Japonisme

Japonisme[lower-alpha 1] is a French term that refers to the popularity and influence of Japanese art and design in western Europe in the nineteenth century following the forced reopening of trade of Japan in 1858.[1][2]

Japonisme was first described by French art critic and collector Philippe Burty in 1872.[3]

Art forms

Ukiyo-e

From the 1860s, ukiyo-e, Japanese woodblock prints, became a source of inspiration for many Western artists.[4] These prints were created for the commercial market in Japan.[4] Although a percentage of prints were brought to the West through Dutch trade merchants, it was not until the 1860s that ukiyo-e prints gained popularity in Europe.[4] Western artists were intrigued by the original use of color and composition. Ukiyo-e prints featured dramatic foreshortening and asymmetrical compositions.[5]

Decorative arts

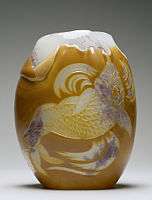

Gregory Irvine argues that Japanese decorative arts, including ceramics, enamels, metalwork, and lacquerware, were as influential in the West as the graphic arts.[6] During the Meiji era, Japanese pottery was very successfully exported around the world.[7] From a long history of making weapons for samurai, Japanese metalworkers had achieved a very expressive range of colours by combining and finishing metal alloys.[8] Japanese cloissoné enamel reached its "golden age" from 1890 to 1910,[9] producing items more advanced than ever before.[10] Lacquer from Japanese workshops was recognised as technically superior to what could be produced anywhere else in the world.[11] These items were widely visible in nineteenth-century Europe: a succession of world's fairs displayed Japanese decorative art to millions[12][13] and it was picked up by galleries and fashionable stores.[6] Writings by critics, collectors and artists expressed considerable excitement about this "new" art.[6] Collectors including Siegfried Bing[14] and Christopher Dresser[15] displayed and wrote about these works. Thus Japanese styles and themes reappeared in the work of Western artists and craftsmen.[6]

History

_(part_of_a_set)_MET_DP105715.jpg)

Seclusion (1639–1858)

During the Edo period (1639–1858), Japan was in a period of seclusion and only one international port remained active.[16] Tokugawa Iemitsu ordered that an island, Dejima, be built off the shores of Nagasaki from which Japan could receive imports.[16] The Dutch were the only country able to engage in trade with the Japanese, however, this small amount of contact still allowed for Japanese art to influence the West.[17] Every year the Dutch arrived in Japan with fleets of ships filled with Western goods for trade.[18] In the cargoes arrived many Dutch treatises on painting and a number of Dutch prints.[18] Shiba Kōkan (1747–1818) was one of the notable Japanese artists that studied the Dutch imports.[18] Kōkan created one of the first etchings in Japan which was a technique he had learned from one of the imported treatises.[18] Kōkan would combine the technique of linear perspective, which he learned from a treatise, with his own ukiyo-e styled paintings.

_(cropped).jpeg)

Seclusion era porcelain

Through the seclusion era, Japanese goods remained a sought after luxury by European monarchs.[19] Japanese porcelain manufacturing began in the seventeenth century after Korean potters settled in Kyusyu area. They unearthed kaolin clay near Nagasaki and began to make high quality pottery.[19] Japanese manufacturers were aware of the popularity of porcelain in Europe, therefore, some products were specifically produced for the Dutch trade.[19] Porcelain and lacquerware became the main exports from Japan to Europe.[20] Porcelain was used to decorate the homes of monarchs in the Baroque and Rococo style.[20] A popular way to display porcelain in a home was to create a porcelain room. Shelves would be placed throughout the room to display the exotic decorations.[20]

