Joe Acanfora

Joe Acanfora (born July 6, 1950 in Jersey City, New Jersey) is an American educator and activist. Acanfora, who is openly gay, fought to become an earth science teacher in the public schools in Pennsylvania and Maryland in the early 1970s. His fight between 1971 and 1974 over a series of transfers and dismissals by authorities from his public school teaching assignments based upon his acknowledged homosexuality involved litigation through the federal court system; expert witness court testimony on the effect of an openly gay teacher on his students; extensive media coverage, including an "episode appearance" on CBS 60 Minutes; a "morality investigation" by the Penn State University Teacher Certification Council; and active participation of his parents in the public debate.[1]

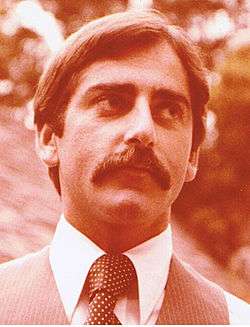

Joe Acanfora | |

|---|---|

self portrait | |

| Born | July 6, 1950 Jersey City, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Education | B.S. 1972, Penn State University |

| Occupation | educator; university administrator |

Childhood

Joseph Acanfora, III was born in 1950 to Leonore and Joseph Acanfora, II. At the age of five, Acanfora and his family moved from Jersey City to Brick Town, New Jersey.[2] Acanfora is the oldest of three children, with a sister being born in 1961 and another sister born 1964.[3] As a young child, Acanfora was interested in the weather, and this interest turned into a passion for meteorology. His mother said that Acanfora "...once tried to eat chicken wings so he could fly up to the clouds and look at them close up."[2] This passion was also spurred by Acanfora's seventh grade science class teacher, who was a former Navy meteorologist.[2] Acanfora graduated as valedictorian of his class from Brick Township High School, in Brick Township, New Jersey in 1968.

Penn State college days

Acanfora entered Pennsylvania State University in fall 1968, with the intent to major in meteorology and participate in the Navel Reserve Officers Training Corps.[2] At the end of his sophomore year, Acanfora realized he wanted to teach and decided to major in secondary education.[2] In his junior year, he joined, and soon thereafter became Treasurer of the Homophiles of Penn State (HOPS), a newly formed campus organization dedicated to protecting the civil and constitutional rights of homosexuals and increasing public understanding of homosexuality. When the University refused to grant official recognition to the organization, four of its members, including Acanfora, instituted legal action to compel such recognition. That action, which ultimately was successful, received considerable local publicity, in the course of which Acanfora acknowledged that he was a homosexual.

At the time that his acknowledgment became public, Acanfora was fulfilling the student teaching assignment that was necessary to obtain his teaching degree from Penn State at Park Forest Junior High School located in State College, Pennsylvania. That school system and Penn State immediately suspended his student teaching status upon learning of his homosexuality and membership in HOPS. Acanfora thereupon instituted legal action seeking reinstatement as a student teacher, and obtained an immediate court injunction granting such reinstatement. He successfully completed the student teaching assignment with a grade of "B" and graduated from Penn State in June 1972.[4]

As his senior year was coming to a close Acanfora applied for certification to teach in Pennsylvania. The question was raised by the Penn State dean of the College of Education, Dean Abram VanderMeer, as to whether a homosexual could have the requisite "good moral character" necessary for certification.[5] This issue became a subject of great campus, county, and statewide controversy, including an interrogation of Acanfora by six Penn State deans who made up the University Teacher Certification Council. When the Council deadlocked 3–3 on whether or not Acanfora possessed a "good moral character", the matter was referred to the then Pennsylvania Secretary of Education, John C. Pittenger, for decision.[6] With his Pennsylvania status in this undecided posture, Acanfora sought and found employment as a teacher with the Montgomery County Public Schools in Maryland.

