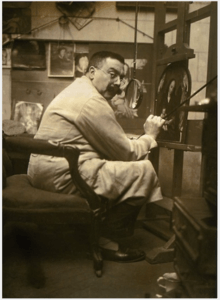

Jef Van der Veken

Jef Van der Veken (official name: Josephus Maria Vander Veken)[1][2] (1872 in Antwerp – 1964 in Ixelles) was a Belgian art restorer, copyist and art forger, who had mastered the art of reproducing the works of the Early Netherlandish painters.

Early life

Jef Van der Veken's parents operated a crystal and porcelain ware business in Antwerp. From a young age Jef Van der Veken nourished artistic ambitions. While performing his compulsory military service, he attended drawing classes at the Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp. Here he learned the art of painting by copying photographs and making free adaptations of the old masters. He completed his academic training at the top of his class. Van der Veken then started to make pastiches on order and established himself as an antique dealer in Brussels in 1908.[3] He became so skilled in mimicking the style of the old masters that his works were taken for originals and some were even sold as such. For instance, at the 1927 London exhibition on Flemish and Belgian Art between 1300-1900 a work by his hand was exhibited as an original old master. Van der Veken had to convince the organizers to remove the painting that he had made on the basis of a badly damaged original. This incident caused quite a scandal in the press and scientific literature of the time.

The start of the First World War marked a change in his professional and artistic career as Van der Veken shifted his interest to restoration work and perfected his own restoration process, the "hyperrestauration". This process consisted in the recovery of an old, damaged or modest work, which served as the support for a new creation. He was passionate about the Flemish Primitives, particularly Rogier van der Weyden and Jan van Eyck, and prided himself on having rediscovered the technique of painting with eggs which according to him had been used by early Netherlandish painters. It has been demonstrated since that the basis of the technique of early Netherlandish painters was not the use of eggs but the use of oil-based paint.[3]

Association with Renders

Van der Veken's association with Émile Renders started in the early 1920s. Renders was a wealthy banker and mecenas from Bruges who had the necessary funds to buy damaged or modest works which he asked Van der Veken to restore through the hyperrestoration process. Van der Veken restored 16 paintings acquired by Renders using this method. The works restored by Van der Veken thus accounted for an important portion of the collection of old masters that Renders built up and which was referred to as the Renders Collection. The Renders Collection came to be regarded as one of the principal private collections of Early Netherlandish paintings and had a prominent place in the 1927 London exhibition of Flemish old masters.

On the strength of the reputation of his collection, Renders profiled himself as an informed connoisseur of Flemish old masters. He published studies in which he cast doubt on the existence of Hubert van Eyck and identified the Master of Flémalle with Rogier van der Weyden (current scholarship identifies the Master of Flémalle with Robert Campin, the teacher of Rogier van der Weyden). These publications aroused lively polemics with reputed art historians.

At the 1935 World Exhibition in Brussels three works, of which the visible surface had been executed mainly by Van der Veken, where exhibited under the name of Rogier van der Weyden: one as an original work by van der Weyden (the Madonna with Child or 'Renders Madonna', now in the Museum of Fine Arts in Tournai) and two as works by van der Weyden's workshop.[4]

Recognition as restorer

Van der Veken's reputation as a restorer was such that internationally renowned art historians Leo van Puyvelde and Georges Hulin de Loo recommended him to the Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium.[5] He worked there for many years as a restorer using methods of restoration that were less controversial and more in line with contemporary ideas and insights in the field of restoration. He was soon recognized as a renowned expert and was invited to take on the restoration of the finest panels of Hans Memling held by the Old St. John's Hospital and the Groeningemuseum in Bruges. Van der Veken considered his restoration of Jan van Eyck's Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele in 1934 as his most honorable commission.[3]

Copy of the Just Judges

In 1934 the panel of The Just Judges, which formed the lower left panel of the Ghent Altarpiece, by Jan van Eyck or his brother Hubert Van Eyck was stolen and had not been recovered. Van der Veken decided in 1939 to make a copy of the panel using a two centuries old closet shelf as the support. He made the copy of the missing painting on the basis of a copy that Michiel Coxie (1499-1592) had produced in the mid-sixteenth century for Philip II of Spain and was kept at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium. He interrupted his work during the Second World War and resumed work in 1945, this time in the Saint Bavo Cathedral in Ghent where the Ghent Altarpiece had been moved to the Vijdtkapel. In order to harmonize his copy with the appearance of the other panels of the Ghent Altarpiece he applied a layer of wax to create a similar patina. Van der Veken subtly indicated that his work was a copy by giving one of the horsemen the facial features of the then Belgian king Leopold III.