Nineteenth-century re-opening

During the Kaei era (1848–1854), after more than 200 years of seclusion, foreign merchant ships of various nationalities began to visit Japan. Following the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Japan ended a long period of national isolation and became open to imports from the West, including photography and printing techniques. With this new opening in trade, Japanese art and artifacts began to appear in small curiosity shops in Paris and London.[21] Japonisme began as a craze for collecting Japanese art, particularly ukiyo-e. Some of the first samples of ukiyo-e were to be seen in Paris.[22] In about 1856 the French artist Félix Bracquemond first came across a copy of the sketch book Hokusai Manga at the workshop of his printer, Auguste Delâtre.[23] The sketchbook had arrived in Delâtre's workshop shortly after Japanese ports had opened to the global economy in 1854; therefore, Japanese artwork had not yet gained popularity in the West.[24] In the years following this discovery, there was an increase of interest in Japanese prints. They were sold in curiosity shops, tea warehouses, and larger shops.[23] Shops such as La Porte Chinoise specialized in the sale of Japanese and Chinese imports.[23] La Porte Chinoise, in particular, attracted artists James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas who drew inspiration from the prints.[25] European artists at this time were seeking an alternative style to the strict academic methodologies.[26] Gatherings organized by shops like La Porte Chinoise facilitated the spread of information regarding Japanese art and techniques.[26]

Artists and Japonisme

Ukiyo-e prints were one of the main Japanese influences on Western art. Western artists were inspired by different uses of compositional space, flattening of planes, and abstract approaches to color. An emphasis on diagonals, asymmetry, and negative space can be seen in the Western artists who were influenced by this style.[27]

Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh began his deep interest in Japanese prints when he discovered illustrations by Félix Régamey featured in The Illustrated London News and Le Monde Illustré.[28] Régamey created woodblock prints, followed Japanese techniques, and often depicted scenes of Japanese life.[28] Van Gogh used Régamey as a reliable source for the artistic practices and everyday life scenes of the Japanese. Beginning in 1885, van Gogh switched from collecting magazine illustrations, such as Régamey, to collection ukiyo-e prints that could be bought in small Parisian shops.[28] Van Gogh shared these prints with his contemporaries and organized a Japanese print exhibition in Paris in 1887.[28]

Van Gogh's Portrait of Père Tanguy (1887) is a portrait of his color merchant, Julien Tanguy. Van Gogh created two versions of this portrait, which both feature a backdrop of Japanese prints.[29] Many of the prints behind Tanguy can be identified, with artists such as Hiroshige and Kunisada featured. Van Gogh filled the portrait with vibrant colors. He believed that buyers were no longer interested in grey-toned Dutch paintings, rather paintings with many colors were seen as modern and were sought after.[30] He was inspired by Japanese woodblock prints and their colorful palettes. Van Gogh included into his own works the vibrancy of color in the foreground and the background of paintings that he observed in Japanese woodblock prints and made use of light to clarify.[30]

Edgar Degas

In the 1860s, Edgar Degas began to collect Japanese prints from La Porte Chinoise and other small print shops in Paris.[31] Degas’ contemporaries had begun to collect prints as well, which gave him a large collection for inspiration.[31] Among the prints shown to Degas was a copy of Hokusai's Random Sketches, which had been purchased by Bracquemond after seeing it in Delâtre's workshop.[26] The estimated date of Degas’ adoption of japonismes into his prints is 1875.[31] The Japanese print style can be seen in Degas’ choice to divide individual scenes by placing barriers vertically, diagonally and horizontally.[31]

Similar to many Japanese artists, Degas’ prints focus on women and their daily routines.[32] The atypical positioning of his female figures and the dedication to reality in Degas’ prints aligned him with Japanese printmakers such as Hokusai, Utamaro, and Sukenobu.[32] In Degas' print Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: The Etruscan Gallery (1879–1880), the commonalities between Japanese prints and Degas' work can be found in the two figures: one that stands and one that sits.[33] The composition of the figures was familiar in Japanese prints. Degas also continues the use of lines to create depth and separate space within the scene.[33] Degas' most clear appropriation is of the woman leaning on a closed umbrella which is borrowed directly from Hokusai's Random Sketches.[34]

