Jindalee Operational Radar Network

The Jindalee Operational Radar Network (JORN) is an over-the-horizon radar (OTHR) network that can monitor air and sea movements across 37,000 km2. It has a normal operating range of 1,000 km to 3,000 km.[1] It is used in the defence of Australia, and can also monitor maritime operations, wave heights and wind directions.

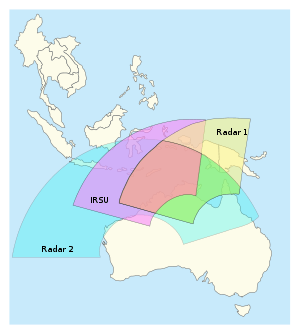

JORN's main ground stations comprise a control centre, known as the JORN Coordination Centre (JCC), at RAAF Base Edinburgh in South Australia and three transmission stations: Radar 1 near Longreach, Queensland, Radar 2 near Laverton, Western Australia and Radar 3 near Alice Springs, Northern Territory.[2]

History

The roots of the JORN can be traced back to post World War II experiments in the United States and a series of Australian experiments beginning in the early 1950s. From July 1970 a study was undertaken; this resulted in a proposal for a program to be carried out, in three phases, to develop an over-the-horizon-radar system.[3][4]

Geebung

Phase 1, Project Geebung, aimed to define operational requirements for an over-the-horizon-radar (OTHR), and study applicable technologies and techniques. The project carried out a series of ionospheric soundings evaluating the suitability of the ionosphere for the operation of an OTHR.[4]

Jindalee

Phase 2, Project Jindalee, aimed at proving the feasibility and costing of OTHR. This second phase was carried out by the Radar Division, (later, the High Frequency Radar Division), of the Defence Science and Technology Organisation (DSTO). Project Jindalee came into being during the period 1972–1974 and was divided into three stages.[4]

Stage 'A' commenced in April 1974. It involved the construction of a prototype radar receiver at Mount Everard, (near Alice Springs), a transmitter (at Harts Range, 160 km away) and a beacon in Derby. When completed (in October 1976) the Stage A radar ran for two years, closing in December 1978. Stage A formally ended in February 1979, having achieved its mission of proving the feasibility of OTHR.[4] The success of stage A resulted in the construction of a larger stage 'B' radar, drawing on the knowledge gained from stage A.

Stage 'B' commenced on 6 July 1978. The new radar was constructed next to the stage A radar. Developments during stage B included real time signal processing, custom built processors, larger antenna arrays, and higher power transmitters, which resulted in a more sensitive and capable radar.

- The first data was received by stage B in the period April–May 1982,

- the first ship was detected in January 1983, and

- an aircraft was automatically tracked in February 1984.

Trials were carried out with the Royal Australian Air Force during April 1984, substantially fulfilling the mission of stage B, to demonstrate an OTHR operating in Australia. Another two years of trials were carried out before the Jindalee project officially finished in December 1985.[4]

Stage 'C' became the conversion of the stage B radar to an operational radar. This stage saw substantial upgrades to the stage B equipment followed by the establishment of No. 1 Radar Surveillance Unit RAAF (1RSU) and the handover of the radar to 1RSU. The aim was to provide the Australian Defence Force with operational experience of OTHR.[2]

JORN

Phase 3

Phase 3 of the OTHR program was the design and construction of the JORN. The decision to build the JORN was announced in October 1986. Telstra, in association with GEC-Marconi, became the prime contractor and a fixed price contract for the construction of the JORN was signed on 11 June 1991. The JORN was to be completed by 13 June 1997.[2]

Phase 3 Project problems

Telstra was responsible for software development and systems integration, areas in which it had no previous experience. GEC-Marconi was responsible for the HF Radar and related software aspects of the project, areas in which it had no previous experience.[5] Other unsuccessful tenderers for the project included experienced Australian software development and systems integration company, BHP IT, and experienced Australian defence contractor AWA Defence Industries (AWADI). Both of these companies are no longer in business.[6]

By 1996, the project was experiencing technical difficulties and cost overruns.[2][7] Telstra reported an A$609 million loss and announced that it could not guarantee a delivery date.[8]

The failed Telstra contract prompted the project to enter a fourth phase.

