John Harrison Mills

John Harrison Mills (January 11, 1842 - October 23, 1916) was born and died in western New York state, United States. He was raised on a farm but was on to start his art career into Buffalo, New York, just as the American Civil War came on, which he barely survived, advanced his writing and art career including with the rising Mark Twain, extended it further while living in Colorado published in national magazines with his growing family and his art was sold as well as kept in collections like at the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum and advanced the success of the business of art. Then back to New York where he again organized the business of art and then back to Buffalo where he continued his art and added to the Albright Gallery collection, as it was known then, and casting bronze works. As he settled into his last decade still producing art which was collected he also began to advocate for and established the first Bahá'í community of Buffalo, and was able to host ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, then head of the religion, during his journeys to the West in 1912 and Mills 50th anniversary recovering from the war, several other Bahá'ís, and continued on in all these endeavors of art and religion onto his unexpected death a little after his 50th wedding anniversary.

Biography

Born and raised

John Harrison Mills was first born son in the hamlet of Bowmansville, New York,[1] east out of Buffalo, January 11, 1842, of Aaron P. Mills[2] and Abigail near Lancaster, Erie County, New York. They were a farmer family and both parents were from Otsego. Soon he had two brothers, Daniel W. and a sister Elvira,[3] and a brother Aaron T. born about 1852.[4][5] All the children worked on the farm.[6]:p1 The Mills family in the area,[7] in the later 19th century had traced the family back to England circa 1630, and coming to Jamaica, Long Island, later part of Queens.[8] It was said that a great-grandfather of Mills was one of the first of seven settlers in Oswego County.[9] Mills later went to South Columbia, New York, seeking the gravesite of a grandfather, a Baptist preacher, and found a grave with the broken headstone of Daniel Mills who had died April 11, 1813, at 43 years of age on the then Hazelton farm west of town.[10] Daniel was son of Nathaniel Mills.[11]

Mills was known to mold clay turned up from the plow into recognizable forms.[2] Early biographer Benedict R. Maryniak said: “Long before he could read and write to a teacher’s satisfaction, (he) would return from the field and use charred wood to scratch out pictures of things he’d seen. Clay turned up by his plow would be molded info figures of barnyard animals.… people instantly recognized the things he had shaped and sketched.”[6]:p3 He was raised in a Baptist sensibility of serious mindedness.[6]:p3

Mother Abigail had died by late 1855.[12] In 1857 at age 15 Mills moved to Buffalo and undertook a life as an artist but Maryniak believed father Aaron must have endorsed the work as a step towards developing business sense.[6]:p3 First he was an apprentice bank-note engraver to Jack Jamison.[6]:p3 Mills suffered eye strain doing the work however and took up marble work with sculptor William Lautz and painting with Lars Gustav Sellstedt and, with encouragement from William H. Beard, began doing portraits.[6]:p3[13] At age 17, about 1859, Mills painted a portrait of his father.[2][6]:p3 He camped along the Niagara River 1859-1860 and sold paintings.[6]:pp3,79 That year in the fall he was noted as a member of the Nameless Club and had given a talk.[14] He was not living with the family on the farm at the 1860 Census, though he had a new younger half-brother named Charles and his father a new wife.[15] Mills had rented rooms for a studio in Buffalo by December,[16] in the vicinity where decades later Grover Cleveland lived near Main St and Swan St. in what was the Weed Block building.[17] In about 1861 two artists made a bust of Mills that he kept track of into 1872.[18]

Civil War

Mills signed up for the Union side in the Civil War after the April 12-13, 1861, Battle of Fort Sumter. [2] appearing on a roll on the 16th.[19] He was 19 years old.[20]:p354 What was hoped for of a war to be won in a matter of weeks took years.[6]:p5 The 21st New York Volunteer Infantry, uniformly called the 21st Regiment of New York at the time, began to be organized, reported to Elmira, New York, and "mustered out" May 8,[6]:p5 making their way to Washington, DC, where they joined the Army of the Potomac for the duration of the war,[21] by May 21,[2] there establishing “Camp Buffalo” and then “Fort Buffalo”.[6]:p5 He began the record keeping of the regiment in the early days of their deployment.[6]:p5 He also painted some portraits of soldiers and camps.[6]:p84 Soon they were marched down to and engaged the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861.[2] Mills was a private of Company D.[22][23]

He next fought on August 30, 1862, in the Second Battle of Bull Run and he recorded personal details of the battle in the Chronicles.[24]

_(14576024500).jpg)

He pointed out bodies that had been killed by bayonets and occasional bullet balls struck nearby trees.[25] He witnessed someone shot, and then saw General John Porter Hatch order the advance. “Fix Bayonets!” was called out. Then a tense moment crossing a road. He described the line of advancing soldiers as “… we feel the pounding breath of batteries, grape and canister sweep broad gaps in our little line, and it melts like the first snow of winter before this awful wind of bullets.” His company made it to the front line, advanced down a slope and began to engage in hand-to-hand combat. That is when he was struck down feeling nearly torn in two. He saw the clouds of smoke and heard the calls of the colonel amidst others dead and dying. He heard the order to fall back called out.[26] He crawled out of the ditch towards the rear and was picked up by two soldiers. Some grape exploded and they all dropped. They reached the road they had crossed when the adjunct of the 14th Brooklyn came through and an unknown soldier held him up and they moved past woods, Union batteries, storehouse, and he was shoved into an ambulance. He recalled it as a 10 minute wait before a full retreat was called and on his elbow he saw the sun setting and the Confederacy setting up where they had been. Onward went the ambulance and he went away from the battle.[26] He was listed as wounded back in Buffalo a few days later.[27] One report is that his leg had been shattered,[1] and Mills called it a knee injury his years to come, but it was a bullet lodged through the front to the back of his pelvis and had to be removed from the back side.[6]:p48 “They cut where I told them and when they pulled it out the suction made a noise… a sort of whistle that I will never forget.”[6]:p48 A captain of Company B came through his hospital in Alexandria[28] and noticed him among the wounded.[29] Some reports were that he nearly died and he gained a title “the name who would not die”.[2] He was registered as totally disabled.[20]:p354

Mills spent four months recovering and made some drawings which he sold on return to Buffalo.[6]:p48 While he was convalescing he began the work that led to the Chronicles of the 21st Regiment.[30] He also visited the old Smithsonian Institution during the time and saw George Catlin’s Indian and war paintings from before 1841.[31][6]:p48

Mills was discharged December 22, 1862,[20]:p354 and filed paperwork for his military pension, marked as an invalid.[32] Ultimately the regiment lost 2 officers and 74 enlisted men killed and mortally wounded plus 2 officers and 40 enlisted men lost to disease, for a total 118 lost.[21]

Buffalo

The first edition of Chronicles of the 21st Regiment of New York was produced in parts starting August, 1863.[33] He was advertising for more contributions to the history in late August with a contact address in town.[34] Another edition came out in later September.[35] His injury flared up,[36] and the 4th part was delayed to December.[37] Part 5 of the Chronicles came out the next year after a further serious illness,[38] and the last of the series came out in July 1866.[39] Amidst this work the New York State Agricultural Society gave him a bronze medal for a painting of a bull in 1864.[6]:p49

The next event commented on is when the Funeral and burial of Abraham Lincoln train came to Buffalo April 27, 1865. Mills was one of the honor guard for the coffin in St. James Hall.[1] "I cannot remember how it came to pass that I was chosen to stand guard at the head of our beloved President Lincoln on that momentous day…. I had been through so much in the past four years, two of which were spent amid battle, murder, and sudden death, that details did not lodge in my memory, whereas events, made indelible impressions…. Being on one crutch, I naturally could not march in the parade with the veterans of the 21st, 100th, and 49th, but I was early at St. James Hall, where a canopy and dais were being finished for the reception of the precious dead. I keenly remember an opening being made out on to Washington Street, and that over the sidewalk from Eagle Street south an incline was built to a platform over the basement windows, which admitted four abreast. After the procession the body was brought in from Main Street at 8 o'clock, and from that time up to 10 o'clock, when the crowd of men poured in from Washington Street, and of ladies & children from Main Street, I was at liberty to sketch the beloved face, so calm in death.… After my return from the war I plunged into both artistic and literary occupations, and my hair was worn long in the fashion of all artists of that period. As I stood at the head of the coffin in my faded soldier suit and fatigue cap, with my gun on my shoulder and my crutch against a pillar, looking neither to right or left, I heard a whispered, 'Mills, you ought to have got your hair cut. You don't look like a soldier.' I shall never forget the sensation made upon me, who had been for hours in the seventh heaven, as this mundane suggestion was directed at me from my friend George Gibson, also a long-haired artist. I landed on earth again, and after that was keenly alive to the eager mass of humanity which surged past the immortal dead up to 8 o'clock that evening, when the lying in state was over and the honors paid by Buffalo to the Nation's martyred president had passed into history.”[1]

