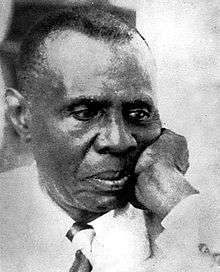

Jean Price-Mars

Jean Price-Mars (15 October 1876 – 1 March 1969) was a Haitian doctor, teacher, politician, diplomat, writer, and ethnographer.[1] Price-Mars served as secretary of the Haitian legation in Washington, D.C. (1909) and as chargé d'affaires in Paris (1915–1917), during the initial years of the United States occupation of Haiti.

Jean Price-Mars | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs and Worship | |

| In office 14 December 1956 – 9 February 1957 | |

| President | Joseph Nemours Pierre-Louis |

| Preceded by | Joseph D. Charles |

| Succeeded by | Evremont Carrié |

| Minister for Foreign Affairs, Worship and Education | |

| In office 19 August 1946 – 10 April 1947 | |

| President | Dumarsais Estimé |

| Preceded by | Antoine Levelt (Foreign Affairs and Worship) Daniel Fignolé (Education) |

| Succeeded by | Edmée Manigat (Foreign Affairs and Worship) Emile Saint-Lot (Education) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 15, 1876 Grande-Rivière-du-Nord |

| Died | March 1, 1969 (aged 92) Pétion-Ville |

In 1922, Price-Mars completed medical studies which he had given up for lack of a scholarship.[1]

After withdrawing as a candidate for the presidency of Haiti in favor of Stenio Vincent in 1930, Price-Mars led Senate opposition to the new president; he was forced out of politics. In 1941, Price-Mars was again elected to the Senate. He was secretary of state for external relations in 1946 and, later, ambassador to the Dominican Republic. In his eighties, he continued service as Haitian ambassador at the United Nations and ambassador to France.

Négritude movement

Price-Mars championed Négritude in Haiti through his writing, which "discovered" and embraced the African roots of Haitian society. Price-Mars was the first prominent defender of vodou as a full religion complete with "deities, a priesthood, a theology, and morality."[2] He argued against the prevailing prejudice and ideology which favored European cultures from the colonial period and rejected non-white, non-Western, elements of the cultures of the Americas. His nationalism embraced a Haitian cultural identity as African through slavery.

Price-Mars' attitude was inspired by the active resistance by Haitian peasants to the 1915 through 1934 United States occupation. He deplored the elite's abandonment of the tradition that had emphasized the nation's achieving independence from French colonialism, but he took pride in the conduct of the poor. He attacked the elite for their "inability to promote the welfare of the Haitian masses."[3]

Collective bovarysme

He coined the term collective bovarysme to describe the elite as identifying with their partial European ancestry while denouncing ties to their African legacy[2] (in Gustave Flaubert's novel Madame Bovary, Emma Bovary is anxious to escape from social conditions which define her, but which she deprecates). He noticed that the elite were composed almost exclusively of people of mixed ancestry, descended from former free persons of color, who embraced their "whiteness." Most Haitians were more exclusively African in descent. His disdain for the elites spread beyond their racial purity of "bovarysme".

He believed they had unfair economic and political influence. He understood that their power base in the state system relied heavily on the taxation of crops, especially of coffee, the chief export, grown by the peasants who had come to the country's defense when the elites had abandoned it to protect their own interests.

He also attacked the elites' role in Haitian education. The elite believed they needed to civilize the masses. Price-Mars wrote frequently about educational programs. He examined the "intellectual tools" available in Haiti and challenged the elite to promote progress among the masses because of their advantage of position.

He ultimately came to embrace Haiti's slavery history as the true source of the Haitian identity and culture. He admired the culture and religion developed among the slaves as their base for rebelling against the Europeans and building a Haitian nation.

Collective bovarysme was also used to describe predominantly black Dominicans that denied their African roots in favor of their Spanish ancestry.[4] During the Dominican Independence War, many pro-independence Dominicans looking to gain support from Europe and the United States did not see themselves as black. They viewed the conflict as a war between whites and blacks, or between the "civilized" and "barbaric".[4]

Notable Works

- La Vocation de l'elite (1919)

- Ainsi parla l'oncle (1928) Translated: So Spoke the Uncle (1983)

- La République d'Haïti et la République Dominicaine (1953)

- De Saint-Domingue à Haïti (1957)

Further reading

- Jean Price-Mars and Haiti, by Jacques C. Antoine. Three Continents Press. 1981

- San Miguel, Pedro L. (2005). The Imagined Island: History, Identity, and Utopia in Hispaniola. United States: The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 67–97. ISBN 0-8078-5627-4.

- Schutt-Ainé, Patricia (1994). Haiti: A Basic Reference Book. Miami, Florida: Librairie Au Service de la Culture. p. 105. ISBN 0-9638599-0-0.

- "The Religious Imagination and Ideas of Jean Price-Mars" (Part 1), by Celucien Joseph, Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Religion Volume 2, Issue 14 (December 2011):1-31

- Joseph, Celucien L. From Toussaint to Price-Mars: Rhetoric, Race, and Religion in Haitian Thought (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013)

- Robinson, Christine 'Jean Price-Mars: Haitian anthropologist and man of ideas' in Encyclopedia of Latin American Literature, Verity Smith ed. (Fitzroy Dearborn, London: 1997) pp.675-676

References

- Île-en-île Jean Price-Mars

- Encyclopedia of U.S. Military Interventions in Latin America (Volume I). Santa Barbara, California. Alan McPherson, editor. (2013)

- The Imagined Island: History, Identity, and Utopia in Hispaniola. Pedro L. San Miguel (2005) University of North Carolina Press.

- Enciclopedia de Puerto Rico. Un proyecto de la Fundación Puertorriqueña de las Humanidades y el National Endowment for the Humanities.