Phase 4

Phase 4 involved the completion of the JORN and its subsequent maintenance using a new contractor. In February 1997 Lockheed Martin and Tenix received a contract to deliver and manage the JORN. Subsequently, during June 1997 Lockheed and Tenix formed the company RLM Group to handle the joint venture.[9] An operational radar system was delivered in April 2003, with maintenance contracted to continue until February 2007.[10]

In August 2008 Lockheed-Martin acquired Tenix Group's interest in RLM Holdings Pty Ltd.[11]

Phase 5

As a consequence of the duration of its construction, the JORN delivered in 2003 was designed to a specification developed in the early 1990s. During this period the Alice Springs radar had evolved significantly under the guidance of the Defence Science and Technology Organisation (DSTO). In February 2004 a fifth phase of the JORN project was approved.

Phase 5 aimed to upgrade the Laverton and Longreach radars to reflect over a decade of OTHR research and development. It was scheduled to run until approximately the year 2011,[10] but was completed around 2013/2014 due to skills shortage. All three stations are now similar, and use updated electronics.[12]

Phase 6

In March 2018 it was announced that BAE Systems Australia will undertake the $1.2 billion upgrade to Australia’s Jindalee Operational Radar Network which will take 10 years to complete.[13]

Project cost

The JORN project (JP2025) has had 5 phases,[14] and has cost approximately A$1.8 billion. The ANAO Audit report of June 1996 estimated an overall project cost for Phase 3 of $1.1 billion.[15] Phase 5 costs have been estimated at $70 million.[14] Phase 6 costs expect to be $1.2 billion.[13]

Network

JORN consists of:

- three active radar stations: one near Longreach, Queensland (Radar 1), a second near Laverton, Western Australia (Radar 2), and a third near Alice Springs, Northern Territory (Radar 3);

- a control centre at RAAF Base Edinburgh in South Australia (JCC);

- seven transponders; and

- twelve vertical ionosondes distributed around Australia and its territories.[2]

DSTO previously used the radar station near Alice Springs, Northern Territory (known as Jindalee Facility Alice Springs) for research and development[16] and also has its own network of vertical/oblique ionosondes for research purposes.[2][17][18] The Alice Springs radar was fully integrated into the JORN during Phase 5 to provide a third active radar station.[16]

Each radar station consists of a transmitter site and a receiver site, separated by a large distance to prevent the transmitter from interfering with the receiver. The JORN transmitter and receiver sites are:

- the Queensland transmitter at Longreach,[19] with 90-degree coverage (23.658047°S 144.145432°E, also on OzGeoRFMap),

- the Queensland receiver at Stonehenge,[19] with 90-degree coverage (24.291095°S 143.195286°E, also on OzGeoRFMap),

- the Western Australian transmitter at Leonora,[19] with 180-degree coverage (28.317378°S 122.843456°E, also on OzGeoRFMap), and

- the Western Australian receiver at Laverton, with 180-degree coverage (28.326747°S 122.005234°E, also on OzGeoRFMap).

- the Alice Springs transmitter at Harts Range,[19][20] with 90-degree coverage (22.967561°S 134.447937°E, also on OzGeoRFMap), and

- the Alice Springs receiver at Mount Everard,[19][20] with 90-degree coverage (23.521497°S 133.677521°E, also on OzGeoRFMap).

The Alice Springs radar was the original 'Jindalee Stage B' test bed on which the design of the other two stations was based. It continues to act as a research and development testbed in addition to its operational role.

The Mount Everard receiver site contains the remains of the first, smaller, 'Jindalee Stage A' receiver. It is visible in aerial photos, behind the stage B receiver (23.530074°S 133.68782°E). The stage A transmitter was rebuilt to become the stage B transmitter.[4]

The high frequency radio transmitter arrays at Longreach and Laverton have 28 elements, each driven by a 20-kilowatt power amplifier giving a total power of 560 kW.[2] Stage B transmitted 20 kW per amplifier.[2] The signal is bounced off the ionosphere, landing in the "illuminated" area of target interest. Much incident radiation is reflected forward in the original direction of travel, but a small proportion "backscatters" and returns along the original, reciprocal transmission path. These returns again reflect from the ionosphere, finally being received at the Longreach and Laverton stations. Signal attenuation, from transmit antenna to target and finally back to receive antenna, is substantial, and its performance in such a context marks this system as leading-edge science. The receiver stations use KEL Aerospace KFR35 series receivers.[16] JORN uses radio frequencies between 5 and 30 MHz,[21][22][23] which is far lower than most other civilian and military radars that operate in the microwave frequency band. Also, unlike most microwave radars, JORN does not use pulsed transmission, nor does it use movable antennas. Transmission is Frequency-Modulated Continuous Wave (FMCW), and the transmitted beam is aimed by the interaction between its "beam-steering" electronics and antenna characteristics in the transmit systems. Radar returns are distinguished in range by the offset between the instantaneous radiated signal frequency and the returning signal frequency. Returns are distinguished in azimuth by measuring phase offsets of individual returns incident across the kilometres-plus length of the multi-element receiving antenna array. Intensive computational work is necessary to JORN's operation, and refinement of the software suite offers the most cost-effective path for improvements.