He made a bust of Lincoln.[10] He later said it was made of plaster about ten inches tall and there were some copies made that were then tinted gray,[18] which were mass reproduced in the fall of 1865.[6]:p49 Mills was described by the president of the Buffalo Nameless Club in 1865 as “equally at home in sculpture, poesy, and painting. His bust of Abraham Lincoln, his poem of 'Booths', and twin pictures 'A dream of life' each are master pieces of conception and composition."[40]

Mills married Henrietta Fell August 25, 1865.[30] Henrietta was born April 26, 1845, in Chippewa, Canada, to James Wilkins Fell and Eliza A. Stoffman, both from Ontario.[41] The Mills' first child, son Harry/Harrison Winthrop, was born about 1867, followed by daughter Maggie/Margaret Elvira born about a year later.[42][6]:p49 Amidst these early days of their family Mills sketched scenes of a railroad disaster in 1867, the Angola Horror, for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper entitled “Viewing the remains of the victims of the Angola Disaster for Identification, at the Soldier’s Rest, Buffalo" published January, 1868.[43][44] Another daughter Bertha was born in 1869 but died after a few months.[6]:p49 In 1870 the couple and their two children were living in Buffalo in the home of Millsʻ wife's parents. Her father was a civil engineer and Mills was listed as an oil painter.[45] Henrietta was ill.[26] The rest of the Mills family - retired farmer Aaron, new wife Harriet, Alvira and David W.(possibly Daniel) full siblings and half sibling Charles - had moved to Rockford, Michigan,[46] where sister Elvira died in 1871,[47] and father Aaron had died in 1872.

Mills had entered into a partnership for a lithography business in 1869,[48] and a sketch of a policeman with “brawling" kids was well received.[49] From 1869 to 1872 Mills was also on the staff of the Buffalo Morning Express noteworthy especially because the chief editor of the paper was soon Samuel Clemens,[26][13] already known as Mark Twain, soon to be married, through the time of the death of son Langdon. Mills started as a copy reader for the newspaper and rose to be an assistant editor under Twain.[6]:p50 When Twain joined the paper Mills was responsible for converting drawings into wood-stock for printing.[50]:p49 Mills reworked Twain’s illustrations for a Buffalo Express series of articles spoofing coverage of a tightrope walker crossing of the Niagara Falls across later August into September 1869.[50]:pp69,213–9 During this time he and Clemens were both members of the "Nameless Club" of veterans of war from before and after the Civil War though it did not long continue.[51][6]:p50 Mills recalls himself and Twain the club in a later write-up - it was an loose association with women and men were in the club though it did hold elections sometimes,(the last Mills recalled was in 1863,) and the group sometimes went down to the beach.[52] Instead of that club of veterans, by that December, Mills was an elected senior Vice Commander of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) of Post Chaplin in Buffalo.[53] Mills did a portrait of Twain in 1870 which was reportedly in the household of a descendent in Chicago as of 2013.[50]:pp166,305[6]:p50[26]

By then Henrietta's health meant they had to move[26] to a drier climate.[6]:p57 Perhaps in part influenced by George Catlin's art,[31] the couple decided to move to Colorado.[31] He had sold paintings in Buffalo before going west along with drawings of the Niagara River and of the war.[31] Some art of Mills was included in an exhibit - a painting entitled “Come On” - on June 17, 1872.[54] He was packing to move by late June[55] and remarked upon as having left the first week of July.[56] He left the mold for the bust of Lincoln at his studio in a building in town along with one of himself intending to send for them - he never saw them again.[18]

Colorado

They arrived in Colorado[6]:p1 riding the Union Pacific Railroad.[31] He had a brother, Aaron T. Mills,[5][57] there who had an engraving company which advertised a good deal in all the newspapers and commented on in the Rocky Mountain News in January 1872.[58] By October Mills took a prize at the Art Department of Colorado's Agricultural Fair.[58] He had bought 5 acres of land in town.[6]:p57

In January 1873 Mills penned a poem published back east about the expanding of America into the West and the changes wrought of the year 1871, fallen soldiers and chased peoples,[59] and published in the Rocky Mountain News in Denver,[58] which begins:

The Chronicler, as you may see,

To sadness is inclined.

And, certes, in this History

The reason you may find.

For it relates the noble deeds

So well and bravely done

By him we mourn; his headstone

reads:

Here lieth Seventy One

He did a painting of a celebrated grade sheep for the stockmen's show in late January as noted in the Denver Times.[58] Mills was joined by the Buffalo artist Hamilton Hamilton,[60] and together they sold art during the year.[61] They went on the Upper Arkansas expedition invited by the Chain & Hardy Bookshop owners kin to painter Helen Henderson Chain.[6]:p79 Mills took other horse trips into the mountains and did water colors and then took up an office in Denver where he offered classes like to Alexander Phimister Proctor by 1873.[62][63]

It was recalled years later that it was perhaps a test of their patience to work together each and Mills took him on trips into the mountains to see nature first hand.[31][64] Mills' painting of “Boulder Falls” was purchased in June, 1873,[58] and a work was used in the heading in the new paper, the Sunday Morning Mirror as well.[58] In October Mills contributed to an article in Frank Leslie's Weekly entitled "Life and scenes in Denver, Colorado",[65] and then another "A street scene - buying outfits for the mountains and the mines".[66] It was reported he returned from a trip into the mountains, where he has been sketching, in early October.[58]

Mills exhibited his oil painting of bishop George M. Randall, copied from a photo, in early May 1874.[58] As his wife’s health improved they bought a wagon and began to meander the lands, first visiting an old Bowmansville schoolmate and then on to further voyages.[64] They made a trip to the Colorado Basin, called "Middle Park", far to the north west of Denver, near Longs Peak, found a place to make a homestead.[64] Circa 1874 they were living in what was then called Hot Sulphur Springs, just organized as the county seat of Grand County, Colorado, and where Henrietta’s school was remembered decades later.[67][68] The school was partly paid for by the family themselves.[6]:p58 A dozen children were taught reading, writing, and math.[6]:p58 Late in life Henrietta told stories of Ute Chief Colorow visiting her school often and sometimes climbing onto the table and cry out “All Utes! All Utes! White man must go!” amidst the lessons of the class.[6]:p58

Mills had a short narrative published back east late 1874 "Indian Summer" about days in October,[69] which was soon followed by a poem “Over the Range" at the end of December,[70] which was soon widely echoed in the opening of 1875.[71][58]

Half sleeping, by the fire I sit,

I start, and wake, it is so strange

To find myself alone, and Tom

Across the Range.

We brought him in with heavy feet

And eased him down; from eye to eye

Though no one spoke, there passed a fear

That Tom must die.

He rallied when the sun was low,

And spoke, I thought the words were strange,

"It's almost night, and I must go

Across the Range."

"What, Tom?" he smile and nodded, "Yes

They've struck it rich there, Jim, you know

The parson told us; you'll come soon :–

Now Tom must go."

I brought his sweetheart's picture face,

Again, that smile, so sad and strange.

"Tell her," he said, "that Tom has gone

Across the Range."

The last light lingered on the hill.

"There's a Pass, somewhere," then he said,

And lip, and eye, and head were still,

And Tom was dead.

