Joe Magarac

Joe Magarac is a pseudo-legendary American folk hero. He is presented to readers as having been the protagonist of tales of oral folklore told by steelworkers in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, which later spread throughout the industrial areas of the Midwestern United States.

Origin

Magarac first appeared in print in a 1931 Scribner's magazine article by Owen Francis, who said he heard the story from Croatian immigrant steelworkers in Pittsburgh area steel mills.

However, field research in the early 1950s failed to uncover any traces of an oral tradition about the character, meaning that Joe Magarac, like Big Steve and Febold Feboldson, probably belongs in the category of "fakelore," or stories told folk-tale style that did not actually spring from authentic folklore.[1][2]

Legend

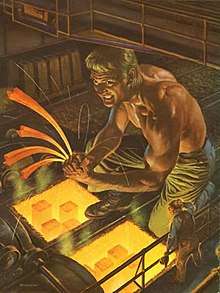

Joe Magarac ['magarats] whose name means "donkey" in Croatian[3], is variously described as Hungarian, Serbian, Croatian, or Bohemian.[4] Joe Magarac stories were told in many industrial cities of the Midwest, though his home was always Pittsburgh. Magarac has been depicted as a patron saint for steelworkers. He was reputed to be able to do the work of 29 men, because he worked 24 hours per day, 365 days per year.[5]

He lived at Mrs. Horkey's boarding house and was physically made of steel. He was allegedly born inside—or on the outside of—an ore mountain and rose out of an ore mine to help steelworkers. He would appear at critical moments to protect steelworkers, for example to stop the falling of a 50-ton crucible on a group of steelworkers.[6]

Marriage

Magarac won the beautiful Mary Mestrovich's hand in marriage in a weight-lifting contest, but he allowed her to marry her true love Pete Pussick.[7]

Magarac's fate

His fate is debated as well. While one version of the tale states that he melted himself down in a Bessemer furnace for material to build a new mill, another states that he is still alive. The second version suggests that he is waiting at an abandoned mill, waiting for the day that the furnace burns again.[8]

Whether Magarac is still living often rests on his ability to change from steel into human form. In the comic "Joe Magarac and His U.S.A. Citizen Papers" written by Irwin Shapiro and illustrated by James Daugherty, in which Magarac is a superhuman immigrant made of steel. He is melted down into steel and becomes part of the US Capitol Building; after hearing two bigoted politicians discussing immigration, Magarac returns to human form and goes to war against Washington, D.C.[9][10]

Legacy

Pittsburgh's local amusement park, Kennywood, had a depiction of Joe Magarac as a scene for the Olde Kennywood Railroad. During the slow moving, historic and culturally entertaining ride, Joe Magarac was depicted with a red-hot steel beam, bending it into shape for the amusement park's steel coasters. In 2009, the statue was donated to US Steel Corporation and has since been re-erected at the entrance to the company's Edgar Thomson Works.[11]

In downtown Pittsburgh, the 300 Sixth Avenue Building displays a polychrome frieze of Magarac. The garden adjacent to the Children's Museum of Pittsburgh hosts sculptures of Magarac and other figures, designed by sculptor Charles Keck and rescued from the Manchester Bridge when it was razed in 1970.

One version of the Magarac story was recorded in song by The New Christy Minstrels on their 1964 Columbia Records release Land of Giants: "We're gonna build a railroad down to Frisco and back, and way down to Mexico. Who's gonna make the steel for that track? It's Joe... Magarac."[12][13]

A large statue of Joe Magarac pouring molten steel is a prominent landmark in the city of Steelport in Saints Row: The Third. The statue is also highlighted in Saints Row IV as a weapon which the player uses to fight a giant energy drink mascot.

See also

References

- "Pennsylvania Folklore, or is it Fakelore?". Archived from the original on 2013-05-16. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- Gilley, Jennifer; Stephen Burnett (November 1998). "Deconstructing and Reconstructing Pittsburgh's Man of Steel: Reading Joe Magarac against the Context of the 20th-Century Steel Industry". The Journal of American Folklore. 111 (442): 392–408. doi:10.2307/541047. JSTOR 541047.

- "Joe Magarac, a legendary Croatian steel worker in the USA". www.croatia.org. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2011). "Labor Songs". The Civil War era and Reconstruction : an encyclopedia of social, political, cultural, and economic history. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 9780765682574. OCLC 690904693.

- "Larger than Life Folk Heroes- Making a Living - Johnstown Heritage Discovery Center". www.jaha.org. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- "Larger than Life Folk Heroes- Making a Living - Johnstown Heritage Discovery Center". www.jaha.org. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- "Larger than Life Folk Heroes- Making a Living - Johnstown Heritage Discovery Center". www.jaha.org. Retrieved 2017-12-05.

- Wills, Rick (March 13, 2008). "Visitor brings steel man tall tale to life for Pine students". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- "The Steel Man Reaches Out Across Time | www.constellations.pitt.edu". constellations.pitt.edu. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- Shapiro, Irwin; Daugherty, James Henry (1948). Joe Magarac and His U.S.A. Citizen Papers. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 9780822953050.

- Pennsylvania Giants, accessed 10/27/12

- "Joe Magarac - The New Christy Minstrels | Song Info | AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- Tell Tall Tales! Legends and Nonsense / Land of Giants, Collector's Choice, 2003-07-08, retrieved 2017-10-06