The JORN ionosonde network is made up of vertical ionosondes, providing a real time map of the ionosphere. Each vertical incidence sounder (VIS) is a standardized Single-Receiver "Digisonde" Portable Sounder built by Lowell for the JORN. A new ionospheric map is generated every 225 seconds.[18] In a clockwise direction around Australia, the locations of the twelve (11 active and one test) JORN ionosondes are below.

The DSTO ionosonde network is not part of the JORN, but is used to further DSTO's research goals.[18] DSTO uses Four-Receiver Digisonde Portable Sounders (DPS-4), also built by Lowell.[2][17] During 2004 DSTO had ionosondes at the following locations.

- DSTO Ionosondes[17]

| Location | Coordinates | OzGeoRFMap |

|---|---|---|

| Wyndham, WA | 15.4°S 128.1°E | Wyndham, WA |

| Derby, WA | 17.3°S 123.6°E | Defence Site, DERBY |

| Darwin, NT | 12.5°S 130.9°E | 11 Mile IPS Site, BERRIMAH |

| Elliott near Newcastle Waters, NT | 17.6°S 133.5°E | Elliott near Newcastle Waters, NT |

| Alice Springs, NT | 24.0°S 133.8°E | Joint Space Defence Research Facility, ALICE SPRINGS |

From west to east, the seven JORN transponders are located at

- Christmas Island[2][16] (OzGeoRFMap),

- Broome, WA[2][24] (OzGeoRFMap),

- Kalumburu, WA[19] (OzGeoRFMap),

- Darwin, NT[2] (OzGeoRFMap),

- Nhulunbuy, NT[2][19] (OzGeoRFMap),

- Normanton, Qld[2][19] (OzGeoRFMap), and

- Horn island, Qld[2][19] (OzGeoRFMap).

All of the above sites (and many more that likely form part of the network) can be found precisely on the RadioFrequency Map,[25] which also lists the frequencies in use at each site.

Operation and uses

The JORN network is operated by No. 1 Remote Sensor Unit (1RSU). Data from the JORN sites is fed to the JORN Coordination Centre at RAAF Base Edinburgh where it is passed on to other agencies and military units. Officially the system allows the Australian Defence Force to observe air and sea activity north of Australia to distances up to 4000 km.[26] This encompasses all of Java, Irian Jaya, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, and may include Singapore.[27] However, in 1997, the prototype was able to detect missile launches by China[28] over 5,500 kilometres (3,400 mi) away.

JORN is so sensitive it is able to track planes as small as a Cessna 172 taking off and landing in East Timor 2600 km away. Current research is anticipated to increase its sensitivity by a factor of ten beyond this level.

It is also reportedly able to detect stealth aircraft, as typically these are designed only to avoid detection by microwave radar.[8] Project DUNDEE[29] was a cooperative research project, with American missile defence research, into using JORN to detect missiles.[30] The JORN was anticipated to play a role in future Missile Defense Agency initiatives, detecting and tracking missile launches in Asia.[31]

As JORN is reliant on the interaction of signals with the ionosphere ('bouncing'), disturbances in the ionosphere adversely affect performance. The most significant factor influencing this is solar changes, which include sunrise, sunset and solar disturbances. The effectiveness of JORN is also reduced by extreme weather, including lightning and rough seas.[32]

As JORN uses the Doppler principle to detect objects, it cannot detect objects moving at a tangent to the system, or objects moving at a similar speed to their surroundings.[32]

Theories regarding Malaysia Airlines Flight 370

In May 2016, the JORN FAQ file / Fact Sheet was updated by the RAAF to address questions about Malaysia Airlines Flight 370. According to the update, "JORN was not operational at the time of the aircraft's disappearance." The update also stated that MH370 would have been unlikely to be detected by the system due to radar range, ionospheric conditions and a "lack of information on MH370's possible flight path towards Australia."[33][34]

