James V. Forrestal Building

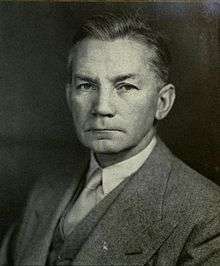

The James V. Forrestal Building is a low-rise Brutalist office building located in Washington, D.C., in the United States. Originally known as Federal Office Building 5, and nicknamed the Little Pentagon, the Forrestal Building was constructed between 1965 and 1969 to accommodate United States armed forces personnel. It is named after James Forrestal, the first United States Secretary of Defense. It became the headquarters of the United States Department of Energy after that agency's creation in 1977.

| James V. Forrestal Building | |

|---|---|

James V. Forrestal Building in 2006. | |

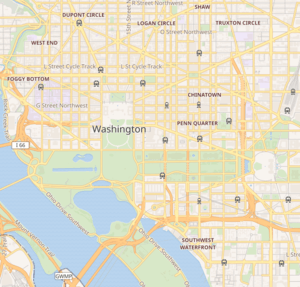

Location within Central Washington, D.C. | |

| Alternative names | United States Department of Energy Headquarters |

| General information | |

| Type | Government office building |

| Architectural style | Brutalist |

| Address | 1000 Independence Avenue SW, Washington, D.C. |

| Coordinates | 38.887024°N 77.025987°W |

| Construction started | September 1965 |

| Completed | November 18, 1969 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architecture firm | Curtis & Davis; Fordyce and Hamby Associates; Frank Grad & Sons |

| Website | |

| Energy.gov | |

The 1,688,484-square-foot (156,865.3 m2) Forrestal Building is located at 1000 Independence Avenue SW. It consists of three structures: an East Building with eight floors above ground, the North Building with four floors above ground, and a West Building with two floors above ground. All three structures are connected by two floors of underground office space. In order to provide access to L'Enfant Plaza, the North Building is raised up on 35-foot-high (11 m) pilotis (or columns).

Conflict over the site

The area of Southwestern Washington, D.C., where the Forrestal Building is located was originally laid out in a grid pattern as specified by the L'Enfant Plan of 1791.[1] By the early 1900s, Victorian-style rowhouses lined the south side of B Street SW (later renamed Independence Avenue SW). In 1901, the Senate Park Commission proposed a plan for the development of the monumental core and parks of the District of Columbia. The plan called for federal office buildings and museums to line the north and south sides of the National Mall. But little development of the area occurred.

Conflict with the Smithsonian

The first building proposed for the site was the Smithsonian Institution's National Air Museum. The museum, which was chartered in 1946, needed a new structure to house its rapidly expanding collection of aircraft and missiles. The National Air Museum Advisory Board, established to advise the Smithsonian about the operation of the new museum, recommended in 1953 that the new museum be located on Independence Avenue between 9th and 12th Streets SW. In June 1954, the Smithsonian sought the approval of the National Capital Planning Commission.[2]

However, a major redevelopment of much of Southwestern D.C. conflicted with the Smithsonian proposal. At the time, Southwest D.C. was mostly a slum which suffered from high concentrations of old and poorly maintained buildings, overcrowding, and threats to public health (such as lack of running indoor water, sewage systems, electricity, central heating, and indoor toilets).[3] In 1946, the United States Congress passed the District of Columbia Redevelopment Act, which established the District of Columbia Redevelopment Land Agency (RLA) and provided legal authority to clear land as well as funds to spur redevelopment in the capital.[4] Congress also gave the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) the authority to designate which land would be redeveloped, and how.[5] Wholesale razing of hundreds of acres of land in Southwest D.C. was contemplated. As early as 1952, there were already several proposals to transform 10th Street SW. These included constructing an esplanade above 10th Street SW,[6] creating a traffic circle at the intersection of 10th Street and Independence Avenue SW,[7] and using 10th Street as a major thoroughfare for traffic coming off the 14th Street Bridge.[8] Some of these proposals had won the tentative support of the NCPC.[9] In February 1954, New York City developer William Zeckendorf proposed the creation of "L'Enfant Plaza" — a major development consisting of five office buildings, a cultural center, and a shopping mall. Zeckendorf's plan would replace 10th Street SW with a 400-foot (120 m) wide, grass-lined pedestrian mall.[10] The NCPC subsequently approved nearly all of Zeckendorf's proposal in April 1955, including the 10th Street mall.[11]

Conflict between the Smithsonian and Zeckendorf plans came to a head in late 1955. The Smithsonian had approached Zeckendorf in February 1954 and proposed that their airplane museum become the "cultural center" envisioned by the redevelopment plan.[12] But nothing came of this proposal. In September 1954, the NCPC came close to reversing itself and approving the Smithsonian plan. But John Remon, chairman of the RLA, strenuously objected.[12] In February 1955, the NCPC tentatively approved the area on the south side of Independence Avenue SW between 9th and 12th Streets for the Air Museum. But it reversed itself in April, and said 10th Street SW would go through all the way to Independence Avenue.[13] The approval of first one plan and then another created great controversy. The NCPC formally suspended its decision-making process in late November[14] because of the Smithsonian's desire to build along Independence Avenue.[15] At issue was a memorandum of understanding (MOU) signed by Zeckendorf and the RLA in 1954. The MOU stated that 10th Street would be used as an esplanade[16] — a use which would be denied if 10th Street were blocked off at its northern end by a large museum building.