Employment in Montgomery County, Parkland Junior High School

Spring & summer 1972

In April 1972, Acanfora applied for employment with the Board of Education of Montgomery County, Maryland. In the application process, he was asked to list his "professional, service and fraternal organizations", and for a list of "extracurricular activities" he had engaged in as a student.[7] He did not list his membership in the Homophiles of Penn State in response to either question. In later court trials, Acanfora would admit that "...he realized that this information would be significant, but he believed disclosure would foreclose his opportunity to be considered for employment on an equal basis with other applicants."[7]

On May 19, 1972, Acanfora was interviewed by a personnel specialist in the Department of Personnel for Montgomery County Public Schools. Following the interview, the personnel specialist filled out an "interview and recruitment form" which is a standard part of each applicant's file. Acanfora was rated above average in each of the seven categories contained on the form (appearance, personality, verbal expression, knowledge of subject area, enthusiasm for teaching, references, and scholarship). In the "comments" section, the interviewer described Acanfora as "an above average earth science applicant." However, the interviewer had acquired a subjective "gut feeling" during the interview that Acanfora might be a homosexual, and so he added the following comment on the form: "Principal must interview before contracting; reservations."

Despite this caution, Acanfora was hired without further interviewing by the Assistant Principal of Parkland Junior High School in Rockville, Maryland, and entered into a one-year teaching contract. He was one of 719 new teachers hired in Montgomery County in 1972, out of 10,000 applicants. Acanfora commenced his duties as an eighth grade earth science teacher on August 29, 1972. His teaching performance was judged entirely satisfactory by his supervisor.[8]

Suspended from teaching

On Friday, September 22, 1972, Pennsylvania Secretary of Education Pittenger called a press conference to announce that he had decided to certify Acanfora. That weekend, a New York Times article from September 24 and a Washington Evening Star-News article from September 23 reported the decision of the Pennsylvania Secretary of Education, and noted that Acanfora was then currently teaching in Montgomery County, Maryland.[9]

On the following workday, Monday, September 25, the principal of Acanfora's school addressed a memo to the Deputy Superintendent of Schools, Donald Miedema, recommending that Acanfora "be considered for removal from his teaching position as soon as possible . . . in anticipation of the disruption which can materialize when this becomes known in the community." Miedema, in turn, addressed a memo to the Board of Education advising that "one of the alternatives which we are exploring is the reassignment of Mr. Acanfora with full salary, to a position that does not require contact with youngsters."

On the following day, Miedema addressed a letter to Acanfora informing him that he had been transferred from his classroom teaching position to "a temporary alternate work assignment"[8] in the headquarters building "while we gather information and assess the circumstances relating to this matter." The letter stated that the transfer was "in no way to be construed as punitive action. You will receive full salary while you are in this temporary work assignment."[6]

Acanfora's "temporary alternate work assignment" was an office job created for him in which his duties largely were "make-work." It was revealed in court testimony that in that position, Acanfora was denied the opportunity to teach and deprived of the opportunity to gain experience and receive evaluations critical to a teacher's ability to secure renewal of teaching employment beyond the first year. Although Acanfora's salary was not reduced, the district court would find later that the transfer breached the "clearly implied promise of continued employment in a classroom teaching capacity for the duration of [his] contract."

At trial in Baltimore Federal District Court, Miedema explained the factors which prompted him to transfer Acanfora. The newspaper stories reporting Acanfora's certification had recounted his suspension from his student teaching position and the controversy which had attended his request for certification, and Miedema wished to investigate the facts underlying the suspension and delay in certification. Additionally, Miedema was "concerned" that Acanfora might be "an activist, advertised homosexual." Finally, Miedema was worried about "community concern and reaction" to the newspaper disclosures that a homosexual was teaching in the school.

Montgomery County School officials took steps to assure that Acanfora would have no contact whatsoever with students. The junior high school needed to have him return to the school to assist in preparing his former students' grades, but he was instructed not to arrive at the school until the students had left for the day. On another occasion, when he requested the opportunity to participate in a teacher workshop, he was told that he could not attend because students would be present.

Although Acanfora performed the office work to which he was transferred, he repeatedly requested that he be reinstated to his classroom position. These requests were denied, Acanfora being advised that the transfer would remain in effect pending investigation, but that the transfer was "in no way to be construed as punitive action."

In fact, as the district court later found, the investigation conducted by respondents was "cursory." Miedema wrote to Penn State University and to the Secretary of Education for the State of Pennsylvania requesting information about Acanfora's suspension from his student teaching position and the controversy concerning his certification. Penn State responded that Acanfora had "successfully completed the student teacher assignment", and that the brief suspension therefrom had been motivated by his joining the lawsuit to obtain accreditation of HOPS, a suspension which all concerned had recognized to be an invasion of Acanfora's constitutional rights and which had been quickly corrected. The Secretary of Education responded that Acanfora's performance as a student and as a student teacher had been satisfactory in all respects, and that he had deemed Acanfora to be of "good moral character" in deciding to certify him. Both responses were received by Miedema in late October.