Half sleeping, by the fire I sit,

I start and wake, it is so strange

To find myself alone, and Tom

Meanwhile his two paintings, “East on the So. Boulder” and “West on the Grand” were mentioned in January and February 1875 in Denver newspapers.[58] In March[72] portrait work of Mills in Denver was recalled in Buffalo and in June other poems were published too.[73] Sometime during his time in Colorado Mills painting "Artist Painting a Satirical Painting" was undertaken and finished.[74]

Before moving back to Denver permanently Mills once suffered from rheumatic fever and had to be rescued by hunters and carried several miles through snow.[6]:p57 The scenes were rich topics of art but barren of purchasers of paintings and it was a hard life.[6]:p60

The family moved back to Denver in 1876 into a brick house and a studio at what grew to become the Tabor Grand Opera House.[6]:p51 In Denver Mills organized art schools and associations though they didn’t survive long.[61] Mills was known working on the "School in the Middle Park" (with similar titles like "Dugout Cabin Home School"[6]:p60) painting in April and Mills was also appointed a probate judge,[75] though sometimes called a lawyer later[6]:p51 seemingly partly on a reputation of mediating differences between whites and Ute people.[64] Mills painting "First School in Middle Park" was advanced by early September along with another painting of a herd of elk - and it was noted in the newspaper that he was secretary of the local republican party.[76] The painting was of Henrietta teaching children in their home with an Indian, perhaps Ute Chief Colorow in the background in the woods outside.[68] In October Mills did some art for The Century Magazine entitled “Hunting the Mule Deer” which was echoed, if credit was cut.[64] Engraving was his success in these times. There is a photograph of Mills in the Denver Public Library Western History Department from circa 1876.[6]:p90

More art of Mills was noted in 1877 - in March Mills had artwork of snowshoeing published,[77][78][6]:pp92–104 a cartoon of a public figure in May,[58] and went to what is now the Old La Veta Pass to sketch in later July.[58]

Mills opened a studio room in the Academy Building and advertised for students in June 2, 1878,[58] and painted “Through fire and flood" which was auctioned in July.[79] Mills sent wood engravings to Scribner’s Monthly uninvited which they then turned around into a commission.[6]:p84 Mills sold art and writing to them and Harper's Magazine.[64] In particular a 12 page article in Scribner’s Monthly with mostly his own sketches with the story "Hunting the Mule-Deer in Colorado" was published in September.[80]

In February 1879 Mills was co-owner of a publishing shop in Denver.[81] In March there was comment on Mills writing in Canada,[82] and then a Denver News edition published an engraving by Mills.[83] A journalist had visited the Mills home in Middle park and left an article that was published in May,[84] his poem "Across the range" was published again,[85] and there was comment that Mills anticipated finishing an oil portrait of a Denverite in late August.[58] Mills also had another article in Scribner Magazine with 12 illustrations under “The Camp of the Carbonates,” for the October edition.[58][86]

Mills contributed a long poem at the beginning of the 1880 published in History of Clear Creek and Boulder Valleys,[87] and another “Colorado,” was published in 1880 in a newspaper.[58] The Mills family, with Harry and Maggie, lived in Denver with three young male boarders at what was then 286 Seventh St. with Mills listed as a landscape painter.[42] Mills was commissioned by George Crofutt to do illustrations and wood-engravings for guidebooks including “Chicago Lakes, below Towering Mount Evans”, and in 1881 did “Colorado Springs, Pike’s Peak Sunset”, called his greatest wood-engraving, and also “Nearing Kenosha Hill, Union Pacific Railway” and “South Park from Kenosha Hill”.[6]:pp69–73 The engraving/publishing company Mills was a partner in expanded in 1881.[88] He passed through Buffalo to New York in February.[89] Henrietta was a member of the Executive Committee Emmanuel Hospital Ladies Aid Society by April.[58] Mill's painting, “Frontier School House”, which was shown at the Mining Exposition in mid-April, and was alongside with a “Pencil and Brush” piece.[58]

In January 1882 Millsʼ painting “Frontier School" was reported sold at $1000 to Wolfe Londoner,[90] later Mayor of Denver. That would be more than $25,000 in 2020 dollars.[91] A description of the painting was posted in September while it was on display at the Art Gallery.[92] By 1939 the painting was reportedly owned by Mrs. John Zick of Grand Lake.[93] Mills did multiple “pioneer-life dugout” paintings including “News from Home” done in 1882 which is now in the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum.[6]:p75[94][13] Henrietta's health returned and she bore a third child - John Eghert - born June 19, 1882.[64] As president of the Academy of Fine Arts of Colorado Mills worked with state senator and mining tycoon Horace Tabor to set up an exhibitions in the summers of 1882 and 1883[95] called The Mining and Industrial Exposition.[96] Mills taught through the Academy as well[13] holding meetings in the Tabor Opera House building.[58] Though the date is uncertain, Albert Wilbur Steele was also a student of Mills.[97] One association Mills founded, the Colorado Academy of Design, suffered from conflicts between artists and business leaders. Despite the beginning and ending of groups, Mills had great influence in developing artists and an art market.[6]:pp61–2

In July 1883 Henrietta was a delegate from the Denver chapter of the Ladies Auxiliary to the national meeting.[98] The Woman's Relief Corps was established by the GAR at Farragut Post, chartered with Mills present.[99] Attempts at organizing a GAR women's association had been suggested back to 1879, escalated 1881, but at that July 25, 1883 meeting, existing Ladies Auxiliaries sent representatives to the Denver meeting met presided over by E. Florence Barker and secretary Kate Brownlee Sherwood which founded the Woman's Relief Corps. Henrietta was a charter member and founded the Colorado state chapter in her home in Denver, the first corps of the state, and was its first president,[99] the Farragut Relief Corps, by September.[100] In October Mills wrote an article reporting on the Farragut meeting on another point of organization. In it he examples a local militia troop that had formed including a direct reference to the authority of the US president in service to the constitution and the national government rather than to the state government and in a formal relationship with the GAR. He also mentions being part of a “crack corps" of the militia regiments of New York which he thought might have been the most organized of the civilian organizations and still far from ready for military service of the nation at need.[101] Millsʻ point of view in the article was responded to by declining a centralized organization under that of the national government in favor of being the exclusive right of the states and isn’t a responsibility of the GAR though such units per state should have a close relationship with the GAR.[102] In mid-December Mills aided the organization of the GAR corp in Delta, Colorado,[103] and in late December Mills was elected to the Farragut GAR corps as commander.[104]

The family had moved to Santa Fe Ave, Denver, and then to North Denver in the fall of 1885.[64] Two contracts came up to paint portraits of people in New York in 1885.[64] The family was on the Colorado state census of 1885 living in Arapahoe County; son Harry was a machinist.[105] In October Mills stayed with Buffalo kin on his way to New York again.[106]

In 1886 the Mills son Harry/Harrison married in Denver in July;[107] they had a child Elsworth later that year.[108] Meanwhile Henrietta and daughter Margaret joined Mills in New York.[64] Coverage of Mills in Buffalo was still catching up with him - noting his old studio in the Holbein Building, that he had been of the staff of the Buffalo Express and an old painting of his "Morgan Road" while also mentioning newer paintings in Colorado like his "Forgotton Martyrs", "the Captive", "Embarkation at the Street" and "His Father a Soldier".[109] His brother Aaron stayed in the Denver area until about 1890 before moving to San Antonio, Texas.[5]

New York city

In 1887 an edition of Mills' Chronicles was published by the regiment's Veteran Association.[20] Exhibits at the American Art Association in New York, such as in 1885,[110] and others,[111] spread Mills reputation and he was invited to the founding of New York Art Guild where he became “General manager” under the president and friend Thomas Moran.[6]:p84 By 1889 the American Fine Arts Society was incorporated in New York with Mills among the trustees - the organization had formed in order to purchase a building for shows and exhibitions.[112] Amidst these Mills was also in a GAR outing for their 10th anniversary with a harbor cruise with Mills among the organizers for, and riding on, the Barge John Neilson from 34th Street in mid-June 1888.[113] In 1890 two paintings and a statue were stolen from Mill's home from the office in his basement,[114] and he commented he was too busy for more than brief trips into the country for new inspiration.[115]

In March 1891 the New York Art Guild incorporated with Mills,[116] and in August he returned to Buffalo for a 21st Regiment reunion.[117] In 1892 Mills was coordinating the New York component of the country's contribution to the World of Art exhibition to be held in DC at the Smithsonian Institution which included Henrietta hosting a reception for the artists held at the White House,[118] and he also opened a shipping company for artists.[119] Mills also contributed a painting "On the Croquet Ground of Central Park" for fundraising for the Grant's Tomb in June.[120] Their son Harry/Harrison had joined them in Manhattan by April[121] after the birth of their second child/first daughter.[122] Mills was among the painters that exhibited at the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago,[123] as well as in a New York exhibition with a plaster bust,[124] and another with a painting.[125] In 1894 Mills was mentioned from New York at the incorporation of the Niagara Falls Park Bridge Company,[126] though it was blocked from forming.[127]

In 1895 things began to pick up alittle. Mills was advertising to take a group to a summer home in Rothesay, New Brunswick area with a deduction for art students.[128] That fall there was advertising for a school and exhibition series,[129] and the school began regular advertising in November on to February 1896.[130] In July Millsʻ Chronicles was remembered to readers in Buffalo in light of another history of another regiment,[131] then around the time of their son Harrison's second son born in August,[132] while Henrietta was on an extended visit at her brother's in Buffalo from August through to January, 1897,[133] probably helping to take care of her ailing mother who died in 1899.[134]

_detail%2C_3g04637u_unprocessed_(cropped).jpg)

