, 1880.

- Steuart, William Calvert, "The Steuart Hill Area's Colorful Past," Baltimore Sun, Sunday Sun Magazine, 10 February 1963

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Kinzie. |