Jerome War Relocation Center

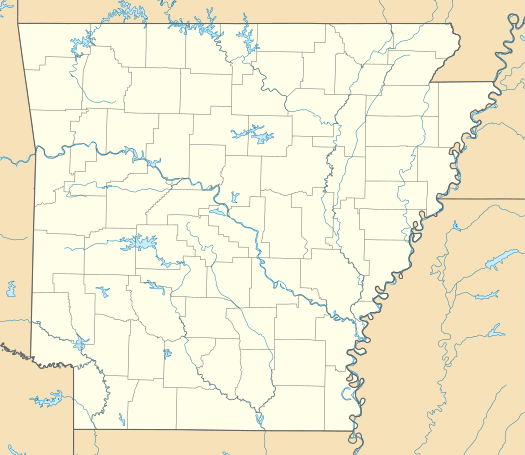

The Jerome War Relocation Center was a Japanese American internment camp located in southeastern Arkansas, near the town of Jerome in the Arkansas Delta. Open from October 6, 1942, until June 30, 1944, it was the last American concentration camp to open and the first to close. At one point it held as many as 8,497 detainees.[1][2] After closing, it was converted into a holding camp for German prisoners of war.[1] Today, few remains of the camp are visible, as the wooden buildings were taken down. The smokestack from the hospital incinerator still stands.

Jerome War Relocation Center | |

|---|---|

Detainee camp | |

.jpg) Jerome War Relocation Center, 1942 | |

Jerome War Relocation Center Location of the camp in the state of Arkansas | |

| Coordinates: 33°24′42″N 91°27′40″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Arkansas |

| Opened | 1942 |

| Closed | 1944 |

| Founded by | War Relocation Authority |

| Population (February 1943) | |

| • Total | 8,497 |

Jerome is located 30 miles (48.3 km) southwest of the Rohwer War Relocation Center,[1] also in the Delta. Due to the large number of Japanese Americans detained there, these two camps were briefly ranked as the fifth- and sixth-largest towns in Arkansas. Both camps were served by the same rail line.

A 10-foot (3.0 m) high granite monument marks the camp location and history. The marker is located on US Highway 165, at County Road 210, approximately 8 miles south of Dermott, Arkansas.

On December 21, 2006, President George W. Bush signed H.R. 1492 into law authorizing $38,000,000 in federal money to preserve the Jerome relocation center, along with nine other former Japanese internment camps.[3]

The PBS documentary film Time of Fear explores the history of these two American concentration camps in Arkansas.

History of the camp

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 brought the United States into World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was lobbied to sign Executive Order 9066, which authorized military leaders to declare the West Coast a military zone from which persons considered "a threat to security" could be excluded. Some military leaders opposed this action, and historians have concluded that the order was based largely on local exaggerated fears and xenophobia, plus economic competition. Officials classified most Japanese Americans as potential threats, including native-born citizens. They forced the "evacuation" of 120,000 Japanese Americans; whole families were rounded up and deported to concentration camps newly constructed in isolated areas of the country's interior.

The Jerome War Relocation Camp was located in Southeast Arkansas in Chicot and Drew counties. It was one of two American concentration camps in the Arkansas Delta, the other being at Rohwer, 27 miles (43 km) north of Jerome. The Jerome site was situated on 10,054 acres (4,069 ha) of tax-delinquent land in the marshy delta of the Mississippi River's flood plain, which had been purchased in the 1930s during Depression relief efforts by the Farm Security Administration. Despite initial resistance from Governor Homer Adkins – who agreed to allow the camps only after exacting a federal guarantee that the Japanese American inmates would be watched by armed white guards and removed from the state at the end of the war – the War Relocation Authority acquired the land in 1942.[2] Along with other Southern states, Arkansas had legal racial segregation and Jim Crow laws; they had already disenfranchised most African Americans in the state at the turn of the century.

The A. J. Rife Construction Company of Dallas, Texas, working under the supervision of the Army Corps of Engineers, built the Jerome camp at a cost of $4,703,347. The architect, Edward F. Neild of Shreveport, Louisiana, also designed the camp at Rohwer in Desha County.[4]

Jerome was divided into 50 blocks, which were surrounded by a barbed wire fence, a patrol road, and seven watchtowers. Administrative and community spaces such as schools, offices and the hospital were separate from the 36 residential or barracks blocks. These consisted of twelve barracks divided into several "apartments", in addition to communal dining and sanitary facilities. Approximately 250 to 300 individuals lived in each block.[2] The only entrances were from the main highway on the west and at the back of the camp to the east. The camp was not finished when its first inmates began to arrive from California assembly centers. These early arrivals were forced to work on construction of their incarceration quarters.[2]

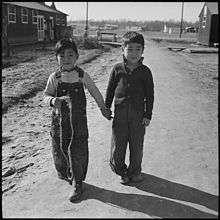

This was the last center to open and the first to close; it operated for 634 days – the fewest of any of the American concentration camps. The constant movement of camp populations into and out of facilities has made accurate statistics difficult. As of January 1943, the camp had a population of 7,932 people, and the following month Jerome reached its peak at nearly 8,500. Most prisoners had lived in Los Angeles or farmed in and around Fresno and Sacramento before the war, but some ten percent of Jerome's population was relocated from Hawai'i.[2] Fourteen percent were over the age of sixty, and there were 2,483 school-age children in the camp, thirty-one percent of the total population. Thirty-nine percent of the residents were under the age of nineteen. Sixty-six percent were American citizens, having been born in the United States, and were known as Nisei. The Issei, or first-generation, immigrant parents and grandparents had been prohibited by US law from obtaining citizenship, along with other East Asians, were officially referred to as "aliens".