She had managed send in a paper she had written to a New York Political Study Club which was read in her absence on the subject of the political history of Pennsylvania, the very state her husband had moved to briefly;[135][136] so long was it that it was read through two successive meetings.[137] The following May Henrietta was back in New York and found a dead teacher.[138] In August a bicyclist ran into Mills and broken an arm of his in the incident.[139] Henrietta's reputation of organizing the Woman's Relief Corp was picked up in New York.[140]

In March 1898 Mills was in an auction of his shipping company though overall sales were disappointing.[141] In April Mills artistsʼ packing and supply company continued business now with son H. Winthrop Mills.[142] Also in April Henrietta was among the executive committee seeking aid to soldiers through the just renamed Woman's National War Relief Association under Ellen Hardin Walworth in response to the Spanish–American War which brought in a Confederate organization into the association.[143] Following the previous work developing a group of exhibitions, it was this year Mills organized the "Art Kalendarium" exhibition series for the New York Art Guild.[144][10] At the time they were living in New York on E. 23 St.[145] Daughter Margaret married Charles Sprague in later June in Manhattan.[146] After the death of Henrietta's mother in January 1899,[134] she traveled visiting kin before returning back to New York city.[147] By June 1900 the Mills were living in a borough of Manhattan with only son John E. at home and a servant at what was then 18 E. 2nd St.[148] In March 1901 Henrietta's paper to the New York Political Study group was read in her absence.[149]

Westford

By April 1901 they had moved to Westford, New York, alittle west of Albany, where Henrietta had formed a branch of the Sunshine Society club.[150] The society was founded “to bring the sunshine of happiness to the greatest possible number of hearts and homes" and often served the blind.[151]

In the summer of 1902 Mills won the New York Herald’s prize for best poem on the 39th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg among 1000 submitted and judged by Edwin Markham, General Daniel E. Sickles, and George Cary Eggleston with second prize going to “The Charge of the Devil’s Den" which was submitted anonymously.[9][10] Mills poem "The Third Day" was widely echoed and then syndicated in lesser or more quotation.[152] It ends:

The little house would hold no more:

The little maid was not afraid,

But the tender eyes ran o'er;

The spent shot swept the town,

With the dying she lay down;

The little maid smiled - she was not afraid

The publicity of the poem and his win led to more profiles of him and further echoes - the prize for winning was $100,[68] (more than $2500 in 2020 dollars.)[91] Though it was not universally liked - a syndicated commentator didn’t like it[153] - nevertheless, it was increasing circulated: Massachusetts,[154] Kansas,[155] Missouri,[156] Oklahoma,[157] Iowa,[158] Nebraska,[159] Louisiana,[160] and Utah,[161] and was featured in the Memorial Day efforts of women in DC that year.[162] There was also a profile of Mills and two paintings published in the Denver Morning Post in July 27, 1902.[58]

By then Mills had been a member of the New York Water Color Club and another painting “His father was a soldier" was known in New York.[68] Son "Jack" had remodeled the Millsʻ studio in Westford using skills he was learning working at Tiffany.[68]

Buffalo

Coming to Buffalo

Mill’s son John E. was in a controversy over the disposition of some artwork in New York in March, 1903.[163] Meanwhile the Mills were soon living in Buffalo at 494 Elmwood Ave. and this would prove his final address for the last little more than a decade of life. The home had been for sale as early as 1889,[164] changed hands and was improved a number of times,[165] before finally being listed for rent into August, 1904,[166] before Mills family taking up as residence there in later October through his son "Jack".[167] The first sign of one major pattern of engagement of the Mills in this period of their life came in early December when the local society pages began to mention the Mills hosting meetings at their home.[168] They were also working on their own property improvements.[169] Their weekly informal meetings of friends continued in early 1905, some of whom were art exhibitions.[170] following which they reduced the number of meetings to one a week for a while.[171] Artist connection Charles Ward Rhodes came through in mid-April[172] and they were themselves guests at a reception with their friend.[173] They continued their regular meetings at the reduced rate of once a week, sometimes as a "Tea" for showing art.[174] Ward returned in later May again, associated with the dedication of the Albright Art Gallery,[175] what became later the Albright–Knox Art Gallery.

.jpg)

The date of this is unknown but Mills had gone to South Columbia, New York, seeking the gravesite of his grandfather, an early Baptist preacher and found a grave with the broken headstone of Daniel Mills.[10]

A profile of Mills was written in 1905 in the Artists Year Book out of Chicago.[135] Among a few details it noted he had exhibited at the National Academy of Design in New York, was a member of various professional arts clubs in New York including the Salmagundi Club, joined some Philadelphia arts clubs, and other locations, though the dates are largely unknown.

The New York State Census of 1905 finds the Mills in Buffalo with son John and a servant;[176] the Mills' other son Harry/Harrison was living in Manhattan with his family.[177]A new painting by Mills was showcased in a business window in town in July and they carried on hosting meetings and friends into the fall,[178] and working on more portraits.[179] A couple weeks later meetings at the Mills home resumed starting with a traveling artist Ammi Farnham.[180] General meetings at the Mills home continued in November,[181] while Henrietta also visited kin and friends,[182] and began her associations with clubs in Buffalo.[183] At the end of November Mills donated a painting he had done in 1884 to the art gallery,[184] and then Henrietta was listed among many attended an anti-suffragist meeting by Ida Tarbell,[185] followed by a pro-suffragist meeting[186] while mention of the Millsʼ meetings at their home continued along with home based exhibitions of paintings and visits of kin.[187] Mills also did a class on clay modeling.[188]

Founding the local Bahá'í communtiy and the Mills

Mills formally presented recent portraits at a reception in January 1906,[189] and Henrietta attended a class on French history.[190] The meetings the Mills hosted were noted in mid-January with a special guest coming[191] though it wasn’t said who.[192] January closed with Henrietta attending a mass meeting of women’s clubs,[193] and in February Mills joined in the founding of and was named a director for the Artists and Illustrators Club of Buffalo,[194] set an exhibition of his art students,[195] and in late February Mill’s poems "What they did to the flag" and the Gettysburg poem was asked for in the newspaper.[196] March opened with Henrietta attending a club who had merged with the Sunshine Society.[197] Later in March daughter Margaret came to town,[198] and a week later Mills finished a portrait of the youngest son of Seneca Chief Red Jacket.[199]

The first public mention of the Bahá'í Faith in the newspapers came in relation to the meetings at the Mill’s home. It was by their daughter Margaret, held approaching the period of the Bahá'í holy day of Ridván in a series of talks from April 19,[200] about the time meetings of the Bahá'ís were later credited beginning.[201][202] Mills later referenced his interest in the religion back to 1902 when he was living in New York city.[203] The religion had been mentioned in relation to visitors to Green Acre in 1902 in Buffalo, already a place Bahá'í scholar Mirza Abu Fadl was visible, and, as characterized by the visitor there, the whole situation was one of an emphasis on freedom of religious exploration and against the “spirit of commercialism".[204] Rev. Howard C. Ives had given a sermon there in early 1905[205] and would join the religion.[206] Another early mention of Bábí-Bahá'í history was also in a Buffalo newspaper in 1905.[207] However it seems none of this was known to the Mills - or at least not enough. They wanted to have more Bahá'ís around to work with. In November the Bahá'í House of Spirituality of Chicago, a precursor of the Bahá'í administrative institution the Local Assembly, wrote to Henrietta which scholar on the religion Robert Stockman summarized as: "We would love to help in Buffalo; but we don't know of any believers there."[208] Quite possibly the connection to the Mills with the religion was their son-in-law Charles Sprague. In 1900 Charles had already been an active Bahá'í in New York.[209] However by later 1905 Charles had moved to Philadelphia[210]:p215 and by early 1906 Margaret was now living in Buffalo.

