John Basset (1518–1541)

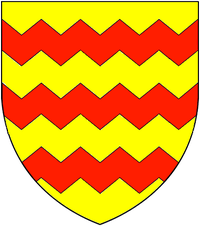

John Basset (1518–1541) was a young English gentleman from Devon, a member of the old Basset family, and heir to a substantial inheritance. His short life is well documented in the Lisle Papers. He studied law at Lincolns Inn and at the age of 20, at the start of a promising career, entered the household of Thomas Cromwell, Lord Privy Seal, but died suddenly aged only 23, albeit having married and produced a son and heir, born posthumously. His stepfather and father-in-law was Arthur Plantagenet, 1st Viscount Lisle (d.1542), Lord Deputy of Calais 1533–1540, a bastard son of King Edward IV and thus uncle of King Henry VIII, whose arrest with that of his mother in 1540 at Calais for heresy and treason, was a major, potentially catastrophic, event in his life. He died a year after the arrests, from an unknown illness, but his siblings all went on to have successful careers, especially his younger brother James, mostly as royal courtiers, apparently unaffected by the crisis.

Origins

John Basset was born 26 October 1518,[1] the eldest son and heir of Sir John Basset (1462–1528), KB, of Tehidy in Cornwall and Umberleigh in Devon (Sheriff of Cornwall in 1497, 1517 and 1522 and Sheriff of Devon in 1524) by his second wife Honor Grenville (died 1566), a daughter of Sir Thomas Grenville (died 1513) of Stowe in the parish of Kilkhampton, Cornwall, and lord of the manor of Bideford in North Devon, Sheriff of Cornwall in 1481 and in 1486.[2]

His siblings included:[3]

- George Basset (b.circa 1522–5), second son, MP.

- James Basset, MP, third son and youngest child, a courtier first to Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester and Lord Chancellor, later as a courtier to Queen Mary I.

- Philippa Basset (b.1516), eldest daughter;

- Katharine Basset, a servant to Queen Anne of Cleves.

- Anne Basset (b.1521), third daughter, a courtier, maid of honour successively to Queens Jane Seymour, Anne of Cleves, Catherine Howard and Katharine Parr,[4] allegedly considered as a wife of King Henry VIII and may have been one of the Mistresses of Henry VIII.[5]

Youth

John's first ten years of childhood were probably spent at his father's principal seats of Umberleigh in Devon and Tehidy in Cornwall. After his father's death in 1528 John was brought up by his mother Honor Grenville and stepfather, Arthur Plantagenet, 1st Viscount Lisle (d.1542), Lord Deputy of Calais, uncle of King Henry VIII. His mother's second marriage elevated the family from prominent West Country gentry into the highest circle of Tudor society, and also (by John's marriage to his step-sister) infused into them the royal blood of the last of the House of Plantagenet.[6]

Wardship

To John Worth and his mother

His father died in 1528 when John was still a minor aged 10 and on 29 May 1528 his wardship and marriage was purchased for 200 marks by John Worth of Compton Pole, Devon, Sewer to the Chamber of King Henry VIII, in partnership with his mother, still then Lady Basset.[7] John Worth was a distant cousin of his ward, being 8th in descent from John Worth (alias Wrothe) of Worth in the parish of Washfield near Tiverton in Devon, who married Margaret Willington, the second daughter and co-heiress of Sir John Willington of Umberleigh.[8] Yet Umberleigh did not descend in the male line of the Worth family as Margaret Willington bequeathed Umberleigh to her daughter Elizabeth Worth who married Sir William Palton, thus Umberleigh stayed in the Palton family for three generations until the family died out in the male line and Umberleigh reverted to the Beaumonts of Shirwell, surviving heirs of the Willingtons.[9] Isabel Willington, the eldest sister of Margaret Willington and her co-heiress, had married William Beaumont (1376–1408) of Shirwell, whose eventual heir to Shirwell and to Umberleigh was the Basset family.[10]