The camp was closed at the end of June 1944 and adapted as a German prisoner-of-war camp, renamed as Camp Dermott. Due to questions about their loyalty due to answers to the confusing loyalty questionnaire, many Japanese American male inmates had already been transferred to the Tule Lake segregation camp in California. The remainder of the prisoners were sent to Rohwer in Arkansas and the Gila River War Relocation Center in Arizona, constructed on the Pima/Maricopa reservation.[2]

Camp life and social clubs

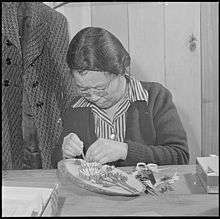

Adult camp residents worked at farming, the saw mill, or making soap. The barracks were small and poorly insulated. Sometimes several families had to share a one-room "apartment", which did not provide enough room for even one family. Project Director Paul A. Taylor warned residents that leaving the camp without permission and trespassing on private property were punishable offenses.

Having thousands of people living in such dense quarters increased their risk of disease. In January 1944, influenza spread throughout the camp for several months. The hospital at Jerome was acknowledged as the best equipped and best staffed of any WRA center, and provided enough medical assistance to alleviate most health problems.

The residents of the camp were resourceful, forming social and culture clubs. The Jovial Peppers was a group of girls, ages 9 to 12. The Phi Beta Society consisted of a group of young women whose main purpose was to improve their cultural background. Other clubs included Cub Scouts and the Double X's. Recreation and sports were very popular. Sports consisted of basketball, weightlifting, boxing, wrestling, and volleyball. Basketball drew the most attention from sports lovers. In one match noted as an "annihilation", the Shamrocks defeated the Commandos 19-2. Frank Horiuchi got credit for the lone basket on the losing side.

Art classes and piano lessons were offered. Adult education classes included English, sewing, drafting, flower arrangement, commercial law, photography and art. Dances and movies were frequently available.

Resistance to military enlistment and the loyalty questionnaire

As at the other WRA camps, many of the Nisei (second-generation, American-born) young men were recruited to volunteer for the armed forces. All adults were required to submit to an assessment of their loyalty to the United States. Pressure to join the all-Nisei 442nd Regimental Combat Team was somewhat higher at Jerome and Rohwer, which were much closer to the unit's training facilities at Camp Shelby, Mississippi. These camps became popular destinations for 442nd soldiers on leave. Col. Scobey, executive to the Assistant Secretary of War, visited Jerome on March 4, 1943 to persuade eligible internees to enlist in the 442nd. He said that the War Department was in effect presenting the 442nd as a test of loyalty, and if few men signed up, the public would believe the Nisei were not loyal Americans. Eventually, 515 men [5] volunteered or were conscripted for the legendary 100th Infantry Battalion[6], the famed 442nd RCT[7], and the MIS.[8]

The so-called "loyalty questionnaire" met with resistance in Jerome (and elsewhere) largely because of the last two questions. They were poorly worded, and made insulting assumptions. Some men whose English was more limited had trouble interpreting them; other understood enough to be offended. One question asked if US-born men would be willing to serve in the military. The second asked all respondents if they "would disavow their allegiance to Japan", but most had no allegiance to that country. Many were confused by the questions' wording, unsure if an affirmative answer to the second would be taken as an admission of previous disloyalty and a threat to their families. Others, especially among the citizen Nisei, were offended by the implication that they were somehow un-American yet ought to fight to risk their lives for a country that had imprisoned them and overridden their rights.[9]

Due to an earlier dispute with administration over working conditions in Jerome and the death of an inmate in an on-the-job accident, tensions in camp were already high. In separate incidents on March 6, 1943, two men seen as administration collaborators were beaten by inmates. Jerome inmates subsequently gave negative or qualified responses to the question regarding Japanese allegiance at a rate higher than at any other WRA camp.[2]

Mitsuho Kimura was one of six members of a committee of inmates who conferred with Director Paul Taylor and said that they would protest the WRA's Evacuee Registration Program (the official name of the loyalty assessment program). Kimura, who was born in Hawai'i in 1919 and attended high school in Japan from 1932 to 1935 before returning to the U.S. territory, was described by a Naval Intelligence informant as a "very dangerous type of individual." He said that he was loyal to Japan before Pearl Harbor, and that his loyalty to Japan had increased after Pearl Harbor. He asserted that he would not fight in the U.S. Army under any conditions, but would readily fight in the Japanese Army against the United States. He organized group meetings at Jerome with other pro-Japanese inmates. The committee refused to register because they were loyal to Japan. 781 evacuees in the group registered by writing across the face of the registration form that they wanted to be repatriated or expatriated to Japan.