The Mills attended a large reception of the Buffalo Society of Artists in late April,[211] and he exhibited some paintings of his.[212] In mid-May a followup Tea was held with Henrietta attending and further work by Mills for another exhibition.[213] After a couple weeks lapse of meetings, luncheons and exhibitions at the Mills home started again later in May.[214] Millsʻ daughter Margaret was set to speak at the Progressive Thought League of Buffalo, (the "League",) and showed a well-received painting “Spirit of the Storm" in June.[215] The League had been organized in January that year by Elizabeth Marney Conner and Grace Carew Sheldon.[216][217] Margaret was soon going to present a paper there with quotes of Bahá'uʻlláh.[218] The League report in the newspaper mentioned that when Margaret read her paper Bahá'í Margaret Peeke[219] commented from the audience that she had seen 'Abdu’l-Bahá, (following her 1899 pilgrimage,) then head of the religion. Daughter Margaret's paper was printed in the newspaper. It doesn’t have citations but mentions Mrs. Brittingham,[220] a book by Phelps,[221] and quotes from the Hidden Words of Bahá'u'lláh: “O Son of Man! My eternity is my creation and I have created it for thee…"[222]

A couple weeks later Mills’ poem "The Third Day" for the memorialization of the Battle of Gettysburg was published in Buffalo just before Independence Day.[223] A week later Margaret shared a letter from Bahá'ís on pilgrimage about prayer at the League meeting,[224] and by mid-July she was a vice president of the League and commenting on 'Abdu’l-Bahá.[225] The Mills were then away for two weeks to Ontario for a vacation,[226] immediately following which Bahá'í Alma Knobloch[227] was the guest of the Mills.[228] Knobloch initiated a protracted period of effort on behalf of the religion following the efforts of Margaret. In the regular report of the League in the newspaper there was a prayer of 'Abdu'l-Bahá's, via Knobloch speaking at the next meeting, and of Rev. M. K Schermerhorn speaking at other locations including Green Acre. The prayer begins “He is God. O unequaled Lord! For this helpless child be a protection. For this weak and sinful one be kind and forgiving. O Creator! Although we are but useless grass, still we are of Thy garden; though we are but young trees, bare of leaves and blossoms, still we are of Thy Orchard.…".[229] That next meeting went well,[230] and now in mid-August Knobloch gave a paper at another League meeting which was printed in the newspaper.[231] There were no citations but she refers to a previous compilation by Mrs. Boyle,[232] another separate meeting was scheduled, and that Bahá'í Joseph Hannen[227] was coming to give multiple talks. Hannen was Knobloch's brother in law and among their recent initiatives in DC were presentations to the black community of DC.[233] A few days later a notice of some guests from Ontario came to stay with the Mills in later August,[234] following which there was notice in the League report that Hannen gave his talk, that other Bahá'í meetings were scheduled, and Bahá'ís Mary Little,[235] Knobloch and Margaret were available for questions.[236] August closed with mention that Mills had an serious altercation with a dog.[237] Knobloch was at the next League meeting and spoke briefly about the religion,[238] and a week later the League congratulated Bahá'ís Sarah Farmer of Green Acre and Percy Woodcock on their work there and mentioned there were regular Bahá'í meetings on Sunday night at the League meeting room.[239] In mid-September son John married Winifred Harrington in a small private ceremony.[240] At the end of September the League reported it had had visitors from Chicago and New York recently and one had sent a copy of the Hidden Words.[241] The article closed with the quote of Bahá’u'lláh “Let not a man glory in this that he loves his country; let him rather glory in this that he loved his kindʻ (but misspelled Bahá’u'lláh as Baha Wullah.) Explicitly “Bahaei"(sic) meetings were scheduled at the League and, separately advertised, were noted as well at the Mills home.[242] A League meeting a week later quoted Bahá'í Howard MacNutt[243] and included a letter from ʻAbdu’l-Bahá in the newspaper coverage.[244] The letter starts “He is God, O ye spiritual assembly! As ye were gathered in the meeting of hospitality with the utmost love for the knowledge of God, that meeting was mentioned in the Divine Kingdom; and you became favored with special bounty. Such gatherings are very praiseworthy…" and was published separately by Bahá'ís as well.[245] There was another letter from 'Abdu'l-Bahá to the Bahá'ís in Buffalo[246] and in a third letter where 'Abdu'l-Bahá answered a letter from Margaret. She had written that she wished for martyrdom to which 'Abdu'l-Bahá replied: “This is the ultimate desire of the people of sanctity. If the eternal prosperity favor and befriend thee, thou wilt undoubtedly attain to this bounty. But for the present this very attitude is sacrifice and martyrdom. Blessed are thou, and again, blessed are thou!" dated October 17, 1906.[247] It had arrived a few days or more after Margaret had a night of hysteria of some kind at the Mills home and broke her arm in a midnight run from her parent’s house; she was sent to a state hospital,[248] now known as the Richardson Olmsted Complex. The next reports from the League meeting didn’t mention Margaret save to say she was still listed as a vice president; other Mills and Bahá'ís were not mentioned either.[249] In early-mid November Mills had some portrait work,[250] and kin visited with the Mills a week later.[251] In December 'Abdu'l-Bahá answered a letter from Henrietta with some sections.[252] It encouraged recognition of the work Knobloch and Margaret had been doing and mentioned their son Harry and his new wife Winifred. There was then another letter this time to Knobloch with many sections.[253] It encouraged her work and compared it to the early days of Christianity when there were so few believers. It said to show the "utmost affection and love toward Mrs. Sprague,"(Margaret) and for the Mills: “A most great gift is prepared and made ready for you in the universe of the Kingdom and the invisible realm. Display ye an endeavor and show ye an effort, so that ye may attain to it and become eternal and everlasting.” It also had a brief message to Grace Carew Sheldon, president of the League: "If thou art seeking a heavenly palace, make thy house the gathering-place of the friends of God" and further statements. Knobloch's many months of presence and activity in the community and subsequent returns are reminiscent of other examples of Bahá'í engagement in local activity.[254]

There is then reduced mention of activities. At the end of January the Mills were hosting a guest followed by an exhibition and reception at the Albright Gallery.[255] Across April the Sunshine Club met at the Mill’s home several times, and other times Henrietta was visible attending other meetings of the club.[256] But approaching mid-April Mills himself gave a talk “Bahais at home and abroad" to “hear about and understand the teachings of the Master, Baha Ullah(sic)".[257] This was about a year after his daughter's first public talks and six months after her breakdown. It was listed with the League calendar of events, though his daughter is no longer listed as an officer of the League. A couple weeks later Mills was part of the Society of Artists exhibition with some landscapes.[258] Whether a repeat or delayed by the exhibition, a talk of Mill’s for the League was advertised for May 7, 1907. It was entitled “Bahaism, it's mission as a unifier of all faiths".[259] There was also a presentation of the work of the Sunshine society at the same League meeting. Mills' talk was summarized the next day in larger or shorter reviews in a couple newspapers.[203] Mills described the religion having no churches, no clergy, no sacred orders, that he objected to the word "cult", that he had been interested in it some nine years already and that, though membership was not exclusive of other churches, there were some 35 people who he counted as the Buffalo Bahá'í community. He also outlined the history of the religion from the time of the Báb to Bahá’u’lláh to 'Abdu’l-Bahá. He closed saying the religion was the “cord which binds all faiths in God as One." Pastor Thomas French of the Church of Divine Humanity commended it and said he would investigate it further.[203] A few days later Henrietta was noted supporting a new chapter of the Sunshine Society over in Westover Alden.[260] Mills and Knobloch were mentioned in coverage of the League in a magazine though not stating their religion.[217]

Opening June Bahá'ís Percy and Mrs. Woodcock gave a talk at the Mills home on the religion; it was said Percy had been known to Mills over his lifetime and that he was expected to talk at Green Acres soon.[261] A few days later Mills held exhibitions of his paintings at their home,[262] and then it was noted Bahá'í literature could be obtained free from there.[263] In July Henrietta hosted the Chapin Women's Relief Corps,[264] and Mills was finishing some paintings for orders that had come in.[265] A week into August Joseph Hannen returned with his son staying at the Mills for a few days along with grandson Ellsworth S. Mills.[266] A week later Henrietta was a committee member of the reorganized chapter of the Sunshine Society and meeting,[267] and at GAR meetings into September.[268] Mills presented a medallion he made to the Sunshine Society in early September,[269] while Old Home Week events continued with Henrietta's involvement.[270] About then Mills joined the Buffalo Historical Society.[271][272]

About a month later the Mills were at a Sunshine Society meeting and Henrietta was elected a delegate to their state convention.[273] Approaching mid-November Henrietta hosted the local Sunshine club at their home,[274] and Mills attended an Albright Gallery showing and reception.[275] A notice then appeared that a social Tea Henrietta was having was delayed,[276] attended another Sunshine meeting[277] and over in New York son Harrison was one of the incorporators of the Bahá'í Spiritual Assembly of New York in later November.[278] A few days later Mills gave a talk on art for the League,[279] followed by an exhibition of his art at his home,[280] and Henrietta attended Sunshine Society season's festivals.[281]

January 1908 was a much busier month. It opened with the Mills hosting Bahá'í Charles Mason Remey recently back from his pilgrimage.[282] The next week Henrietta and Mills had further meetings and exhibitions,[283] and then they hosted the League’s business meeting for the new year during which Mills was listed as the vice-president.[284] Mills attended a Society of Artists meeting.[285]