The local authority in charge of managing religious property, called the 'Kerkfabriek', had become interested in acquiring the copy to replace the stolen panel. The Kerkfabriek and Van der Veken were initially not able to agree on the fee payable. Van der Veken asked 300,000 Belgian francs for his work - a large sum in those days - but the Kerkfabriek did not agree to pay this fee. In the end after much discussion, an agreement was reached in 1957: the Kerkfabriek would pay 75,000 francs, the Belgian State 150,000 francs.

Following Van der Veken's completion of the copy, there have been persistent rumours that the original of the work lies beneath his copy. Undeniably, the high quality of the copy plays a major role in this remarkable assertion. Technical research has shown that the copy was made out on a wooden carrier, which is entirely unrelated to that of the original.[6]

Legacy

Van der Veken continued to work for the Central Laboratory of the Museums of Belgium after the Second World War. Despite the onset of blindness he remained active until the end of his life, and his son-in-law, Albert Philippot, who had been trained by Van der Veken, gradually took over his restoration tasks. It is Albert Philippot who commenced the restoration of the Ghent Altarpiece in 1950.[7]

Controversies surrounding the Renders Collection

While during the Second World War Van der Veken continued his restoration work for the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Renders took the opportunity to sell the 20 early Netherlandish paintings in the Renders Collection, including the hyperrestored works on which Van der Veken had worked, to the German Nazi leader Hermann Göring for the price of 300 kilograms of gold.[4]

After the war, the Belgian state claimed the 20 works back as looted art. Only half of the works were recovered. Renders commenced judicial proceedings against the Belgian state claiming that he had never been paid for the paintings. The truth was, however, revealed when letters were discovered in the archive of Goering that showed that Renders had negotiated with Goering on the sale of his Gothic sculptures.[4]

More controversy and accusations of forgery

The role played by Renders as an art collector and his relationship with Jef Van der Veken were finally questioned at the end of the 20th century. The discussion was initiated as a result of studies on three of the paintings that had belonged to the Renders Collection, had been sold to Goering and were subjected to modern scientific research decades after the war. The paintings are referred to as the Renders Magdalena, the Renders Madonna and the Renders Man of Sorrows.

The Renders Magdalena

The Renders Magdalena is a portrait of Mary Magdalene, that was claimed to be a copy of the right panel of the Braque Triptych by Rogier van der Weyden, the original of which hangs in The Louvre. The Renders Magdalena started as a bad old copy, which was acquired by a collector in Antwerp around 1885 and then bequeathed to the museum of Ghent in 1914. The museum refused the painting because of its mediocrity and put it up for sale in Ghent in 1920. It was bought by an antique dealer in Dendermonde from whom Renders acquired it.[4] Renders asked Van der Veken to restore the painting. When the painting reappeared 6 years later at an exhibition in Bern, the painting had been drastically changed. What had appeared a mediocre copy had become a masterpiece that was attributed to the entourage of Hans Memling.[3] However, not all contemporary art experts were impressed by this metamorphosis and they raised doubts about the work's authenticity.[7]

Acquired by Goering from Renders, the panel was brought to Spain by Alois Miedl, an agent of Goering, after World War II. In 1966 he sold the panel to a Scandinavian collector. When the collector died, his heirs wanted to have an expert opinion on its value and in 2004 they sent the panel to the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage in Brussels.

Based on its research findings, the Institute concluded that the painting was painted on top of an older painting, which had been scraped off to the preparation layer. The institute also found that modern paints had been used in the restoration and that the restorer had made new underdrawings and used various techniques to recreate the craquelure of the painting.[3] The institute also discovered that Van der Veken had made some minor changes to the back of the panel, probably in an attempt to make the work appear more similar to the original van der Weyden and increase its appearance of authenticity. All of these interventions by Van der Veken can be qualified as amounting to an intention to create a forgery.[7]

The Renders Magdalena was not returned to the owners as it was claimed by the Belgian state.