Leave clearance at Jerome

Camp residents were allowed to leave the camp with permission in order to take jobs on the outside. However, many did not want to leave without the guarantees of food and a place to stay provided by the camp. Another drawback to was that the process of getting a leave clearance was slow, causing some to lose interest. The draft and registration processes also complicated getting a leave clearance.

Camp closing

The Jerome Relocation Camp closed on 30 June 1944 and was converted into a holding camp for German prisoners of war. According to U-boat commander Hein Fehler of U-234 food allocation at the camp while he was there was very poor.[10] Today there are few remains of the camp standing, the most prominent being the smokestack from the hospital incinerator. A 10 foot high granite monument marks the camp location and gives details of its history.

The Jerome Relocation Center operated for a total of 634 days, the least of any of the American concentration camps. Riots and isolated confrontations erupted in response to administration of the loyalty questionnaire. But the Denson Tribune reported on June 11, 1944 that the "camp was free from juvenile delinquency (...) young girls and boys are well-behaved, well disciplined, well-trained, well-taught, and well led. Rowdyism, pranks, swearing, petty theft and juvenile vices are practically nil." There were no reports of vandalism. This contrasts with poorer results in some of the other camps.

Once the camp was closed, the remaining residents were transferred. Heart Mountain received 507 residents, Gila River received 2,055, Granada received 514, and Rohwer received 2,522.

Notable Jerome internees

- Violet Kazue de Cristoforo (1917–2007), a Japanese American poet. Also interned at Tule Lake

- Takayo Fischer (born 1932), an American stage, film and TV actress. Also interned at Rohwer

- Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga (1925–2018), political activist. Also interned at Manzanar and Rohwer

- George Hoshida (1907–1985), a Japanese American artist who made drawings of his experience during his incarceration in three internment camps. Also interned at Gila River

- Lawson Fusao Inada (born 1938), an American poet. Also interned at Granada

- Yuri Kochiyama (1921–2014), a Japanese American human rights activist

- Roy Matsumoto (1914–2014), a United States Army soldier and inductee of the U.S. Army Rangers Hall Of Fame and the Military Intelligence Corps Hall of Fame

- Horace Yomishi Mochizuki (1937–1989), a mathematician

- George Nakano (born 1935), a former California State Assemblyman

- Joe M. Nishimoto (1919–1944), a United States Army soldier and a recipient of the Medal of Honor

- Otokichi Ozaki (1904-–1983), a Japanese poet

- Henry Sugimoto (1900–1990), Japanese-born artist. Also interned at Rohwer

- Mary Tsukamoto (1915–1998),a teacher, community activist, and civil rights activist

- V. Vale (born 1942), publisher, author, musician

- Conrad Yama (born Kiyoshi Conrad Hamanaka) (1919–2010), a theatre, film, and television actor

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jerome War Relocation Center. |

References

- Japanese American Internment Sites Preservation "Japanese American Internment Sites Preservation" Archived 2009-01-06 at the Wayback Machine, a report from the National Park Service.

- Niiya, Brian. "Jerome Archived 2014-05-23 at the Wayback Machine," Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- "H.R. 1492". Archived from the original on 2017-09-26. Retrieved 2017-09-01.

- "Neild, Edward F." lahisatory.org. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- https://www.dropbox.com/sh/2nihl23t9tg7uxv/AAAUYc2PkAR72q99FMxy7jGfa/14)%20SOLDIERS%20AND%20CAMPS?dl=0&preview=!SOLDIERS+AND+THE+CAMPS+(Alphabetical)+646B.pdf&subfolder_nav_tracking=1

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-09-09. Retrieved 2019-11-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-12-20. Retrieved 2019-11-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-12-18. Retrieved 2019-11-23.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Lyon, Cherstin M. "Loyalty questionnaire Archived 2014-06-22 at the Wayback Machine," Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- A. V. Sellwood The Warring Seas, Universal-Tandem Publishing 1972 pp. 213-18

Further reading

- Bearden, Russell. "Life inside Arkansas: Japanese American Relocation Centers". Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 48. 1989 169-196.

- Burton, Jeffrey F.; Farrell, Mary M.; Lord, Florence B.; Lord, Richard W. Confinement and Ethnicity An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites. Tucson, Arizona: Western Archeological and Conservation Center, 1999. 149-160.

- Friedlander, E.J. "Freedom of Press behind Barbed Wire: Paul Yokota and the Jerome Relocation Center Newspaper". Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 44. 1985: 303-313.

- Howard, John. "John Yoshido in Arkansas, 1943." Southern Spaces, 2 October 2008.

- Kim, Kristine. Henry Sugimoto: Painting an American Experience. Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2000.

- McVoy, Edgar C. "Social Process in the War Relocation Center". Social Forces, 22. December 1943: 188-190.

- Niiya, Brian. "Jerome," Densho Encyclopedia, 2014.

- Tsukamoto, Mary and Pinkerton, Elizabeth. We the People: A Story of Internment in America. San Jose: Laguna Publishers, 1987.

- Wakida, Patricia. "Denson Tribune (newspaper)," 2014.