Resolution of the conflict in favor of GSA

The impasse was broken by a third party. During World War I, an office building named the Munitions Building was built on the north side of the National Mall between 19th and 21st Streets NW. Designed to be temporary, it had never been torn down. A second, nearly identical temporary building, the Main Navy Building, was constructed east of it in 1941. Attempts to have the "tempos" demolished were made over the years, but these efforts had little effect. In March 1954, however, legislation was introduced in Congress to fund the demolition.[17] But there was no place to house the displaced defense workers. Attention turned to the General Services Administration (GSA), the federal agency which owns most U.S. government buildings. GSA worried that spending federal funds for construction immediately would worsen inflation (which was running high at the time). The agency said it preferred to purchase land and pay for the construction of new federal buildings to house these workers through the use of federal "lease-purchase" legislation.[18] This World War II-era statute allowed the GSA to lease land and permit a private developer to construct a building. GSA would provide financial guarantees to enable the developer to obtain financing for the building's construction, as well as agree to a long-term lease of the structure. Lease-purchase gave GSA the option of buying the land and building at the end of 20 or 30 years, with its lease payments being put toward the cost of the structure. Although the lease-purchase legislation did not specifically include the District, GSA thought it could be interpreted that way.

GSA was not completely convinced of the need for new federal construction at first. However, in November 1954 the agency released a new study which showed that the cost of maintaining the "tempos" compared unfavorably with the cost of new construction.[19] Five months later, GSA proposed that several new federal office buildings be constructed in Washington, D.C., including one or more buildings along 10th Street SW.[18] In June 1955, GSA announced it would definitely build a six-story, $20.2 million federal office building somewhere within the Southwest D.C. redevelopment area.[20]

GSA's decision did not necessarily mean that a federal building would be built at the north end of 10th Street NW. In fact, the dispute between the Smithsonian and Zeckendorf over the Air Museum had still not been resolved by June 1955.[13] But the General Services Administration had more political influence in Congress than either of them.

Obtaining funding

GSA moved ahead with its plans. In 1955, Congress authorized a GSA proposal to construct nine new federal buildings, including one in Southwest D.C.[21] Congress also enacted a lease-purchase statute which applied only to the District of Columbia. The act required congressional approval of the building requirements and architectural design, and an open bidding process.[22] In July 1956, the House of Representatives appropriated $40.9 million for a federal building on Independence Avenue SW between 6th and 9th Streets, and $25.2 million for three small office buildings to border the 10th Street SW esplanade. All the buildings would be financed under new lease-purchase legislation.[23]

But pressure was also building in Congress to end the lease-purchase program. In large measure, this was because Congress wanted more control over the placement and design of federal buildings. The RLA agreed in January 1957 to expedite the construction of any federal buildings in the redevelopment area.[24] But because of the uncertainty about the lease-purchase legislation, GSA deferred construction of any building in February 1957.[25] In March, the House of Representatives voted to end the lease-purchase program, and provided authorization for GSA to purchase outright any land or buildings it needed. But the House also put an immediate moratorium on new federal construction in the city.[26] Among the structures suddenly in limbo were:[26]

- Federal Office Building No. 6 at 400 Maryland Avenue SW. (It eventually opened in 1961 and was originally the headquarters of the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. In 1979, it became the headquarters of the United States Department of Education.)[24]

- Federal Office Building No. 8 at 200 C Street SW. (It eventually opened in 1965, and originally housed laboratories of the United States Food and Drug Administration. The agency moved to new, larger headquarters in Maryland in 2001, and in 2010 a $73 million project began to gut the structure and radically renovate the interior and exterior for occupancy by members of Congress and some smaller units of the United States Department of Health and Human Services.)[27][28]

- Federal Office Building Number 9 at 1900 E Street NW. (It began construction in 1962. It is now known as the Theodore Roosevelt Federal Building and is home to the United States Office of Personnel Management).[29]

- Federal Office Building Number 10 at 7th Street SW and Independence Avenue SW. (It was constructed in 1963 as two separate structures, rather than a single structure that would block 7th Street SW. 800 Independence Avenue SW houses the Federal Aviation Administration. 676 Independence Avenue SW originally housed two units of NASA, but today also contains offices of the Federal Aviation Administration.)[30]

Members of Congress justified the moratorium on the grounds that the economy in the District of Columbia did not need any economic stimulus.[26] Despite these problems, GSA in 1957 selected the 10th Street and Independence Avenue SW site for the construction of Federal Office Building 5. Although other sites were considered, the kind and number of defense employees to be housed in the building, these workers' impact on traffic flow in and around the city, and other factors led GSA to choose this site.[31]

GSA intended for the United States Navy to occupy the new building, but this caused issues as well. The Navy (like all non-Cabinet agencies) was barred by the President from leasing or building a headquarters closer than 25 miles (40 km) from the center of Washington, D.C.[32] Nevertheless, certain civic leaders wanted President Dwight Eisenhower to allow the Navy to remain in the city limits. These individuals advocated the construction of a major new federal office complex, to be known as Federal City Center, in an area bounded by Pennsylvania Avenue NW, E Street NW, 8th Street NW, and 11th Street NW (an area that now encompasses 1001 Pennsylvania Avenue and the J. Edgar Hoover Building). Although GSA did not necessarily agree that the Navy should occupy Federal City Center, it did say in August 1959 that most Navy offices be combined into a single, unspecified headquarters — which it called "the little Pentagon".[33] For its part, the Navy dutifully began seeking office space outside the 25-mile (40 km) limit. Its preference was an office complex near the Capital Beltway in Fairfax County, Virginia.[34]