However, in the immediate aftermath of the 8 March 2014 disappearance, information regarding JORN's status was not released. This led to months of speculation. On 18 March 2014, sources cited by The Australian said that JORN was not tasked to look toward the Indian Ocean on the night of the disappearance of MH370 as there was no reason for it to be searching there at that time.[35] On 20 March 2014, it was reported that Malaysian Defence Minister (also Acting Transport Minister) Hishammuddin Hussein requested the US to give any information from the Pine Gap base near Alice Springs, possibly alluding to JORN as well.[36] On 19 March 2014, it was reported that an Australian Defence Department spokesman said it "won't be providing comment" regarding specific information on tracking MH370 by JORN.[37] However, several days prior to this, Australian Foreign Minister Julie Bishop told the Australian Parliament, "All our defence intelligence relating to Flight 370 has been, and will continue to be, passed on to Malaysian authorities..."[35][36]

In March 2015, before the July 2015 discovery of MH370 debris on Réunion Island, aviation technology expert Andre Milne requested information from JORN to prove or disprove that the aircraft ended up in the Indian Ocean,[38] but he received no response from the Australian government in 2015. It was made public in May 2016 that JORN was not operational at the time of the disappearance.[33]

Engineering heritage award

JORN received an Engineering Heritage International Marker from Engineers Australia as part of its Engineering Heritage Recognition Program.[39]

See also

- Imaging radar

- Cobra Mist

- Duga radar, a similar Russian system

References

- "Fact Sheet: Jindalee Operational Radar Network" (PDF). Royal Australian Air Force. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- Colegrove, Samuel B.(Bren) (2000). "Project Jindalee: From Bare Bones To Operational OTHR". IEEE International Radar Conference - Proceedings. IEEE. pp. 825–830. doi:10.1109/RADAR.2000.851942.

- "Project Arrangement between the Government of Australia and the Government of the United States of America on Data Fusion for Over-the-Horizon Radar ATS 29 of 1997" Archived 16 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Australasian Legal Information Institute, Australian Treaties Library. Retrieved on 15 April 2017.

- D.H. Sinnott (1988), "The Development of Over-the-Horizon Radar in Australia", DSTO Bicentennial History Series, Defence Science and Technology Organisation, Australian Department of Defence, 90, p. 16099, Bibcode:1989STIN...9016099S, ISBN 0-642-13561-4

- "Jindalee Over-the-Horizon Project (JORN) : Extract from a Channel 9 television program broadcast on 23rd March 1997". ourcivilisation.com. 23 March 1997. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- Natasha David (5 June 2000). "BHP IT purchase propels CSC to No. 2". Computerworld. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- McNally, Ray (18 August 1996). "Jindalee Operational Radar Network: Department of Defence" (PDF). The Auditor-General Performance Audit Audit Report No.28 1995–96. Australian National Audit Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 September 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2006.

- Sinclair-Jones, Michael (29 February 2000). "JORN assures early warning for Australia". Defence Systems Daily. Defence Data Ltd. Archived from the original on 16 November 2007. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- "RLM Group web site". Archived from the original on 23 August 2006.

- Thurston, Robin (21 June 2006). "Projects: JP 2025 - Jindalee Operational Radar Network (JORN)". Defence Materiel Organisation Website. Department of Defence. Archived from the original on 3 October 2006. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- "Lockheed Martin Completes Acquisition of Tenix Group's Interest in Australia-Based RLM Holdings". Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- Perrett, Bradley. "Australia’s Jindalee Radar System Gets Performance Boost" Aviation Week & Space Technology, 22 September 2014. Accessed: 24 September 2014. Archived on 24 September 2014

- Pyne, Christopher. "Boon for Australian defence industry as our JORN gets an upgrade". pyneonline.com.au. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Saun, Gary (15 July 2009). "JP 2025 - Jindalee Operational Radar Network (JORN)". Projects. Defence Materiel Organisation, Australian Department of Defence. Archived from the original on 3 October 2006. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- "Department of Defence : Jindalee Operational Radar Network : Performance Audit". Audit Report No. 28 1995–96 : Summary. Australian National Audit Office (ANAO). 18 June 1996. Archived from the original on 12 February 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- Wise, John C. (December 2004). "Summary of recent Australian radar developments". IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine. IEEE. 19 (4): 8–10. doi:10.1109/MAES.2004.1374061.

