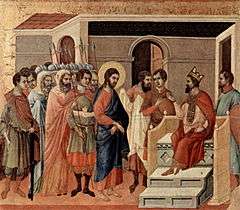

Jesus at Herod's court

Jesus at Herod's court refers to an episode in the New Testament which describes Jesus being sent to Herod Antipas in Jerusalem, prior to his crucifixion.[1] This episode is described in the Gospel of Luke (23:7–15).[2][3][4][5]

Biblical narrative

In the Gospel of Luke, after the Sanhedrin trial of Jesus, the Jewish elders ask Pontius Pilate to judge and condemn Jesus in 23:2, accusing Jesus of making false claims of being a king. While questioning Jesus about the claim of being the King of the Jews, Pilate realizes that Jesus is a Galilean and therefore under Herod's jurisdiction. Since Herod already happened to be in Jerusalem at that time, Pilate decides to send Jesus to Herod to be tried.[1][6]

Herod Antipas (the same man who had previously ordered the death of John the Baptist) had wanted to see Jesus for a long time, hoping to observe one of the miracles of Jesus.[6] However, Jesus says nothing in response to Herod's questions, or the vehement accusations of the chief priests and the scribes.

| Part of a series on |

| Christology |

|---|

Herod and his soldiers mock Jesus, put a gorgeous robe on him, as the King of the Jews, and send him back to Pilate. That day, Herod and Pilate, who had previously been enemies, become friends.[7][1]

| Events in the |

| Life of Jesus according to the canonical gospels |

|---|

|

|

In rest of the NT |

|

Portals: |

The Gospel of Luke does not state that Herod did not condemn Jesus, and instead attributes that conclusion to Pilate who then calls together the Jewish elders, and says to them:[6]

"I having examined him before you, found no fault in this man touching those things whereof ye accuse him: no, nor yet Herod: for he sent him back unto us; and behold, nothing worthy of death hath been done by him."[8]

After further conversations between Pilate and the Jewish elders, Jesus is sent to be crucified on Calvary.[1]

Christology

This statement by Pilate that Herod found no fault in Jesus is the second of the three declarations he makes about the innocence of Jesus in Luke's Gospel, (the first being in 23:4 and the third in 23:22) and builds on the "Christology of innocence" present in that Gospel.[9][10][11] In the narrative that follows this episode, other people beside Pilate and Herod also find no fault in Jesus.[10] In 23:41 one of the two thieves crucified next to Jesus also states Jesus' innocence, while in 23:47 the Roman centurion says: "Certainly this was a righteous man."[11][10] The centurion's characterization illustrates the Christological focus of Luke on innocence (which started in the courts of Pilate and Herod), in contrast to Matthew 27:54 and Mark 15:39 in which the centurion states: "Truly this man was the Son of God", emphasizing Jesus' divinity.[11]

John Calvin considered the lack of response from Jesus to the questions posed by Herod, his silence in the face of the accusations made by the Jewish elders, and the minimal conversation with Pilate after his return from Herod as an element of the "agent Christology" of the crucifixion.[12][13] Calvin stated that Jesus could have argued for his innocence, but instead remained mostly quiet and willingly submitted to his crucifixion in obedience to the will of the Father, for he knew his role as the "willing Lamb of God".[12][13] The "agent Christology" reinforced in Herod's court builds on the prediction by Jesus in Luke 18:32 that he shall be: "delivered up unto the Gentiles, and shall be mocked, and shamefully treated."[11] In Herod's court, Luke continues to emphasize Jesus' role not as an "unwilling sacrifice" but as a willing "agent and servant" of God who submitted to the will of the Father.[14][11]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jesus Christ before Herod. |

- Chronology of Jesus

- Pilate's court

- Passion (Christianity)

References

- New Testament History by Richard L. Niswonger 1992 ISBN 0-310-31201-9 page 172

- The Synoptics: Matthew, Mark, Luke by Ján Majerník, Joseph Ponessa 2005 ISBN 1-931018-31-6 page 181

- The Gospel according to Luke by Michael Patella 2005 ISBN 0-8146-2862-1 page 16

- Luke: The Gospel of Amazement by Michael Card 2011 ISBN 978-0-8308-3835-6 page 251

- "Bible Study Workshop - Lesson 228" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2011-04-06.

- Pontius Pilate: portraits of a Roman governor by Warren Carter 2003 ISBN 978-0-8146-5113-1 pages 120-121

- Luke 23:12

- Luke 23:13–15

- The character and purpose of Luke's christology by Douglas Buckwalter 1996 ISBN 0-521-56180-9 pages 109-111

- Early narrative Christology: the Lord in the Gospel of Luke by Christopher Kavin Rowe 2006 ISBN 3-11-018995-X page 183

- Luke's presentation of Jesus: a christology by Robert F. O'Toole 2004 ISBN 88-7653-625-6 pages 96-101

- The Reading and Preaching of the Scriptures by Hughes Oliphant Old 2002 ISBN 0-8028-4775-7 page 125

- Calvin's Christology by Stephen Edmondson 2004 ISBN 0-521-54154-9 page 91

- Holiness and ecclesiology in the New Testament by Kent E. Brower, Andy Johnson 2007 ISBN 0-8028-4560-6 page 115