In 1958 and 1959, most of the obstacles to the construction of Federal Office Building 5 were removed. Congress enacted legislation in 1958 authorizing the construction of the museum on the north side of Independence Avenue between 4th and 7th Streets SW.[35] In 1959, when Congress passed legislation authorizing the construction of GSA's "Little Pentagon" project, removing the distance limitation. Funds for the construction were appropriated in 1960.[24] The exact location of the structure was still unclear, but GSA wanted it built on Independence Avenue. The construction of such a large complex was not considered to be a problem. Congress and GSA believed that a large building helped to create a "dramatic northern boundary" for the redevelopment area.[36] There was still some doubt as to which tenants would occupy the "Little Pentagon". There was some indication that Federal Office Building 10 would house the "Little Pentagon". But in January 1961, GSA allocated Federal Office Building 10 to the Federal Aviation Administration and said it would build the "Little Pentagon" elsewhere in Southwest.[37]

In January 1961, GSA asked Congress to authorize construction of the "Little Pentagon" at 10th and Independence.[38] The United States Department of Defense intended to put 7,000 Air Force and Army personnel in the structure, and GSA told Congress that a call for architectural bids would be issued in July.[39] GSA head John L. Moore said the agency was open to a Modernist architectural design, and that the building should be ready for occupancy within five years.[40] In June, GSA said the "Little Pentagon" would be built on just 9.6 acres (39,000 m2) of land. The total budget was $42 million, of which $3.8 million would be spent on land and $2 million on fallout shelters.[41] The number of workers in the building, pegged at 7,000 in May, had now risen to 7,500.[42] A major change in the structure's purpose came in July 1961 when GSA said that the U.S. Navy would instead occupy the building, which now was set to have 1 million square feet (93,000 m2) of office space.[43]

Design issues

When the federal government issued its call for proposals, it specified a building with 2 million square feet (190,000 m2) of office space, dining facilities for 2,500 people, and an underground parking garage for 1,800 automobiles.[44] (Architect David Dibner, who was the project partner on the building, says the prospectus called for two wings of 890,100 square feet (82,690 m2).)[45] The architectural firms of Curtis & Davis, Fordyce and Hamby Associates, and Frank Grad & Sons formed a joint venture which won the design competition for the $38 million structure on October 3, 1961.[45][46][47] Architect David R. Dibner led the joint venture's design team. (In 1972, he wrote a book about his experiences, Joint Ventures for Architects and Engineers.)[48]

Conflict over a span across 10th Street SW

Design issues now held up the project.

The first involved the physical design of the building. Numerous plans in the last several years had called for two buildings, one on either side of 10th Street SW. Two or more levels of office space would connect them underground.[49] But the Navy strongly disliked this plan, and demanded that the structure arch over the street.[50] The purpose of the span was to improve employee circulation.[27] The architectural team also favored this plan. Its first proposal was a block-long, 10-story building pierced by a 35-foot (11 m) high space at ground level to permit 10th Street SW to pass through it. Two low, symmetrical wings extended toward the Landover Subdivision railroad tracks in the south. GSA immediately approved the architects' proposal.[45]

Neither the NCPC nor the United States Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) opposed this plan.[51] The CFA reviews and provides advice on "matters of design and aesthetics" involving federal projects and planning in Washington, D.C. The first design was presented to the CFA on December 6, 1961.[52] For the CFA, the issue was not the span over 10th Street but rather whether the façade was in "harmony with the character of Washington as the Nation's Capital."[53] Indeed, the CFA applauded the design, believing it would help frame the Mall and preserve the line of sight along Independence Avenue (which it considered more important).[53] The CFA also felt the span would help create a gateway to L'Enfant Plaza. It claimed there would be a "dramatic effect of passing through the arch and suddenly seeing a new vista open up."[54] The proposed design was presented to the NCPC on December 6, 1961.[45] The agency approved the plan on March 1, 1962, but suggested that the design team coordinate with the RLA.[55] Perhaps fearing public outcry, both the NCPC and CFA pushed the project through their respective approval processes with little public awareness.[54]

According to Dibner, the RLA also approved the design. But the land agency also said that the architects should consult with William Zeckendorf and his architects so that the federal building's design could be coordinated with the design of L'Enfant Plaza. According to Dibner, the first meeting between the two sides was to have occurred on March 20, 1962.[56]

For his part, Zeckendorf already strongly opposed the span design. He argued that the 780-foot (240 m) long span would act like a wall, blocking off L'Enfant Plaza as effectively as the slums had. He also argued it violated the concept of an esplanade, as guaranteed in the MOU of 1954. GSA countered that by placing the building 36 feet (11 m) in the air, the vista to the National Mall was preserved. It also said that Zeckendorf's plan, which placed high-rise office buildings along 10th Street, would create a "canyon effect" that would destroy the vistas provided by the esplanade and that the span was critical to maintaining an effective flow of employees within the building.[57]

Although the two sides met again several times, no agreement could be reached. The GSA, NCPC, and RLA, however, agreed that the joint venture's plan for the building should proceed.[56]

The real impediment to building the structure was that federal government did not own the air rights over 10th Street SW, which was a street under the jurisdiction of the District of Columbia. In early 1962, GSA submitted legislation to Congress giving the agency these air rights.[51] The House passed this legislation in July,[56] and Senate approved it in August 1962.[57]