To Lord Lisle

Before 1532 however John Basset's wardship and marriage had been purchased by his step-father Lord Lisle[11] who wishing to provide her a wealthy husband, married him off to his daughter, thus Basset's step-sister, Frances Plantagenet. In 1533 Lord Lisle was appointed Lord Deputy of Calais and moved there with Lady Lisle, John's mother, leaving John at Lord Lisle's manor of Soberton in Hampshire from 1533 to 1535.[12]

Education

John's education is well recorded in the Lisle Papers, covering the period 1533 to 1540, held at the UK National Archives. Three of his letters to his mother survive in this collection,[13] but most of the references to him are contained in letters written to his mother and step-father in Calais by their London business agent John Husee, who advised them and made practical arrangements and who knew his way amongst court and legal circles. He studied Latin for 14 months under the parson of Colmer.[14] In 1534 aged 16 he entered Lincolns Inn to train in the law, where he remained until 1536.[12] Much detail of his life as a trainee lawyer are preserved in the Lisle Papers, mainly in the letters from John Husee to Lord and Lady Lisle, concerning domestic matters such as the clothing he required, rent of his chambers, financial allowance, his recreations, etc. It was Husee who arranged for John's admittance to Lincolns Inn and who found him a law tutor and chambers, and who advised John on his clothing requirements and how to decorate his chambers.[15] John had his own servant who lived with him named "Bremelcum". Husee wrote the following letter to Lady Lisle on 27 January 1535:[16]

"My humble duty premised unto your good ladyship...Mr Basset is all out of apparel. He hath never a good gown but one of chamlet the which was very ill-fashioned but it is now a'mending. His damask gown is nothing worth, but if it be possible it shall make him a jacket, for his coat of velvet was broken to guard his camlet gown. His satin jacket is meetly good and the other two nothing worth. His two doublets will serve, the third is but easy. He hath but one pair of white hosen and the kersey is not for him, therefore I have sent it by Edward Russell. More, he hath brought with him a feather bed, bolster, blankets, counterpoint and two pair of sheets. He must have another bed furnished with a pillow, tester, saye or other, with curtains. Madame, I intend to make him two pair of black hosen, a new gown of damask faced with foynes or genettes, and a study gown faced with fox pelts of cloth of five shillings the yard. His damask gown shall be guarded with velvet. And if I can compass it he shall have a gown of fine cloth furred with bogy, with a small guard of velvet; and his old damask gown shall make him a jacket. And this done he shall be well apparelled for this two years. He must have wood and coal in his chamber. And less than here written he cannot have to be anything likely apparelled as appertaineth to his birth...Bremelcum would have a new coat, for he hath but one..."

Career

By 12 October 1538 the 20-year-old John had been placed in the household of Thomas Cromwell, Lord Privy Seal, chief minister to King Henry VIII. Lady Lisle was at this time petitioning Cromwell over the complex legal issues which were separating her son John from his Beaumont inheritance. At first John served as a waiter, which involved him being admitted every day to Cromwell's audience chamber when suitors presented their suits to the Lord Privy Seal.[17] Such a career move had earlier been suggested by George Rolle, who believed that from serving Cromwell, John Basset might more easily progress to serving the king himself.[18] His career was cut short by his early death in 1541 at the age of 23.

Beaumont inheritance

John Basset as well as being heir to his extensive paternal lands was also heir to his maternal great-grandmother Joan (or Johanna) Beaumont[19] (wife of John Basset (1374–1463)), the eldest daughter of Sir Thomas Beaumont (1401–1450) of Shirwell by his wife Philippa Dinham, daughter of Sir John Dinham (1406–1458)[20] of Nutwell, Kingskerswell and Hartland. Joan Beaumont was heiress to her brother Sir Philip Beaumont (1432–1473), MP in 1467 and Sheriff of Devon in 1469, and also to her mother Phillipa Dinham.[20]