James McNeill Whistler

Japanese art was exhibited in Britain beginning in the early 1850s.[35] These exhibitions featured a variation of Japanese objects, including maps, letters, textiles and objects from everyday life.[36] These exhibitions served as a source of national pride for Britain and served to create a separate Japanese identity apart from the generalized "Orient" cultural identity.[37]

James Abbott McNeill Whistler was an American artist who worked primarily in Britain. During the late 19th century, Whistler began to reject the Realist style of painting that his contemporaries favored. Instead, Whistler found simplicity and technicality in the Japanese aesthetic.[38] Rather than copying specific Japanese artists and artworks, Whistler was influenced by general Japanese methods of articulation and composition, which he integrated into his works.[38]

Artists influenced by Japanese art and culture

Japanese gardens

The aesthetic of Japanese gardens was introduced to the English-speaking world by Josiah Conder's Landscape Gardening in Japan (Kelly & Walsh, 1893). It sparked the first Japanese gardens in the West. A second edition was required in 1912.[39] Conder's principles have sometimes proved hard to follow:

Robbed of its local garb and mannerisms, the Japanese method reveals aesthetic principles applicable to the gardens of any country, teaching, as it does, how to convert into a poem or picture a composition, which, with all its variety of detail, otherwise lacks unity and intent.[40]

Tassa (Saburo) Eida created several influential gardens, two for the Japan–British Exhibition in London in 1910, and one built over four years for William Walker, 1st Baron Wavertree;[41] the latter can still be visited at the Irish National Stud.[42]

Samuel Newsom's Japanese Garden Construction (1939) offered Japanese aesthetic as a corrective in the construction of rock gardens, which owed their quite separate origins in the West to the mid-19th century desire to grow alpines in an approximation of Alpine scree. According to the Garden History Society, the Japanese landscape gardener Seyemon Kusumoto was involved in the development of around 200 gardens in the UK. In 1937, he exhibited a rock garden at the Chelsea Flower Show, and worked on the Burngreave Estate at Bognor Regis, a Japanese garden at Cottered in Hertfordshire, and courtyards at Du Cane Court in London.

The impressionist painter Claude Monet modelled parts of his garden in Giverny after Japanese elements, such as the bridge over the lily pond, which he painted numerous times. By detailing just on a few select points such as the bridge or the lilies, he was influenced by traditional Japanese visual methods found in ukiyo-e prints, of which he had a large collection.[43][44][45] He also planted a large number of native Japanese species to give it a more exotic feeling.

Museums

In the United States, the fascination with Japanese art extended to collectors and museums creating significant collections, which still exist and have influenced many generations of artist. The epicenter was Boston in no small part due to Isabella Stewart Gardner, a pioneering collector of Asian art.[46] As a consequence, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston now claims to house the finest collection of Japanese art outside Japan.[47] The Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery house the largest Asian art research library in the United States and house Japanese art together with the Japanese influenced works of Whistler.

Gallery

James McNeill Whistler, The Princess from the Land of Porcelain, 1863–1865

James McNeill Whistler, The Princess from the Land of Porcelain, 1863–1865 James Tissot, La Japonaise au bain, 1864

James Tissot, La Japonaise au bain, 1864 Félix Bracquemond, Service Rousseau, 1867

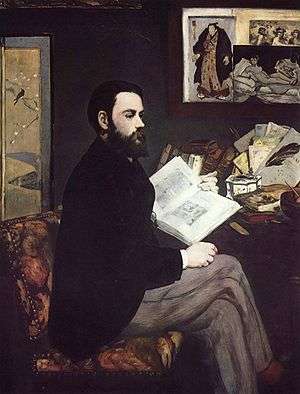

Félix Bracquemond, Service Rousseau, 1867 Édouard Manet, Portrait of Émile Zola, 1868

Édouard Manet, Portrait of Émile Zola, 1868 Gustave Léonard de Jonghe, The Japanese Fan, c. 1865