Conflict over the building's aesthetics

The second design obstacle involved the look of the building. Arthur Q. Davis, of Davis & Curtis, said that the design team's goal was to avoid the typical blocky, monumental mass that typified too many office buildings. The architects wanted to introduce a "new vocabulary" to D.C. architecture, one which emphasized a sense of floating, gracefulness, and rectilinear elements.[58] According to Nathaniel Curtis, Jr., Davis's business partner, "A controversy existed between those who wanted to maintain the granite and marble of the Federal City and the new thinkers who favored exposed aggregate concrete, steel, and glass."[59] In April 1963,[52] the joint venture led by Curtis & Davis produced a low structure with glass panels held in place by aluminum frames. Two symmetrical wings extended down either side of 10th Street SW. CFA, however, felt that the Modernist structure did not fit with the Neoclassical architecture of the capital.[60] The CFA, which had explicit statutory authority over the aesthetics of the building, prodded the architectural joint venture to design a smaller building and to use traditional masonry. The commission argued that "uniqueness of individual design" must come second to retaining a unified look for buildings along the National Mall.[53]

After meeting with high-level GSA officials, the joint venture team produced a second design. Presented to the CFA on September 18, 1963, the new design featured a wall consisting of thin, vertical concrete ribs in front of a glass wall. A concrete band covered the roofline and the bottom of the structure.[52] By this time, however, six of the seven CFA members who had reviewed the April 1963 proposal were gone—their appointments to the commission having expired. The "new" CFA rejected the concrete rib treatment, again pushing for a masonry look compatible with nearby buildings. The design team argued that nearby structures were clad in buff limestone, red sandstone, white marble, and pink concrete and that there was no way to adopt a compatible façade.[52]

Nevertheless, a third design was submitted by the design team on October 15, 1963. In the meantime, the final member of the CFA had been appointed, leading to a change of views once more. This time, the CFA rejected the entire project, including the space beneath the structure for 10th Street SW. The CFA suggested three possible designs it would accept: 1) Elimination of 10th Street SW and the creation of a single large structure; 2) Two separate buildings with no connection over 10th Street SW; and 3) Two separate buildings with only one or two glass pedestrian skyways connecting them.[52]

The debate between the CFA and joint venture had now lasted several months, and the Department of Defense (DOD) became frustrated because its structure still had not been built. With the additional pressure from DOD, the architects agreed to redesign the façade yet again. A new design consisting of three buildings of different massings was presented to the CFA on November 20, 1963. But the CFA said that it had changed its mind again, and would accept only a single large structure blocking off 10th Street SW.[52] Conflict now emerged between the CFA and NCPC. On November 5, 1963, the NCPC reiterated its approval for a three-building solution with a span over 10th Street SW.[52] NCPC approval was required, but the CFA was merely an advisory body. GSA brokered a meeting of the two bodies to resolve their differences.

The CFA and NCPC met in the first joint session in their respective histories on January 9, 1964.[61] A final design team effort[61] was presented to the CFA and NCPC during the January 1964 meeting.[62] The treatment used rectilinear, precast concrete windows with large glass panels as the north façade of the North Building, and the east, west, and south façades of the East and West buildings. The design team felt this preserved their goal of having large areas of glass face Independence Avenue.[58] The North Building was also smaller than originally proposed. Now just four stories high, it was pierced in the middle near both ends by columns designed to contain the mechanical equipment — making the structure look much more like a bridge or arch.[60] Also gone were the identical high-rise structures extending down 10th Street. The East Building now was an eight-story-high, block-like mass with an interior courtyard which presented a blank, windowless façade to Independence Avenue. The West Building was now just two stories high, and contained a large auditorium as well as above-ground dining facilities.[60] The proposed structure had 1.789 million square feet (166,200 m2) of gross space and 1.263 million square feet (117,300 m2) of useable space.[62]

Although the new façade closely resembled that of the Robert C. Weaver Federal Building (then being designed by Marcel Breuer),[63] it remained highly controversial. According to Nathaniel Curtis, President John F. Kennedy himself intervened to approve the revised design. While on an airplane trip, Curtis happened to sit next to an old friend, Bob Troutman. Troutman was also Kennedy's Southeast Campaign Director. After explaining the problem the joint venture was facing, Curtis claims that Troutman spoke to Kennedy and that the President alone forced approval of the design.[59] The design team, according to Dibner, labored to complete a detailed final design and interior architectural drawings over the next few months.[61]

The approved design was made public in November 1964, and final architectural drawings were due in March 1965.[60] It was in early 1965 that President Lyndon B. Johnson issued an order christening the structure the James V. Forrestal Building, in honor of the first United States Secretary of Defense.[64] Final design details were worked out in the spring of 1965. President Johnson unveiled a model of the Forrestal Building at a joint meeting of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and the Pan American Congress of Architects. The AIA presented Johnson with a citation for the building's design.[47]

Construction

As construction neared on the Forrestal Building, there were serious concerns about the construction schedule. Zeckendorf noted that work could not begin on the esplanade until the building was finished, and the esplanade was the key to making the office buildings at L'Enfant Plaza desirable to tenants.[65] By May 1965, the cost of the structure had risen to $46 million.[66] (A different report in June put the price at $30 to $32 million.)[47] GSA asked for construction bids that same month, and Blake Construction won the contract in July.[67] Excavation work began in September, and was well under way by October.[68] In early January 1966, the Washington Post reported that the structure was due to be complete by the end of 1967.[69] But the federal government was a year behind in its construction schedule by June 1967, causing the northern end of the promenade to remain incomplete. A consultant blamed over-optimistic construction schedules and a labor shortage for the problems.[70] The building finally neared completion in April 1969.