The Renders Madonna

.jpg)

The second controversy involves the Renders Madonna which Renders had sold to Goering and after its return to Belgium has been part of the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts of Tournai where it is attributed to the 'School of Rogier van der Weyden'.

Originally, the Renders Madonna panel had been part of a diptych attributed to Rogier van der Weyden. The other half is a portrait of the donor Jean Gros, which has been located in the Art Institute Chicago since 1933.[8] The diptych was probably separated in 1867, the year in which the portrait of Jean Gros was shown at an exhibition in Bruges, organized by the historian James Weale. It was probably the deplorable material condition of the Madonna which led to the decision to separate the two panels of the diptych. A German photo from World War I shows the battered state of the panel at that time.[5]

When he was asked by Renders to restore the Madonna, Van der Veken endeavored to reconstruct all that had been irretrievably lost and damaged. He used his very 'radical' hyperrestoration method. His intervention still determines the present condition of the painting and there is no visible aging. The 'restoration' cannot be detected with the naked eye by a trained observer who knows what he is looking for.

Research carried out in 1999-2000 by the Laboratoire d’étude des oeuvres d’art par les méthodes scientifiques (Laboratory for the scientific examination of art works) of the Université Catholique de Louvain made it possible to determine the extent of the restoration and to describe the restoration process in detail. The research showed that Van der Veken had literally scraped off the bottom part of the painting, thereby removing the original painting in that area. He must have felt that it would be more efficient to start over than to preserve the remaining original paint residue. He proceeded in the same manner in other areas of the painting, especially in the image of the Child, where he entirely repainted the lower part of the face and shoulders. Van der Veken also painted several areas with new paint probably because they were worn. In addition, he painted over entire surfaces, rather than execute multiple, small retouches to integrate the whole picture. Like in the restoration of the Renders Magdalena, he again mimicked the craquelure through various methods. Radiographic recording showed how little is left of the original paint layers.

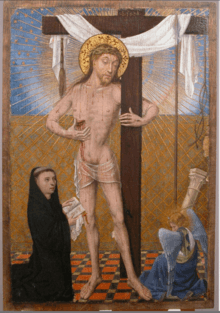

The Renders Man of Sorrows

Another painting of the Renders Collection, a 15th-century Man of Sorrows owned by the Metropolitan Museum in New York was submitted to testing in 1992. It had already been relegated to the Museum's storage in 1974 after experts from the Courtauld Institute of Art deemed it to be a completely modern forgery. The 1992 tests came to the conclusion that the painting was based on an original painting of the second half of the 15th century to which a later restorer deceptively had added new elements such as the background and the figure of the angel. The suspicion is that this restorer was Jef Van der Veken.[9]

Conclusion

The conclusion of the recent scientific findings is that both Van der Veken and Renders appear to have engaged in intentional art forgery. Since these revelations, all the works that had belonged to the Renders Collection or had been handled by Van der Veken and even his son-in-law Albert Philippot, many of which hang in major museums in Belgium and abroad, are viewed with suspicion.[10]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jef Van der Veken. |

- Biographical details at the Netherlands Institute for Art History (in Dutch)

- Alternative name spellings and name variations: Jef Vanderveken, Jef van der Veken, Josephus Maria Vander Veken, Josephus Maria Vander Veken, Joseph-Marie Van der Veken, Joseph Van der Veken, Joseph van der Veken

- Persdossier Autour de la "Madeleine Renders" at the Koninklijk Instituut voor het Kunstpatrimonium (in Dutch)

- L’affaire Van der Veken at the Koninklijk Instituut voor het Kunstpatrimonium (in French)

- Fake - not fake: restorations-reconstructions-forgeries: the conservation of the Flemish Primitives in Belgium, ca. 1930-1950 on CODART (in Dutch)

- Rudi Schrever, ‘Rechtvaardige Rechters’ van het Lam Gods onder handen genomen, in: Historiek, 22 June 2010

- Jacques Foucart, Autour de la "Madeleine Renders", 25 February 2011

- Rogier van der Weyden and Workshop Netherlandish, c. 1399–1464, Portrait of Jean Gros, 1460/64, at the Art Institute Chicago

- Hubert von Sonnenburg, A Case of Recurring Deception

- De relatie opdrachtgever – restaurateur Archived 16 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine (in Dutch)