At no time throughout the "investigation" which was the ostensible reason for the "temporary" transfer, did school authorities make any inquiry concerning Acanfora's conduct as a classroom teacher at Parkland Junior High School, nor was he offered or provided a hearing of any kind.

Although court testimony revealed the "investigation" was completed upon receipt of the letters from Pennsylvania, and although those letters contained nothing but praise for Acanfora, Montgomery County Schools did not reinstate him to the classroom.

The transfer of Acanfora became a subject of great public interest, both locally and nationally. Acanfora accepted invitations to appear on several radio and television programs including CBS's 60 Minutes, which devoted a 20-minute segment to the case, entitled "The Case of Joe Acanfora"."60 Minutes video here" The substance of his remarks in all those appearances was threefold, that:

- employment discrimination against homosexuals was unjust,

- he would never discuss his sexual orientation with students in or out of school, and

- he hoped that greater public understanding of homosexuals would develop.

Acanfora v. Board of Education: Proceedings in the U.S. District Court in Maryland

On November 7, 1972, Acanfora instituted a lawsuit against the Board of Education, the Superintendent (Dr. Elseroad), and the Deputy Superintendent (Dr. Miedema), under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 in the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland. The complaint alleged that:

- Acanfora had been transferred for constitutionally impermissible reasons, and

- he had been denied procedural due process.

An extensive trial ensued in the federal District court in Baltimore, Maryland.

Much of the trial was devoted to eliciting the facts outlined above. Acanfora testified regarding the philosophy that guided him in his professional role as a teacher. He explained in his testimony that in his view it would be wholly inappropriate for a teacher to discuss his sexual orientation with students. He would not, and had not, discussed any aspects of sexuality either with students or fellow faculty members. He would not advocate, and had not advocated, that any other person participate in homosexual activities. Asked how, if he were reinstated, he would respond to students who might inquire about his homosexuality. Acanfora testified that he would tell students that he did not inquire into their personal lives and that he wished them not to inquire into his. Acanfora's supervisor testified that his teaching performance had been wholly satisfactory. Students of Acanfora testified that he was a popular and effective teacher and that they hoped he would be reinstated. Students and faculty alike had sponsored petitions urging Montgomery county Schools to reinstate him. (Both the local Montgomery County Education Association and the National Education Association, the largest teachers' group in the U.S., lent their support.[10]) The record contained no evidence that any students, parents, or faculty members objected to his reinstatement at the time.

In addition to testimony concerning the facts, both sides introduced concerning the possible effects of Acanfora teaching in the classroom. The experts were unanimous that there is generally no danger in homosexuals teaching in the public schools. However, Montgomery County School Board's experts contended that the return of Acanfora to the classroom might conceivably be dangerous because of the conjunction of two additional facts:

- as a result of the publicity, his students would be aware of his homosexuality, and

- he taught at a grade level in which students were entering adolescence.

In their view, if Acanfora was an effective and popular teacher he would constitute a "role model" for his students. The experts feared that a "relatively few" students who enter adolescence with "extreme emotional disturbances" might be so impressed with Acanfora as a teacher that they would seek to emulate him in all respects, and thus decide to become homosexuals. The experts likened their view that Acanfora be excluded from the classroom to an "inoculation program" even though only a "handful of individuals" might be affected, he should be excluded. They acknowledged that their concerns were wholly speculative, that there was no relevant data on the subject, and that there is no known instance of a homosexual teacher, simply because he was known to be a homosexual, having an adverse effect on even a single adolescent.

Acanfora's experts disagreed with this speculation, advancing several reasons why Acanfora's impressiveness as a teacher would not result in students becoming homosexuals to emulate him.

The Superintendent of Schools, Dr. Elseroad, testified that he opposed reinstatement of Acanfora, for three reasons:

- Acanfora had "withheld information on his application" i.e. his membership in the Homophiles of Penn State,

- employment of a known homosexual in the classroom "increases the risk of having a good model available for students in the public schools", and

- because Acanfora's homosexuality "has become widely-known and highly publicized", returning him to the classroom "would involve that school in a swirl of controversy. . ."