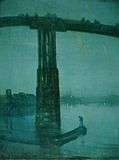

Gustave Léonard de Jonghe, The Japanese Fan, c. 1865 James McNeill Whistler, Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Old Battersea Bridge, 1872–1875

James McNeill Whistler, Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Old Battersea Bridge, 1872–1875 Claude Monet, Madame Monet en costume Japonais, 1875

Claude Monet, Madame Monet en costume Japonais, 1875 James McNeill Whistler, The Peacock Room, 1876–1877

James McNeill Whistler, The Peacock Room, 1876–1877 Vincent van Gogh, La courtisane (after Keisai Eisen), 1887

Vincent van Gogh, La courtisane (after Keisai Eisen), 1887 Vincent van Gogh, The Blooming Plum Tree (after Hiroshige's Plum Park in Kameido), 1887

Vincent van Gogh, The Blooming Plum Tree (after Hiroshige's Plum Park in Kameido), 1887_1892.jpg) Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec lithograph poster of 1892

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec lithograph poster of 1892.jpg)

Odilon Redon, The Buddha, 1906

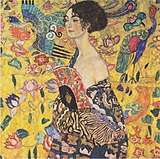

Odilon Redon, The Buddha, 1906 Gustav Klimt, Lady with fan, 1917/18

Gustav Klimt, Lady with fan, 1917/18

Fall-front desk, an example of Anglo-Japanese furniture; 1875–1880, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Fall-front desk, an example of Anglo-Japanese furniture; 1875–1880, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

See also

- Anglo-Japanese style

- Arabist – "Arab" style

- Chinoiserie – similar Chinese influence on Western art and design

- Occidentalism – for Eastern views of the West

- Orientalism – Western romanticized depictions of Asian (more often Near Eastern) subject matter

- Woodblock printing in Japan

- Woodcut

Notes

- From the French Japonisme

References

- References

- "Japonism". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- "Commodore Perry and Japan (1853–1854) | Asia for Educators | Columbia University". afe.easia.columbia.edu. Retrieved 2020-02-02.

- Ono 2003, p. 1

- Bickford, Lawrence (1993). "Ukiyo-e Print History". Impressions (17): 1. JSTOR 42597774.

- Ono 2003, p. 45

- Irvine 2013, p. 11.

- Earle 1999, p. 330.

- Earle 1999, p. 66.

- Irvine 2013, p. 177.

- Earle 1999, p. 252.

- Earle 1999, p. 187.

- Irvine 2013, pp. 26–38.

- Earle 1999, p. 10.

- Irvine 2013, p. 36.

- Irvine 2013, p. 38.

- Lambourne 2005, p. 13

- Gianfreda, Sandra. "Introduction." In Monet, Gauguin, Van Gogh… Japanese Inspirations, edited by Museum Folkwang, Essen, 14. Gottingen: Folkwang/Steidl, 2014.

- Lambourne 2005, p. 14

- Lambourne 2005, p. 16

- Chisaburo, Yamada. "Exchange of Influences in the Fine Arts between Japan and Europe." Japonisme in Art: An International Symposium (1980): 14.

- Cate et al. 1975, p. 1

- Yvonne Thirion, "Le japonisme en France dans la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle à la faveur de la diffusion de l'estampe japonaise", 1961, Cahiers de l'Association internationale des études francaises, Volume 13, Numéro 13, pp. 117–130. DOI 10.3406/caief.1961.2193

- Cate et al. 1975, p. 3

- Breuer 2010, p. 67

- Cate et al. 1975, p. 4

- Breuer 2010, p. 68

- Breuer 2010, p. 41

- Thomson 2014, p. 70

- Thomson 2014, p. 71

- Thomson 2014, p. 72

- Cate et al. 1975, p. 12

- Cate et al. 1975, p. 13

- Breuer 2010, p. 75

- Breuer 2010, p. 78

- Ono 2003, p. 5

- Ono 2003, p. 8

- Ono 2003, p. 6

- Ono 2003, p. 42

- Slawson 1987, p. 15 and note2.