In February Mills contributed some paintings to a new exhibition,[286] Henrietta was in Sunshine meetings as president,[287] hosting the Chapin Women's Relief Corps,[288] and then the Daughters of Veterans of the Civil War.[289] Mills finished a painting of Bahá'í 'Abdu’l-Karim who had visited America 1901-2, (see Lua Getsinger,) which Mills now put on exhibition.[290]

In May publicity came out that Mills poem would be part of a magazine,[291] and it was echoed,[292] while Henrietta was at a Sunshine Society meeting of presidents of chapters,[293] followed by hosting a meeting of her own.[294]

Another of Mills' poems was in the June issue of a magazine,[295] and similarly echoed.[296] In mid-July the Mills hosted son Harry and family.[297] following which Mills, still listed as a vice-president(vp) of the League, gave an extended talk on the religion and the paper was printed entitled “Basis of the Bahai Faith".[298] He mentions being a lay reader of the Episcopal Church for years and says: “The true Behai(sic) enters the Mosque, the Temple, the Synagogue, the Church - wherever men bow themselves in acknowledgement of the Unity which is God, there, if permitted, the Bahai bends or bows or kneels or prostrates himself in prayer. All creeds are his that say 'I believe in One Father' for that implies universal brotherhood" and after many more parts closes with reference to 'Abdu’l-Bahá. The next appearance of the Mills was in mid-August with Mills giving a talk “Should Fraternities Fraternize?"[299] Mills' talk on the religion affected an audience member who wrote a letter to the editor thinking on the topic of brotherhood[300] and Mills continued to be listed as vp.[301]

A magazine was advertised in which Mills did the portraits of some men.[302] In November the League posted a memorial for Peeke who had died and with note of her pilgrimage,[303] and then the Mills advertised a Bahá'í meeting in their home.[304] By around November Bahá'í Adolph Dahl and family had moved to Buffalo though by spring 1909 the famiy was listed from Pittsburgh.[210]:pp215,462–3,483 Henrietta was again elected a delegate of the Sunshine Society and Mills was painting and showings.[305] Henrietta aided a Sunshine Society event,[306] and Mills was still vp of the League.[307] The Mills were then away visiting that winter to Fort Erie.[308] They returned in short order for the January 1909 opening meeting of the League with Mills commenting briefly of international developments; the spreading of self-government in the east, and that struggles in the world represented working out of problems that we may not recognize.[309] Meanwhile his poem Uplift was reprinted,[310] and Henrietta was elected president of the local chapter of the Sunshine Society and hosting meetings,[311] and Mills a vp of the League of Progressive Thought.[312] A week or so later the League report mentioned Knobloch spoke of her recent pilgrimage at the (now mentioned) regular Feasts of the Bahá'í community being held at the Mills home from later January.[313]

In mid-February the League meeting remembered President Lincoln and Mills adding his own comments.[314] A week later Howard and Mrs. MacNutt were mentioned set to come as guests of the Mills and then gave multiple talks including at the Mills home and other receptions in the area.[315] Coverage reached out of the city as well.[316] After the next League meeting,[317] it was announced Mills was to represent the Buffalo Bahá'ís at the national convention.[318] There he appeared in a photograph of delegates of the meeting held March 21, 1909, second row from the front in the center along with Thornton Chase seated two above him to the left.[210]:pp462–3[319] Mills was among those voted for the precursor of the national organization of Bahá'ís in the first Bahá'í national publication that followed.[320] After his return the regular League meeting listing him as a vp,[321] was followed with a remembrance of the 21st Regiment with Mills.[322]

Mills poem "Uplift" was published in a round of newspapers in April-May: another by branch of the Sunshine Society in New Jersey,[323] Detroit,[324] and South Carolina.[325] In mid-May Mills read from the Hidden Words at the memorial for Henry Lee Brent,[326] and then Henrietta hosted a Sunshine Society chapter meeting in their home.[327]

Millsʻ Memorial Day poem “To the devoted departed” was then even more widely published in newspapers: Kansas,[328] Michigan,[329] Wisconsin,[330] Missouri,[331] New Jersey,[332] Montana,[333] Minnesota,[334] Oklahoma,[335] Illinois,[336] Nebraska,[337] Ohio,[338] Colorado,[339] Utah,[340] Pennsylvania,[341] at least. Meanwhile regular Bahá'í meetings were mentioned in the report of the League at the Mills home.[342]

After the regular later June League meeting with Mills listed as vp,[343] and gave a talk at the Hotel Iroquois, then one of the taller buildings of the city, on the Bahá'ís,[344] noted as president of the local Bahá'í community.[345] The talk was published a week later in the regular report of the League as "The Bahai Thought of the Unifications of Religions."[346] He began by reading his "Uplift" poem, outlined the evolution or development of religion and it driving the evolution of humanity - the rise of reason to explain the mysterious and awakening to good and evil "through bitter experiences" which is the connection of the "Law of God and Man" though religion is swept up in passions and "almost become a meaningless clamor" that raises creeds that defenders must refer to theologians and dogmatists. "Of what use, then, is that part of a creed which does not bear on the daily lift of the man and his place and use with men, and if you please, to the good of his soul?" He defined religion as "binding back and restraining of self, that self which is always reaching out for something that the general good, which Divine Law, forbids." From this develops unselfishness and love. He then refers to Bahá'u'lláh, "El Beha", as the "Promised One, Comforter, Spirit of Truth promised by Christ as His own Spiritual return" who teaches "God has developed Himself in the heart of Man from the first and faintest beginnings to the advent, from time to time, in the history of the races of men, of a messenger, arising in the supreme consciousness, of a divine inspiration, as an emanation of and a leader to the Unseen One, the All Pervading." He referred to Moses, Jesus, Muhammad, Krishna, Buddha and Zoroaster and on to Confucius, Socrates and Epictetus all speaking of one God. "… His Manifestation has come in this latter day to tell every soul that the Sea is no more, that continent is joined to continent at last through true brotherhood of man, that the one blood of which He made all the nations of the earth has fused in a new baptism in Christ and all His martyrs - that persecutions and wars shall be no more, and that all barriers between the forms of belief called faiths shall be swept away. This teaching of Beha Ullah(sic) is not an Ism. It has come to do away with the isms by including them all. This is the fire of Love that shall fuse them all in one, the fervent heat that shall melt the earthly elements in man, and cause the heavens of his superstitious imaging to roll up as a scroll and disappear." He then outlines the international presence of the religion in the East and West. "It shines forth from the East even unto the West, not in the twinkling of human eye, not with the sound of a trumpet to the human ear, but in this hour of a Day of a Thousand years: while the green leaf of the bud of humanity is as to the millions of ages since the word went forth, 'let there be light' on a tip of green on the bough of existence to the untold aeons of origin in the soil beneath it.… the dawning of this manifestation, co-incident with the prophetic period of ʻtime, times and a half a timeʻ as reckoned by students of prophecy the world over, as the ʻbeginning of the endʻ and which the Millerites here and abroad prepared for, but a gleam of one moment in the dawn of a latter day."

Henrietta was at the regional Sunshine Society meeting with her listed as one of its directors.[347] There was the regular League meeting early July,[348] followed a week later by the return of Remey coming through giving talks on the religion.[349] After the regular League meeting in early August,[350] Sydney Sprague came and gave a talk on the religion after his return from India introduced by Mills.[351] Then Henrietta hosted a reception and slide show of Adele Gleason who was herself returned from Egypt and the Holy Land and on her way to India.[352] Later in August the Mills hosted a Bahá'í program by Elizabeth Marney Conner,[353] Henrietta had visited the regional summer home for disabled/crippled children,[354] and Mills poem "Uplift" was included in a letter to the editor in Buffalo.[355]

A month later Bahá'í Ahmad Sohrab came to town[356] and gave a talk,[357] which was echoed a month later in a Nebraska newspaper as well.[358] Some two months after hosting Sohrab Henrietta hosted a Sunshine Society event in their home,[359] and an exhibition including some of Mills watercolors followed in mid-December hosted elsewhere[360] while Remey came through again and there was repeated mention of regular Bahá'í meetings at Mills' home.[361] The year closed with the Mills' rented home as part of a property deal.[362]

In January Mills presented a painting of the new commander of the Chapin Post as a part of a GAR reception,[363] Henrietta presented at a meeting of leaders of the Sunshine Society,[364] and in a few days the Mills hosted the Bahá'í meeting with visiting Mary Hanford Ford and her talks,[365] and then Henrietta returned to a Sunshine Society board meeting.[366]

Starting in March Bahá'í meetings at the Mills home was listed in first editions of the Star of the West, the nationally produced Bahá'í magazine.[367] A meeting of the Sunshine Society was held at the Mills home,[368] Henrietta supported a fundraiser of the Colgate University,[369] and approaching the Ridván festival a series of Bahá'ís gave talks at the Mills home: Ella Quant,[370] followed by her and Anna Boylan,[371] and then by Quant and Edward Struven.[372] Mills poem on the early influence on his art, Lars Gustav Sellstedt, a Swedish/Buffalo artist,[373] was published at the end of April.[374] The US Census had the Mills', he registered as a portrait artist, living with two lawyer borders,[375] while daughter Margaret was still a patient at the state hospital,[376] and son Harrison was in Bronx, NY.[377] This was also the year Mills book When Mark Twain lived in Buffalo was published.[378] Extracts of the book began to be published in local papers in mid-April.[379] Mills time working with Samuel Clemens had been mentioned back to 1909,[380] though more after the book was published.[381]

A letter from ʻAbdu'l-Bahá to the Bahá'ís of Buffalo was translated and published in the Star of the West in later June.[382] News there also noted this year Ella Quant was a delegate to the national Bahá'í convention for parts of New York state including Buffalo and that the Buffalo Bahá'í community contributed the Bahá'í Temple Fund in 1909-10.[383] Decades later this became the Baháʼí House of Worship.