On May 1, 1973, after the trial but prior to the district court's decision, Montgomery County Schools notified Acanfora that his employment would not be renewed for the 1973–74 school year. The notification did not state the reasons for non-renewal, but its issuance came only two weeks after Dr. Elseroad's testimony as to the reasons why he did not believe Acanfora should be reinstated to the classroom. The district court reopened the record, at Acanfora's request, to admit the non-renewal notice into evidence.

District Court's opinion

The district court found that it was "quite clear from the evidence that the essential reason for the transfer was that Acanfora is an admitted homosexual", and that "the Board of Education would not knowingly hire a homosexual". "The Board has in no way attacked Acanfora's classroom performance, nor has it charged Acanfora with bringing up the subject of homosexuality in the school environment. The evidence is that he is competent and that he did not discuss his private life while at school".

Declaring that "the time has come today for private, consenting, adult homosexuality to enter the sphere of constitutionally protectible interests", the court ruled that one's right to be a homosexual is protected by the First Amendment's freedom of association and by the right of privacy enunciated by this Court in, inter alia, Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

The court concluded, therefore, that Acanfora could be removed from the classroom, and his protected interests thus transgressed, only if there were an overriding state interest justifying that action. The only evidence which had been proffered by respondents going to that issue was the testimony of their experts, and accordingly the court recounted all of the expert testimony in great detail. The court concluded that respondents had not sustained their burden of proving an overriding state interest. While it would be "premature to state definitively that Acanfora's presence in the classroom would have no deleterious effect", the risk, albeit "not illusory", "does not seem as great or as likely as defendants have assumed". The court concluded that "the 'board of education's policy of not knowingly employing any homosexuals is objectionable"; that "mere knowledge that a teacher is homosexual is not sufficient to justify transfer or dismissal"; that a teacher need not hide his homosexuality in order to retain his teaching position; that the transfer was "arbitrary" and "without legal justification as matters then stood"; and that the transfer was a "transgression" by Montgomery County Public Schools.

The district court also held that Acanfora had been denied procedural due process. Acanfora had a "clearly implied promise of continued employment in a classroom teaching capacity for the duration of [his] contract", and thus a property interest which could not be taken away without procedural due process. Additionally, the precipitous transfer was "an implicit allegation that his homosexuality determines unfitness to teach", and thus interfered with his liberty interests. Since defendants transferred him without any prior investigation or hearing, and thereafter conducted only a "cursory investigation" without even then providing him any hearing, he was denied procedural due process.

Despite these rulings, the district court held that Acanfora was entitled to no relief for any of the constitutional violations committed against him. With respect to the substantive violations, the court held that Acanfora's post-transfer appearances on radio and television programs disqualified him from entitlement to relief. Those appearances "were not reasonably necessary" for "self-defense", and would likely spark unnecessary controversy regarding the subject of "homosexuality and the classroom".

"Accordingly, despite the initial transgression of the defendants, the Court cannot grant plaintiff the relief for which he prays. Plaintiff's public activities as herein described are not 'protectable' and the Court cannot at this time characterize the refusal to reinstate plaintiff or renew his contract as arbitrary or capricious under either the First Amendment or the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment."

With respect to the procedural due process violations, the district court thought them cured by the de nova trial which Acanfora received in his lawsuit: "The parties have shifted their attention to the plenary hearing in this forum".

4th Circuit Court of Appeals' decision

On appeal, the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals issued its decision concluding that Acanfora's post-transfer public appearances were protected by the First Amendment, and that "they do not justify either the action taken by the school system or the dismissal of his suit [by the district court]".

Nevertheless, "without reaching Acanfora's claim that his denial of a teaching position is unconstitutional, we affirm the district court, but on different grounds". In the view of the court below, Acanfora "is not entitled to relief because of material omissions in his application for a teaching position".