These former Beaumont lands included the manors of Umberleigh and Heanton Punchardon in North Devon. However, as deduced by Byrne (1981), Basset's father (Sir John Basset (1462–1528)) lacked the financial resources to recover his inheritance,[21] which involved paying fines and recoveries to the King. At the time he had been married for 30 years[21] to his first wife Elizabeth Denys and had given up any hope of producing a surviving son and heir. To make the best of his situation, he obtained financing for the recoveries from Giles Daubeney, 1st Baron Daubeney (1451–1508), KG, under a special agreement entered into in 1504, referred to by the family as the "Great Indenture".[22] This specified that Daubeney would pay about £2,000 for the recoveries on condition that one of the Basset daughters and co-heiresses would marry Daubeney's son Henry Daubeney (1493–1548) (later created Earl of Bridgewater), then aged 10, before his 16th birthday. The purpose was to entail the Beaumont lands upon the male issue of a Daubeney-Basset marriage, thus increasing the future wealth of the Daubeney family. However the indenture allowed for Sir John Basset and any future wives of his to retain possession of Umberleigh and lands in Bickington during their lives. If the scheme should fail due to the marriage not taking place and in default of other provisions, the lands would revert to the right heirs of Basset. To this effect Basset sent two of his four daughters by his first wife Elizabeth Denys, namely Anne and Thomasine, to live in the Daubeney household.

The marriage never did take place and Lord Daubeny died four years later in 1508. Whether for those reasons or another the gamble paid off for John Basset (1462–1528) as his second wife Honor Grenville produced for him a son and heir in 1518 and the Beaumont lands eventually came back to the Basset family, not without great struggles.

During the time when the agreement was operative the deeds to the properties concerned were kept in safe custody by Richard Coffin (1456–1523)[23] of Portledge, Sheriff of Devon in 1510,[24] the Beaumont's tenant at Heanton Punchardon and at East Hagginton[25] (in the parish of Berrynarbor), who was clearly trusted by both parties,[26] and whose Easter Sepulchre tomb survives in the chancel of Heanton Punchardon church.[27] Basset's son George later married Richard Coffin's great-granddaughter Jacquet Coffin.[28] The custody of these deeds forms an important topic in the Lisle Letters.[29] The matter of John Basset's inheritance had not been resolved at the time of his death in 1541, despite intervention at the highest level from his master Thomas Cromwell.[17]

Marriage and children

In 1538[30] he married Frances Plantagenet, the daughter and co-heiress of his warder and step-father Arthur Plantagenet, 1st Viscount Lisle, bastard son of King Edward IV . She survived him and married secondly Thomas Monke (died 1583), of Potheridge in Merton, Devon (as his first wife), with whom she had three sons and three daughters. By her eldest son from this second marriage she was great-grandmother of George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle (1608–1670), KG.[31] By Frances Plantagenet John Basset had the following children:

- Honor Basset, born at Calais in May 1539.[32] Shortly after her birth in 1540 disaster fell on the family with the arrest of Lord and Lady Lisle on suspicion of heresy and treason. Lord Lisle was sent to the Tower of London where he died in 1542, while Lady Lisle was kept under house arrest in Calais until after her husband's death. It appears that before June 1540 John went swiftly to Calais after hearing the news and brought back his wife and daughter to England.[32]

- Sir Arthur Basset (1541–1586), born posthumously on 4 October 1541,[32] eldest son and heir, MP, of Umberleigh.[33] Due to his Plantagenet ancestry, Arthur's son Sir Robert Basset (1573–1641) made what turned out to be a foolish and costly decision to offer himself as one of the many claimants to the throne of England after the death of Queen Elizabeth, perhaps encouraged by his father-in-law Sir William Peryam, Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer.[34] He suffered a heavy fine for his action which according to the biographer John Prince (died 1723), involved the sale of thirty of the family's manors.[35]

- Eleanor Basset, married to William Whiddon.[36]