DOD began moving into the building in April 1969,[64] although GSA admitted it would not be fully complete until November.[71]

Secretary of Defense Melvin R. Laird dedicated the Forrestal Building on November 18, 1969.[72]

Occupancy by the Department of Energy

The Department of the Navy was the original tenant of the Forrestal Building. This changed in 1977 after the creation of the Department of Energy (DOE). The new agency began operations on October 1, 1977. A large number of federal agencies, bureaus, and other organizations were brought together into a single cabinet-level department. These included large agencies such as the Federal Energy Administration (which collected data on energy resources and energy use), the Energy Research and Development Administration (which oversaw the development and testing of the nation's nuclear weapons), the Federal Power Commission (which regulated hydroelectric projects, interstate electric utilities, and the natural gas industry), and programs of various other agencies.

The preference of the Carter Administration was to bring these agencies together in a single building, if possible. GSA considered three alternatives: the Forrestal Building, the New Post Office Building (which had been vacated by the Post Office for a new building on L'Enfant Plaza), and the Casimir Pulaski Building on Massachusetts Avenue NW.[73] Occupying the Post Office Building or Pulaski Building would cost one-tenth that of occupying the Forrestal Building, because many DOE units were already located there. But neither building could house as many DOE workers as the Forrestal Building, and both were seen as only short-term solutions to DOE's space problems. On June 3, 1977, President Carter ordered GSA to make the Forrestal Building available for DOE by October 1, 1977.[74]

By this time, the Forrestal Building was occupied by the Army Corps of Engineers, the Military District of Washington, the Army Adjutant General, and several small units of the Air Force. But even if all defense workers moved out, the Forrestal Building could accommodate only about 60 percent of the Department of Energy's personnel. To house the rest, DOE retained campuses in Germantown, Maryland; at 2000 M Street NW; and at the Union Center Buildings at 825 North Capitol Street.[75]

Relocation began in October 1977. But local residents of the Southwest Waterfront neighborhood, concerned about the impact of thousands of DOD workers driving on their residential streets to get to their new work sites, sued GSA to prevent the relocation of the defense workers. On January 11, 1978, a federal district court held in S.W. Neighborhood Assembly v. Eckard, 445 F.Supp. 1195 (D.D.C.1978), that GSA had failed to conduct an environmental impact statement assessing the move.[76][77] The court also held that GSA could not relocate significant numbers of DOD personnel without providing formal notice to the citizens' association (relocation decisions which the association could contest in court). By February 1978, only 53,400 square feet (4,960 m2) of space had been vacated by DOD, and no DOE offices had moved into Forrestal.[78]

DOE personnel finally began moving into the Forrestal Building on April 28, 1978, and DOE operations officially started there on May 1.[64] By early 1980, DOE still occupied just 52 percent of the Forrestal Building.[79]

About the building

The Forrestal Building is located at 1000 Independence Avenue SW. The site is bounded by Independence Avenue SW, 9th Street SW, 11th Street SW, and the CSX railroad tracks (which run below-grade along what used to be Maryland Avenue on a southwest-northeast alignment).[80] Although the site falls within the protected historic area of the National Mall,[81] the Forrestal Building itself is not on the National Register of Historic Places.[82]

Forrestal is a single building, although it consists of three structures (often referred to as "building"): An East Building with eight floors above ground; the North Building with four floors above ground, and a West Building with two floors above ground.[83] Two floors of underground office space (including the area beneath 10th Street) connect all three structures. The exterior of the Forrestal Building is clad in pre—cast concrete units, each of which has two recessed glass windows.[84][85] The interior office space was configured by interior designers, and was one of the first large office buildings in the country to be designed by this type of professional.[86] The interior space of all three buildings is open and contains few walls. This configuration was chosen not only because it was considered a superior design, but because it was supposed to provide the greatest flexibility in office management.[85] This open space was subsequently divided into offices by installing walls, which created significant ventilation and lighting problems.[87] Although press reports at the time of its construction said the site was 9.6 acres (39,000 m2) in size, a 2005 report listed the size of the site as 15.9 acres (64,000 m2).[82] As of 2005, the building had 809 underground and 43 aboveground parking spaces.[88]

- The North Building is raised on 40 piloti (columns or piers) 35 feet (11 m) high, which creates a vast space beneath the structure.[44][84] (One source says there are only 36 pilotis.)[85] Also known as Building A/B, the North Building runs parallel to Independence Avenue between 9th and 11th Streets SW. Two building cores provide access to the structure. The "Building A" core is located west of 10th Street and serves as an emergency exit. The "Building B" core is located east of 10th Street, and serves as the main public entrance to the Forrestal Building.[84] The area below the North Building is a hardscape consisting of concrete, asphalt, and cobblestone-like rock placed in cement, punctuated by small squares of grass.[84]

- The East Building is a large, single, undifferentiated block that contains a central courtyard, and is linked to the North Building by bridges at each of the North Building's floors.[44] It flanks 10th Street SW to the east.[84] The north and south façades are blank walls, while the east and west façades consist of the same pre-cast concrete frames with windows that are used on the North Building. A balcony surrounds the second floor.