The court found controlling a series of decisions in which this Court and other courts of appeals have held that one who is prosecuted or otherwise punished for lying to the Government may not defend by attacking the constitutionality of the question which elicited the lie. Acanfora had argued that these cases were inapposite "because the school officials transferred him on account of his homosexuality, not the omission from his application". The court acknowledged, as the district court had found, that the transfer was not motivated by the omission from the application. Nevertheless, it found the cases controlling for two reasons. First, to limit the cases to prosecution or punishment for lying would constitute "an unduly restrictive application of the principles expressed" in those cases. Second, respondents should not be "prejudiced" by their failure to rely upon the omission as a motivation for transferring Acanfora, for at that time they only suspected that the omission was deliberate and it was not until trial that the suspicion was confirmed. The court noted that at trial the Superintendent had testified that the omission was one of the reasons which made him unwilling to reinstate Acanfora, and concluded that this was sufficient to warrant application of the "lying to the Government" cases.

With respect to the procedural due process issue, the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals merely reiterated the district court's reasoning that, as there had been a full hearing in court, the failure to furnish an administrative hearing was cured.

U. S Supreme Court denies certiorari

Acanfora appealed the decision of the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals to the United States Supreme Court at its October Term, 1973. The Court thereafter denied certiorari, effectively upholding the lower court decision and refusing to reinstate Acanfora to his teaching position with Montgomery County Public Schools.

Life after the court cases

Acanfora never taught after he was not reinstated at Montgomery County Public Schools. Instead, he found work in Washington, D.C. and later moved to California. Once in California, Acanfora stayed within higher education, working at the University of California, in contract and grant administration and in patents and intellectual property management.[6] These days, Acanfora lives in Saigon with his husband, and they blog about their food experiences there.

References

- Acanfora vs. Montgomery County Public Schools, Maryland

- Bowman, Denise R. (June 15, 1972). "To Acanfora, it's the principle". The Pennsylvania Mirror. Box 4. Pennsylvania State University, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual Coalition Records. Eberly Family Special Collections Library, Penn State University Library, University Park, Pennsylvania. October 8, 2019.

- Acanfora, Leonore V. (August 9, 1972). "Letters to the editor: In defense of her son." The Collegian. Box 4. Pennsylvania State University, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual Coalition Records. Eberly Family Special Collections Library, Penn State University Library, University Park, Pennsylvania. October 8, 2019.

- Bowman, Denise R. (June 14, 1972). "6 PS deans to decide on Acanfora certification". The Pennsylvania Mirror. Eberly Family Special Collections Library, Penn State University Library. Box 4. Retrieved October 8, 2019 – via Pennsylvania State University, Lisbian, Gay, Bisexual Coalition Records.

- Shapiro, H.S. (August 23, 1972). "Homosexuals: Should they teach?". Chicago Tribune. ProQuest 169199104.

- Simpson, Craig (2012-12-20). "MoCo Gay Teacher Fired 1972; Justice Denied for 40 Years". Washington Area Spark. Retrieved 2019-10-08.

- Acanfora v. Board of Education of Montgomery County, 491 F.2d 498 (4th Cir. 1974).

- Acanfora v. Board of Education, 359 F. Supp. 843, 1973 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 13416 (United States District Court for the District of Maryland May 31, 1973 ). Retrieved from https://advance-lexis-com.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/api/document?collection=cases&id=urn:contentItem:3S4V-JMM0-003B-33WW-00000-00&context=1516831.

- "HOMOSEXUAL GAINS AUTHORITY TO TEACH". New York Times. Sep 24, 1972. p. 51 – via ProQuest.

- Walsh, Edward (13 April 1973). "Homosexual Teacher Fights to Return to Classroom". The Washington Post. p. C7 – via ProQuest.

- The Case of Joe Acanfora Webpage

- Penn State University Commission on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender Equity

- Queers Anonymous: Lesbians, Gay Men, Free Speech, and Cyberspace, Harvard Civil Rights – Civil Liberties Law Review, Vol 38, No. 1, Winter 2003 Copyright © 2003 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

- Section of Individual Rights and Responsibilities,American Bar Association Human Rights,Volume 24 Number 3 Summer 1997,Where Are the Civil Rights for Gay and Lesbian Teachers?

- Power, Prejudice, and the Right to Speak: Litigating "Outness" under the Equal Protection Clause Bobbi Bernstein, Stanford Law Review, Vol. 47, No. 2 (Jan., 1995), pp. 269-293 doi:10.2307/1229228

- DeLoggio Admissions Achievement Program, How Diversity is Measured : Sexual Orientation