Death and succession

John Basset died on 20 April 1541,[37] having made his will on 17 April 1541, "whole and perfect of mind and memory and sick of my body", and was succeeded by his son Sir Arthur Basset (1541–1586). He was buried in unknown location ""whereas it shall please my friends". One of the witnesses to his will was his fellow North Devonian, the lawyer George Rolle (d.1552),[38] who had done much to assist his mother and step-father in attempting to recover his Beaumont inheritance.[39] He bequeathed all his estates in Devon, Cornwall and Wiltshire to his wife Frances for her life, "towards her living and advancement", whom he appointed his sole executrix and to whom he left all his goods and chattels. He listed his manors of Trevalga and Femarshall in Cornwall; Whitechapel, Holcombe, Upper Snellard, and lands in the parish of Chudleigh in Devon; and Calston in Wiltshire.[38] These manors and the principal seats of Tehidy, Umberleigh and Heanton Punchardon eventually descended to his male heirs.

References

- Per Inq p.m. of his father, per Byrne, vol 1, p. 313

- Richard Polwhele, The Civil and Military History of Cornwall, volume 1, London, 1806, pp 106–9; Byrne, vol.1, p. 302 states "1485", quoting Public Record Office, Lists & Indexes, vol.IX, List of Sheriffs

- Byrne, vol.6, pp. 276–7

- Byrne, vol.6, p. 277

- Hart, Kelly (1 June 2009). The Mistresses of Henry VIII (First ed.). The History Press. p. 197. ISBN 0-7524-4835-8.

- Lord Lisle was the last, albeit illegitimate, in the direct male line of the Plantagenets, descendants of King Edward III

- Byrne, vol.1, p. 315

- Vivian, pp. 805–8, pedigree of Worth of Worth

- Pole, pp .422–3, descent of manor of Atherington

- Vivian, p. 46, pedigree of Basset

- Byrne, vol.1, p. 316

- Byrne, vol.6, index, p. 321

- Byrne, vol.1, p. 87

- Byrne, vol.4, p. 1

- Byrne, vol.4, p. 13

- Byrne, vol.4, letter 826, pp. 17–18

- Byrne, vol.4, p. 88

- Byrne, vol.4, p. 87

- Byrne, vol.1, p. 312

- Vivian, p. 46

- Byrne, p. 313

- Transcribed in Byrne, vol.4, chapter 7, appendix 2

- Byrne, vol.1, p. 605; Vivian, p. 208, pedigree of Coffin; Byrne, vol.1, p. 606: "died in Dec 1523 at age of 77"

- Risdon, Tristram (d. 1640), Survey of Devon, 1811 edition, London, 1811, with 1810 Additions; Pevsner, p. 477

- Byrne, vol.1, p. 605; East Hagginton had descended to the Beaumonts from the Punchardon ("Pont de Chardin") family of Heanton and in Risdon's time (d.1640) was still held by the Coffin family. In 1810 it had reverted to the Bassets (Risdon, pp.347,431)

- Byrne, vol.1, pp. 605–6

- Pevsner, Nikolaus & Cherry, Bridget, The Buildings of England: Devon, London, 2004, p. 477

- Byrne, vol.1, p. 605; Vivian, pp. 47, 209

- Byrne, vol.1, p. 605

- Byrne, vol.6, index, p. 322

- Somersetshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Proceedings, Volume 44, p. 12

- Byrne, vol.4, p. 89

- Somersetshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Proceedings, Volume 44, p. 12

- Biography of Sir Robert Basset in History of Parliament

- Prince's "Worthies of Devon", biography of Col. Arthur Basset (1597–1672)

- Vivian, p. 47

- Year of death per History of Parliament biog. of his son Sir Arthur Basset who "succeeded father 1541"; day & month from Somersetshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Proceedings, Volume 44, p. 12

- Byrne, vol.6, p. 260

- Byrne, several refs

Sources

- Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitations of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620, Exeter, 1895.

- Byrne, Muriel St. Clare, (ed.) The Lisle Letters, 6 vols, University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London, 1981, vol.1

- Pole, Sir William (d.1635), Collections Towards a Description of the County of Devon, Sir John-William de la Pole (ed.), London, 1791