Mills' memorial poem was printed late in May,[384] and in June Mill's portrait of the GAR officer was presented to the US Pension Agency and then back to the Buffalo Historical Society.[385] Henrietta went to the state women’s convention of the Federation of Women’s Literary and Educational Organizations of Western New York.[386]

Mills was noted vp for a series of meeting after mid-May for the League through to later July without further word from him.[387] Later in July the Sunshine Society held a luncheon including for Henrietta.[388] Bahá'í meetings advertised in the Star of the West at address of Mills returned in October.[389] Meanwhile Henrietta was amidst Sunshine Society receptions.[390] Across this same period into later November Knobloch returned to give a talk for the League as well as a meeting at the Mills home.[391]

Approaching mid-December the League hosted talks on war and peace by Rev. Leon O. Williams who had been to the 1908 International Peace Congress of London - also addressed by Mills: Mills endorsed William’s talk, tied war to greed, suggested a way to peace with Bahá'ís since “Christ said that he came not to bring peace but a sword. Today by the Bahai revelation mankind has become one race and this is the cycle of co-operation and union of peace and brotherhood.” Another member spoke that peace was impossible until labor and capital and bridged their differences, while another referred to the thought that the Battle of Armageddon was yet to be fought.[392]

Henrietta was listed as the contact for visitors for twice weekly Bahá'í meetings - Thursdays and Sundays[393] and Frank D. Clark of Buffalo contributed books to the Tarbiyat Bahá'í School in Persia through the Persian-American Society across 1910 with the Clarks each sponsoring a separate child at the school as new contributors circa 1911.[394] Mills' poem was published again,[395] and Mrs. E. C. Woodworth had wintered with the Mills leaving mid-February.[396] A March letter of 'Abdu'l-Bahá's responded to a collective letter from a number of New York women including Woodworth,[397] who was also a delegate from Buffalo for the Bahá'í national convention for May 1911 but did not attend; the alternate delegate was another recipient Dr. F. S. Blood.[398] Another recipient of that letter was Dr. W. E. House in Ithaca who had hosted Bahá'í meetings[399] and whose wife Alice was delegate to the national convention from Ithaca in 1920,[400] and was himself a dentist who died February 1921.[401]

The Mills were visited a few days later by a grandson and new bride,[402] and in a couple weeks Henrietta hosted the Sunshine Society.[403]

Mill’s work of the Chronicles of the 21st Regiment began to be noted in remembering 50 years ago for the beginning of the Civil War coverage starting in March 1911 and extending into 1912.[404]

50th anniversary

As 1912 opened the series of articles on the 50th anniversary of the Civil War continued.[405] Son John, who had been born in Colorado, died February 1, 1912, in Toronto.[64][406]

In March Henrietta wrote to the Star of the West Bahá'í magazine saying: "May the beautiful name given by the Blessed Servant of God cause the subscription list to be many times increased and we feel assured that the Star of the West will grow and glow with universal and everlasting light… (sending greetings of the community) hoping one day to 'see Him face to face'",[407] and hosted Sunshine Society meetings at their home in later April.[408] That month Bahá'í Grace Robarts was a guest of the Mills and gave readings at the Hotel Iroquois;[409] she had been the secretary of the Boston Bahá'í community 1910-11.[410] Then Bahá'í Elizabeth Stewart then stayed with the Mills in early May returning from the national Bahá'í convention;[411] she had talked about her trip to Persia at the Mills home.[412]

Bahá'í meetings at the address of the Mills returned noted in the Bahá'í magazine,[413] amidst which Mills contributed a poem to the First Universal Races Congress, (though none of the contributed poems were printed in the proceedings.)[414] That summer Mills visible at community activities in Buffalo and Rochester.[415] There was a break in coverage of events until October when the Mills hosted a meeting at their home.[416] In November Mills' art was part of exhibition,[417] and was mentioned as a GAR officer;[418] Mills spent some time visiting Bull Run and begun doing art based on his review as well as doing a portrait.[419]

As 1912 opened Sunshine meetings were held at the Mills[420] and Knobloch returned to give a talk on the Baha’i Faith at the Mills home in mid-to-late-February.[421] In March the Mills hosting of meetings at their home was noted in Star of the West,[422] and then hosting another Civil War veteran,[423] before GAR meetings[424] amidst which he also attended the funeral of his original 1st Lieutenant of company D.[425] April was also the beginning of coverage of 'Abdu’l-Bahá in America echoed in Buffalo.[426] Mills then wrote a correction to some inquiry made of the Buffalo Evening News that there had in fact been Bahá'í meetings at their home for 6 years in a letter to the editor,[202] and then observed the Feast of Ridvan at their home,[427] during which it was announced 'Abdu’l-Bahá might come to Buffalo soon.[428] Grace Robarts had been the alternate delegate from Buffalo to the national convention for late April 1912,[429] and Buffalo was among communities sending contributions between 1911 and 1912 for the Bahá'í Temple.[430] The visit was delayed however though Mills took the opportunity to speak of the religion again,[431] while 'Abdu'l-Bahá went on to the Mohonk peace conference of 1912.[432]

'Abdu'l-Bahá had given a speech earlier at Howard University about the Civil War and Civil War solder as an impetus of advancing race relations.[433] In later May Mills authored an article for the Buffalo Sunday Morning News reviewing the encampment anniversary of the Buffalo Regiment to near Fairfax and Alexandria roads. The drudgery of living in the encampment after the excitement of anticipating war and some mutual “taking it out” happened. Mills tells the story of a doctor looking for signs of illness and sanitary problems had an unsatisfactory interaction with a soldier whom he then punished but then encouraged often through the fall of 1862 - this may be autobiographical.

Why do I thus go into the intimate detail of matters that can no longer be grievances, when death has long ago paid all scores or the interval of comradeship without regard to former rank softened all bitterness and healed perhaps even self-reproach? Why not forget? Simply because the rising generation looks to us for precept and the value of experience, and the future citizen soldier has the right to know the exact conditions under which he is give away his own person for a season, for the general good and to be admonished of what is due the human feelings that may be subjected to his own authority, and how to bear himself under the control and discipline of others in positions of command. I do not defend the resentment of the boy, he should have saluted and respectfully answered the surgeon in this instance, and waited for dismissal, with the imperturbable front of a man conscious of cleanliness and dignity inviolable. Then he wouldn’t have been tied up and the hectoring would have failed to produce amusement and there would have been less of the aftermath of aggravation.… (describing various kinds and degrees of such punishments in the military then) … I saw these things done, every one of them. I do not believe such things can occur again and do no remember to have ever heard of the like in our service since.[434]

Then he reviews the first Battle of Bull Run, or “Manassas” as it is to the South. He remembers a soldier who lost an arm at the elbow tourniqueted with his own shirt and carrying his musket balanced on this shoulder with great care and moving methodically but unresponsive to questions. Mills wondered if the man was still alive, crawling out after his ambulance transport had broken down to continue some 2 miles back to camp and hospital. “That told of an endurance and faithfulness unconquerable. Think of it. With his musket still on his shoulder. Think of it, Boy Scouts.” Defenses of Washington DC were extended and when his unit advanced again he saw “…abandoned graves in groups of hundreds”. Mills memorial poem for Gettysburg was reprinted in Kansas.[435]

The June 29 meeting of Bahá'ís in West Englewood, New Jersey, included unnamed guests from Buffalo,[436] but later Mills reported that he was himself away to a GAR state convention and then going to see 'Abdu’l-Bahá,[437] was not at a Buffalo march of veterans,[438] and when he returned he gave a review of the religion as well as confirmation 'Abdu’l-Bahá will come, mentions being at the Englewood meeting, and recalls 'Abdu'l-Bahá's Bowery mission visit.[439] “Abdul Baha has won many followers in his going about in spreading the Gospel of religious unity. This is not a new cult. It dates back to 1844. There are assemblies of this cult all over the earth. In Buffalo there has been one for the last seven years. It meets at my home every Sunday and Thursday nights. Its membership is uncertain as we do not believe in putting a tag on the members of various sects who attend, but the meetings usually are attended by fifteen or twenty; sometimes we have had meetings of 100 or more.”