- The West Building is a low structure that flanks 10th Street to the west.[84] Due to the raised esplanade, it appears to be a single-story building on the east. Large floor-to-ceiling windows in a different type of pre-cast concrete frame form the walls of the West Building. A balcony surrounds the second floor, and a relatively flat roof overhangs the balcony.

A sunken, open-air courtyard exists between the North and East Buildings, and another between the North and West Buildings. A single-story 7,788 square feet (723.5 m2) Child Development Center was constructed adjacent to the southwest corner of the West Building in 1991.[82] In 1992, a 10-foot (3.0 m) high sculpture titled "Chthonodynamis" ("Earth Energy") was installed in front of the lobby entrance to the Forrestal Building. The sculpture, which was carved from a single block of Norwegian granite, by was created by Robert Russin and depicts the worldwide hunger for energy. "Chthonodynamis" depicts energy inside a hollow sphere, with the figure of a man attempting to contain it.[89]

The interior space of the Forrestal Building has been variously reported. The Historic American Buildings Survey reported that in 1969 the structure had 1.63 million square feet (151,000 m2) of interior space, of which 1.3 million square feet (120,000 m2) was occupiable.[85] A 1977 GSA report, however, put the occupiable space at 902,500 square feet (83,840 m2).[73] A contractor placed the total interior space at 1.143 million square feet (106,200 m2) in 1995,[90] while the GSA reported "rentable" space at 1,754,655 square feet (163,012.8 m2) in 1998.[64] The Federal Energy Management Program listed the gross interior space at 1.75 million square feet (163,000 m2) in 2001.[87] But in 2005, another DOE report said it had 1,688,484 square feet (156,865.3 m2) of total interior space[88] and just 928,878 square feet (86,295.6 m2) of occupiable space.[82]

The General Services Administration is the legal owner of the building, while the Department of Energy is the tenant.[82] Every year, GSA estimates how much it will cost to operate the building (light, heat, ventilation, air conditioning, water, sewage, etc.), and pays this amount to DOE so that DOE can operate the structure.[87] DOE purchases steam and chilled water for the HVAC system and drinking water from a nearby GSA plant.[87]

In addition to operations and maintenance, DOE is also responsible for building security, janitorial services, landscaping, lighting, parking garage operations, and road and parking lot maintenance.[91] GSA provides food services in addition to HVAC and potable water.[87][91] The two agencies are jointly responsible for renovations and upgrades (DOE providing financing, while GSA provides contracting and oversight),[91] although GSA is responsible for funding any major projects.[87]

As of 2005, approximately 3,300 federal workers and contract employees occupied the Forrestal Building.[82]

Renovations

Prior to 1993, the Forrestal Building saw no major renovation or remodeling efforts.[87] However, in 1990, DOE won a national competition sponsored by the National Endowment for the Arts. The award jury judged DOE's use of metering to improve building operations and maintenance to be of the highest quality in meeting environmental, aesthetic, innovation, technical, and other criteria.[92] Three years later, the building underwent its first major renovation when energy efficient lighting was installed.[87][93]

Major energy-efficient upgrades were made at Forrestal in 2000. A new, insulated roof was put on the structure, and solar film (designed to turn dark in strong sunlight) was applied to the windows to help keep the building cool. The Child Development Center also received energy-efficient upgrades.[94] More importantly, three solar electric photovoltaic arrays were added to the south side of the East Building and one array to the south side of the Child Development center. These arrays were a pilot project designed to study how useful solar energy could be for helping DOE meet its electrical power needs.[95]

In 2008, the Department of Energy installed a 250 kilowatt solar electric photovoltaic array on the North Building's roof.[96] Designed to generate up to 200 megawatt hours of energy annually,[97] it was one of the largest solar electric photovoltaic systems in Washington, D.C. SunPower, the array's designer, said the 891 photovoltaic units were 18.5 percent efficient, and DOE estimated they would provide about 8 percent of the Forrestal Building's power during peak usage.[97][98] The SunPower system was chosen because it did not alter the building's roof line.[96] The agency also established a new policy which required it to calculate how much energy it was saving and reinvest the funds in new energy conservation measures.[99]

In 2010, however, the Department of Energy was strongly criticized by its own Inspector general#Federal offices of inspectors general for failing to implement energy-efficient strategies at the Forrestal Building. The report said the building still used obsolete fluorescent lighting, and had never implemented its 2008 policy to track or reinvest of energy savings. Had the policy been implemented, DOE could have paid back the investment in energy conservation and renewable energy generation within two years.[99] DOE spent millions of dollars in the 1990s to develop and make commercially available "spectrally enhanced lighting" that mimicked sunlight but required 50 percent less energy to use,[100] but never adopted the lighting at its own headquarters, the report also said. In response, DOE officials said they would immediately implement plans to make the Forrestal Building "a showcase for lighting innovation." More than 600 exterior lights at the Forrestal Building would be replaced with light-emitting diodes, saving 475 megawatt-hours a year.[99]

Security upgrades

In the wake of the September 11 attacks, the Forrestal Building was identified as one of several federal buildings at high risk of terrorist attack due to its location near the U.S. Capitol and the National Mall and because of the work it does (nuclear weapons development).