- Conder quoted in Slawson 1987, p. 15.

- Britain and Japan: Biographical Portraits. Global Oriental. 2010. p. 503.

- "Japanese Garden". Irish National Stud. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- "Giverny | Collection of japanese prints of Claude Monet". Giverny hébergement, hôtels, chambres d'hôtes, gîtes, restaurants, informations, artistes... 2013-11-30. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- Genevieve Aitken, Marianne Delafond. La collection d'estampes Japonaises de Claude Monet. La Bibliotheque des Arts. 2003. ISBN 978-2884531092

- "The japanese prints". The Claude Monet Foundation. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- 1957–, Chong, Alan (2009). Journeys east: Isabella Stewart Gardner and Asia. Murai, Noriko., Guth, Christine., Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. [Boston]: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. ISBN 978-1934772751. OCLC 294884928.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Art of Asia". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. 2010-10-15. Retrieved 2017-09-27.

- "George Hendrik Breitner – Girl in White Kimono". Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Archived from the original on 9 September 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Sources

- Breuer, Karin (2010). Japanesque: The Japanese Print in the Era of Impressionism. New York: Prestel Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cate, Phillip Dennis; Eidelberg, Martin; Johnston, William R.; Needham, Gerald; Weisberg, Gabriel P. (1975). Japonisme: Japanese Influence on French Art 1854–1910. Kent State University Press.

- Earle, Joe (1999). Splendors of Meiji: treasures of imperial Japan: masterpieces from the Khalili Collection. St. Petersburg, Fla.: Broughton International Inc. ISBN 1874780137. OCLC 42476594.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Irvine, Gregory, ed. (2013). Japonisme and the rise of the modern art movement: the arts of the Meiji period: the Khalili collection. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-23913-1. OCLC 853452453.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lambourne, Lionel (2005). Japonisme: cultural crossings between Japan and the West. New York: Phaidon.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ono, Ayako (2003). Japonisme in Britain: Whistler, Menpes, Henry, Hornel and nineteenth-century Japan. New York: Routledge Curzon.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Slawson, David A. (1987). Secret Teachings in the Art of Japanese Gardens. New York/Tokyo: Kodansha.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thomson, Belinda (2014). "Japonisme in the Works of Van Gogh, Gauguin, Bernard and Anquetin". In Museum Folkwang (ed.). Monet, Gauguin, Van Gogh… Japanese Inspirations. Folkwang/Steidl.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Rümelin, Christian, and Ellis Tinios. The Japanese and French Print in the Era of Impressionism (2013)

- Scheyer, Ernst. “Far Eastern Art and French Impressionism,” The Art Quarterly 6#2 (Spring, 1943): 116–143.

- Weisberg, Gabriel P. "Reflecting on Japonisme: The State of the Discipline in the Visual Arts." Journal of Japonisme 1.1 (2016): 3–16. online

- Weisberg, Gabriel P. and Yvonne M.L. Weisberg. Japonisme, An Annotated Bibliography (1990).

- Wichmann, Siegfried. Japonisme. The Japanese Influence on Western Art in the 19th and 20th Centuries (Harmony Books, 1981).

- Widar, Halen. Christopher Dresser. (1990).

- thesis: Edo print art and its Western interpretations (PDF)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Japonism. |

- "Japonisme" from the Metropolitan Museum of Art Timeline of Art History

- "Orientalism, Absence, and Quick~Firing Guns:The Emergence of Japan as a Western Text"

- "Japonisme: Exploration and Celebration"

- Marc Maison's Gallery specialized in japonisme

- The Private Collection of Edgar Degas, fully digitized text from The Metropolitan Museum of Art libraries; contains essay Degas, Japanese Prints, and Japonisme (pgs 247–260)