- "Digisonde Station List". University of Massachusetts Lowell, Center for Atmospheric Research. February 2004. Retrieved 29 November 2006.

- Gardiner-Garden, R.S. (February 2006). "Ionospheric variability in sounding data from JORN". Workshop on the Applications of Radio Science (WARS). Leura, NSW. Retrieved 29 November 2006.

- Hill, Senator Robert (12 May 2004). "Defence: Properties (Question No. 2685)" (PDF). Senate Official Hansard. No. Commonwealth of Australia. 6, 2004 (Fortieth Parliament, First Session–Eighth Period): 23144. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 September 2006. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- Erwin Chlanda, Nowhere To Hide When Alice's Radar Zeroes In, Alice Springs News, 28 April 2004

- "Specification: KPR35C1 HF Radar Receiver". KEL Aerospace website. KEL Aerospace. Retrieved 29 November 2006.

RF Input Frequency Range: 5 to 30 MHz

- "Specification: KPR35C2 HF Radar Receiver". KEL Aerospace website. KEL Aerospace. Retrieved 29 November 2006.

RF Input Frequency Range: 5 to 30 MHz

- "Specification: KPR35C3 HF Radar Receiver". KEL Aerospace website. KEL Aerospace. Retrieved 29 November 2006.

RF Input Frequency Range: 5 to 30 MHz

- Johnson, Ben A.; Dr. Yuri Abramovich (6–7 June 2006). "Detection-estimation of Gaussian sources for under-sampled training conditions: Practical HF OTHR application results" (PDF). Adaptive Sensor Array Processing (ASAP) Workshop. Lexington, Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Lincoln Laboratory. p. 24. Retrieved 29 November 2006.

- Australian Geographical RadioFrequency Map

- Styles, Barry (1998). "JORN HF Antenna Arrays Project Completed" (PDF). Stay Connected: The Radio Frequency Systems Bulletin. Radio Frequency Systems (RFS). pp. 11–12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2006.

RFS Australia proudly completes the USD25M Antenna Arrays for the Jindalee Operational Radar Network on time, on budget and within specification. Jindalee Over the Horizon Radar Network (JORN) is a High Frequency network that is designed to and sea radar coverage of up to 4,000 km from a large part of the Australian coastline.

- "Rough seas could have impeded boat detection: Analyst". ABC The World Today. 16 December 2010.

There's two layers if you like of radar surveillance. One is what's called the JORN system, which is a very, very long range strategic early warning system, that's capable of detecting targets as far away as, we think, Singapore.

- "Electronic Weapons". Strategy Page. StrategyWorld.com. 31 October 2004. Retrieved 21 November 2006.

In 1997, the prototype JORN system demonstrated the ability to detect and monitor missile launches by Chinese off the cost of Taiwan, and to pass that information onto U.S. Navy commanders.

- "Project DUNDEE". MISSILETHREAT.com. The Claremont Institute. 1 August 2004. Archived from the original on 23 December 2005. Retrieved 21 November 2006.

- U.S. And Australia Cooperate In Missile Detection, Missile Defense Agency Archived 1 March 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Nicholson, Brendan (7 January 2006). "Australia's key role in missile shield". The Age. Fairfax. Retrieved 18 November 2006.

- "Fact Sheet: Jindalee Operational Radar Network" (PDF). Royal Australian Air Force. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- "JORN FAQ" (PDF). airforce.gov.au.

- "Jindalee Operational Radar Network". airforce.gov.au.

- Stewart, Cameron (18 March 2014). "Malaysia Airlines flight MH370 'flew low to evade radars'". The Australian. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

sources say the system was not tasked to look westward towards the Indian Ocean on the morning of the MH370 flight because there was no reason to do so.

- Murdoch, Lindsay (20 March 2014). "Missing Malaysia Airlines plane: plea to US to release Pine Gap data". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- "Missing Malaysian plane: Why is Australia silent on secret radar data?". India Today. 19 March 2014.

- "Malaysia Airlines MH370: Aviation expert wants Australia to prove plane is in Indian Ocean". ibtimes.co.uk. 24 March 2015.

- "Jindalee Over-the-horizon Radar". Engineers Australia. Retrieved 2 May 2020.