In July 2003, the National Capital Planning Commission approved preliminary perimeter security enhancements for the Forrestal Building. These included the placement of bollards at pedestrian entrances, and a low wall of plinths next to the sidewalks. In 2004, DOE added jersey barriers along 10th Street and around the median running down the middle of L'Enfant Promenade (the esplanade), blocked off the taxicab stands, built temporary guard booths on the 10th Street median, and successfully petitioned the District of Columbia Department of Transportation to ban truck traffic along the northernmost portion of 10th Street. These actions were taken without the NCPC's approval.[101]

In 2005, DOE proposed additional security enhancements at the Forrestal Building. These included adding reinforced concrete shields around the pilotis (to protect them from blast damage); hardening 10th Street under the roadway with structural steel and reinforced concrete; permanent removal of the taxicab stands; the creation of a lobby around the west building core (to protect employees as they left the building); and the placement of concrete benches, concrete planters, and steel bollards along Independence Avenue and 10th Street. But DOE's most important security enhancements involved closing 10th Street and installing a blast shield. DOE proposed placing hydraulically activated bollards in the roadway at the north and south ends of the 10th Street perimeter of its site. Whenever the risk of terrorist attack was high, these bollards would rise up out of the ground and seal off the street. DOE also proposed adding a blast shield to the underside of the North Building. This shield would lower the space beneath the North Building by 9.5 feet (2.9 m) (to just 18 feet 1 inch (5.51 m)).[102]

Some of these security enhancements were accepted. The NCPC staff approved the installation of column wraps, the road hardening, and the construction of the lobby around the emergency egress building core. But the agency harshly criticized DOE for inappropriately proposing other security enhancements. The agency refused to approve the blast shield, the hydraulic bollards on 10th Street, or the emplacement of benches, planters, and bollards around the perimeter.[103] NCPC said that real security could only be achieved by dismantling the section of the North Building which extended over 10th Street SW.[104]

The Commission of Fine Arts also refused to approve the Forrestal Building blast shield, hydraulic bollards, or perimeter barriers. CFA commissioners strongly criticized the blast shield, saying it would make the building "fearful, like a bunker". CFA chairman David M. Childs essentially reversed the commission's approval of the structure in 1962, stating that the Forrestal Building did not maintain the vista along L'Enfant Promenade toward the Smithsonian Castle and the National Mall. The CFA also argued that the only way to truly secure the Forrestal Building was to remove the center section of the North Building.[105]

Critical reception

Critical reaction to the Forrestal Building has been mixed.

Initially, reviews of the design were strongly positive. Washington Post architectural critic Wolf von Eckardt called it "a work of architecture we will probably be proud of" in November 1964, and said it was "a design that promises to work – practically and aesthetically."[60] A year later, Von Eckardt compared the building's light-colored concrete (which he called sculptural) to the classic white marble of D.C.'s most beloved monuments, and said the Forrestal Building's style "may herald a new Federal architecture."[106]

But even as early as June 1965, the building's strongest supporters were beginning to have doubts. Von Eckardt called it a "pity" that it spanned 10th Street SW.[106]

Others intensely criticized the building's design from the start. I. M. Pei, who had helped design the master plan for L'Enfant Plaza, fiercely fought construction of the Forrestal Building, believing it would severely compromise the promenade's view of the National Mall.[107] Ada Louise Huxtable, architecture critic for the New York Times, wrote in 1965 that the building "failed miserably". She said it was "too big to be trivial and too competent to be offensive. But it displayed no richness of imagination and demonstrated the end result of several years of struggle by the General Services Administration, the Fine Arts Commission and the associated architects to raise a large, dull, clumsy building to an acceptable standard of design." She felt the design was "patently bad painstakingly nursed to the acceptably mediocre" by the GSA and CFA.[108] Even Von Eckardt came to see the Forrestal Building as severely flawed. In 1968, he called the structure an "esthetic disaster" (sic) and "silly"—"like an elephant tottering on the legs of a giraffe."[109] Ellen Hoffman, another architectural critic at the Washington Post, called it "hulking" after it was completed in 1969.[110]

The building's reputation has not improved over time. In 1992, a Washington Post reporter called the building "ineffably ugly".[89] The Historic American Buildings Survey concluded in 2004, "Instead of the planned vista of the Smithsonian Castle, visitors to the promenade now catch only a glimpse of that building above and below the concrete barrier located on Independence Avenue, between Ninth and Eleventh streets."[111] While the survey admitted that employee circulation was improved (as planned), the span failed to provide the intended gateway effect. Instead, it blocked off the promenade as surely as the slums and railroad tracks had.[27] In 2006, the American Institute of Architects called it the "least successful" of the Modernist buildings around L'Enfant Plaza. The association said the structure was a "bulky bar" and "grudging gateway" to the plaza and the Mall.[112] In 2010, the Washington City Paper strongly criticized the Forrestal Building for isolating the promenade from the rest of the city.[113] Architecture for Dummies author Deborah K. Dietsch said in April 2012 that it was appalling and oppressive, and that it and the J. Edgar Hoover Building topped the list of the city's ugliest buildings. Dietsch also called the span across 10th Street a "bridge to nowhere".[114]

Removing the 10th Street span

Removing the North Building's span over 10th Street SW has been the goal of several federal agencies, architectural critics, and civic leaders.