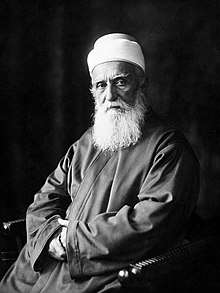

Mills was in the 50th anniversary of recovering from his wounding at Bull Run. 'Abdu’l-Bahá arrived in the evening of September 9.[440] One article said: “Some folks have the impression that Abdul Baha forecasts the end of the world. He said he doesn’t. Asked directly if he predicted the end of the world he smiled in dissent and through his interpreter answered: ʻI know the world has no end. It always will continue as God has created it. If anything is to end, as prophecy relates, it refers to present conditions.ʻ Certainly a meeting is set in the Hotel Iroquois the evening of the 10th.[441]

'Abdu’l-Bahá was escorted by Mills to the Hotel Iroquois that night. His talk is published as follows:

The very cause of life is due to the Supreme One’s love, for by His grace we move, we see, we hear, we feel, and all phenomena is based on His love. The prophets are sent to bear a message of holy love and the philosophers and all the wise men of by-gone ages have sung with sweet melody the theme of love. But alas, the shadow obscuring the sub of affection. Alas, that on earth should breed a contrary spirit in the hearts of men. Alas, that hatred and enmity should spring forth to make a hell of war and bloodshed. Even now in the orient are widows weeping, children lamenting and fathers bereaved for the bloodshed of their dear ones. The continent of Europe is one vast arsenal, which only requires one spark at its foundations and the whole of Europe will become a wasted wilderness. And what flimsy, what impudent pretexts they use: Patriotism, say they, glory, say they; uplifting of the continent, say they. What a travesty on God’s truth.[442]

The next day 'Abdu'l-Bahá spoke at the Church of the Messiah,[443] about 5 blocks from the Mills home, that had been built on land donated by the Albrights that had also founded the Albright Gallery - much later this church merged to become the Unitarian Universalist Church of Buffalo.[444] The minister introduced him saying: "It is my great honor to present to you the prophet of peace, the leader of the Bahá’í Cause. A short history and teachings of this Cause was published in today’s issue of the church newsletter and distributed this evening. I need not therefore dwell on these subjects. I propose to give as much time as possible to this eminent speaker. This great personage has traveled to many parts of the world and has delivered innumerable talks on the question of international peace. In Washington He gave a unique address in a church of our creed. The essential principles of this religion are the same as ours. I feel it an honor that I have been given the privilege of introducing to you the prophet of peace, His Holiness ‘Abdu’l-Bahá."[445] After his talk when it was time to leave the church people came one after the other to meet and the minister encouraged the congregation to go to the Bahá’í meetings. Newspaper coverage mentioned he was heading to Chicago for dedication of the “permanent religious, educational, and charitable center”, currently the Bahá'í House of Worship in Wilmette, and it was said that organized as "Assemblies of consultation” had existed in Buffalo seven years and regularly met at the Mills home, and the community was expecting a “universal house of justice”, an early use of the term now an institution, some day.[201] Buffalo was the only place outside of New York city in the state that 'Abdu’l-Bahá stopped in.[446] A Bahá'í meeting was scheduled a week later,[447] but it was rain delayed,[448] and rescheduled to be at the home of the Mills the next week.[449]

The local news reminded readers of the anniversary of the Second Battle of Bull Run and the wounding of Mills.[450] A month later a suit was settled over a Mills portrait that the former mayor's brother declined won by C. Adell Kayner.[451] In mid-November Mills was officer in Chapin Post of the GAR.[452]

Charles Sprague, Mills' daughter husband, died November, 1912, after months of strokes and was buried in Sandy Creek, New York. He produced an early book of Bahá'í prayers and was a traveling salesman.[453][454][455] In early December Mills presented a painting to the Buffalo Historical Society collection.[456] In early January 1913 Bahá'ís Howard and Mrs. MacNutt stayed at Mills home and gave a series of talks.[457] Mid-January Mills was installed in his office for the GAR,[458] and the Mills hosted the Sunshine Society in their home.[459]

In April the Buffalo Society of Artists held a “faker" adaptation of its artworks in an exhibition including one of Millsʻ[460] followed by a GAR gathering for Gettysburg including Mills.[461] Henrietta, or both Mills, then spent a month in Canada,[462] and Mills was remembered for his Chronicles, art and pen with Mark Twain.[463]

Mills' daughter in law (wife of their first son,) and grandson visited with them in September,[464] followed about 2 weeks later by former Reverend Howard Colby Ives who's talk on the Bahá'í Faith given at Mills home was reviewed in the newspapers.[465]

In late November the veterans of the 21st Regiment met including Mills[466] followed in a few months at the beginning of 1914 with mention Henrietta was at a suffragist meeting,[467] and in February Mills had seven paintings in an exhibition at the Albright Gallery - one owned was a portrait of Charles Walter Couldock[468] done in 1888 and acquired by Buffalo Fine Arts Academy 1905.[469] He also exhibited a "Head" sculpture.[470] Visible activity was much reduced in 1914. Mills presented a plaque for the Buffalo Central High School,[471] the Sunshine club met at the Mills home many times into June.[472] and twenty seven of the last of 21st Regiment came out for event - including Mills - by mid-July.[473] Henrietta hosted guests at their home,[474] and herself attended a Women's Relief Corps meeting at the end of September.[475] A month later Mills attended another funeral of a Civil War veteran.[476] The late December talk of Bahá'ís Remey and Latimer that had been set was rescheduled and announced by Mills.[477]

Last years

January 1915 opened with a Bahá'í meeting with Mills as chair at the Markeen Hotel,[478] and news of a new bronze plaque for the Hutchinson Central High School,[479][480] later the Hutchinson Central Technical High School. The next Bahá'í meetings were also at Markeen, with Mills presiding,[481] and some of his remarks were mentioned in the newspaper coverage - of the religion being a method of unity and peace.[482] before moving the meetings from late February to Mondays at the Mills home.[483] In March the Sunshine Society election noted Mills' poem motto for the group, that it had been organized in 1906,[484] and in April Herietta attended the Woman's Relief Corps meeting.[485] News also came of a Mills painting going to the Panama-Pacific Exposition,[486] as well as the 50th anniversary of President Lincoln laying in state in Buffalo with Mills' service honor guard remembered.[487] In May Mills wrote a letter to the editor he was looking for the missing Lincoln bust and that he had last seen it in 1872 in the gallery of the Buffalo Academy of Fine Arts.[18] A May marriage of their granddaughter brought Henrietta out.[488]

The Mills were noted on the 1915 New York state census.[489] Daughter Margaret was still a patient of the state hospital.[490]

The plaque for the Hutchinson High School was official unveiled in June.[491] Mills was then also photographed in uniform by Spencer Kellogg Jr. for an amateur contest,[492][10] and the 21st Regiment went on its annual outing with Mills along in July.[493] A magazine, The Lake Erie Zephyr, mentioned both Mills poem and Remey's work,[494] and in August the Mills held their 50th wedding anniversary and receptions,[495] at home of Mr. and Mrs. Spencer Kellogg on Lake Erie at Derby.[30] Henrietta was a guest herself.[496] In mid-October Bahá'í Isabella Brittingham, much earlier herself mentioned by daughter Margert, gave a talk at the Mills home,[497] and a few days later Henrietta was at a Woman's Relief Corps meeting.[498] In November Mills contributed to an exhibition by the Buffalo Artists Society.[499]

In January 1916 was a period of some news. Mills joined the Guild of Allied Arts[500] while Henrietta was called a founder of the Woman’s Relief Corps and spoke briefly at a meeting of theirs.[501] In March Mills composed a letter/booklet on the early art of Colorado; [502] and aside from his views on artists and some biographical details it included the advice “Make your calamities serve you.”[6]:pp76,86