In the mid-2000s, as part of the Anacostia Waterfront Initiative, the D.C. Department of Transportation conducted a major re-evaluation of L'Enfant Plaza which concluded that removal of the span was the only way to restore the view and to remove the security risk the building caused.[85] The Commission of Fine Arts agreed in 2005. In a letter to DOE's director of security operations, CFA executive director Thomas Luebke wrote, "[T]he Commission strongly supports the removal of the center section of the building that bridges 10th Street, SW. In addition to removing the threat of a vehicle under the building, this solution would reestablish the important view from the Smithsonian Castle, down 10th Street..."[115] Luebke suggested that DOE enclose the open space beneath the North Building to add new occupiable space, reskin the entire structure, and reconfigure the mechanical system (which would have to be done at some point anyway, he said).[115]

An additional push to remove the center span came from the National Capital Planning Commission. In 2009, the NCPC released its Monumental Core Framework Plan, a comprehensive plan for the National Mall to increase the availability of space for new museums and memorials while adding residences and retail features that would make the city a more attractive place to live and work.[116] The plan was adopted by the Commission of Fine Arts on March 19, 2009, and approved by the NCPC on April 2, 2009.[117] The Monumental Core Framework Plan proposes demolishing the Forrestal Building and constructing apartment and office buildings along L'Enfant Promenade with retail and dining space at the street level to accommodate tourists and residents alike.[116][118]

There has also been an attempt to privatize the building. In October 2011, Representative Jeff Denham (R-Calif.) introduced legislation that would require the federal government to sell the Forrestal Building. The House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee voted 31–22 along party lines to approve the bill as an amendment to broader legislation designed to allow the federal government sell off or get rid of excess property.[119] The legislation did not pass.

On September 28, 2012, the General Services Administration issued a "Notice of Intent", asking for proposals from private developers to redevelop the Forrestal Building along with four others (the Department of Agriculture's Cotton Annex building, the Federal Aviation Administration's Orville Wright Federal Building, the Federal Aviation Administration's Wilbur Wright Federal Building, and the GSA National Capital Region Regional Office Building). GSA nicknamed the complex of five buildings "Federal Triangle South".[120] GSA said its goal for potential redevelopment would be to revitalize the neighborhood around the office buildings. The agency also said it would move forward with redevelopment along the lines suggested by the National Capital Planning Commission in its "Southwest Ecodistrict" plan.[121] The Southwest Ecodistrict plan, released in July 2012 and intended for approval in January 2013, proposed turning Federal Triangle South, L'Enfant Plaza, and several other nearby federal buildings into a high-density, environmentally-friendly, sustainable-living area.[122]

References

- National Capital Planning Commission, p. 3. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- "National Air and Space Museum (National Air Museum)." Buildings of the Smithsonian. The Smithsonian: 150 Years of Adventure, Discovery, and Wonder, 1996. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Gutheim and Lee, 2006, p. 266-267.

- Committee on the District of Columbia, 1978, p. 112.

- Gutheim and Lee, 2006, p. 260.

- Gutheim and Lee, 2006, p. 268.

- Von Eckardt, Wolf. "In All Its Dead-End Glory." Washington Post. May 5, 1973.

- Albrook, Robert C. "Zeckendorf to Start Detailed Slum Plans." Washington Post. October 14, 1954.

- Gutheim and Lee, 2006, p. 269-271.

- Zagoria, Sam. "Zeckendorf 'Ideal City' Is Described to Officials." Washington Post. February 17, 1954.

- Allbrook, Robert C. "Zeckendorf Mall Plan Approved." Washington Post. April 9, 1955.

- Historic American Buildings Survey, p. 86. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- "Air Museum Site Snags SW Planning." Washington Post. June 26, 1955.

- "Southwest Decision Is Postponed." Washington Post. November 29, 1955.

- Allbrook, Robert C. "Southwest Delay Laid Chiefly to Air Museum." Washington Post. December 15, 1955.

- Historic American Buildings Survey, p. 87. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- "Rep. Broyhill Offers Bills For Replacing 'Tempos'." Washington Post. March 4, 1954.

- Allbrook, Robert C. "Intelligence Agency Studies 3 Areas." Washington Post. April 15, 1955.

- "New Buildings Cost Less To Maintain Than Tempos." Washington Post. November 12, 1954.

- "GSA Is Planning Permanent Office In Southwest Area." Washington Post. June 5, 1955; Baker, Robert E. "6-Story Edifice Would Replace Some Existing Temporaries." Washington Post. July 23, 1955.

- Olesen, Don. "U.S. Building Program Will Eliminate All Tempos South of Constitution Ave." Washington Post. October 5, 1955.

- Historic American Buildings Survey, p. 104-105. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Bassett, Grace. "8 New Federal Buildings Indorsed by House Unit." Washington Post. July 20, 1956.

- Historic American Buildings Survey, p. 105. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- "Lease-Purchase Deferred." Washington Post. February 17, 1957.

- Eisen, Jack. "D.C. Temporary Buildings Appear Doomed to Permanency." Washington Post. April 27, 1958.

- Historic American Buildings Survey, p. 107. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Plumb, Tierney. "GSA Moves Forward on 200 C St. Renovation." Washington Business Journal. March 1, 2010. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Casey, Phil. "Federal Government On Big Building Spree." Washington Post. January 14, 1962.

- Historic American Buildings Survey, p. 106. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Subcommittee on Military Construction Appropriations, p. 363-366.

- "The Navy and D.C." Washington Post. November 29, 1958.

- Duscha, Julius. "City Center Still Seeking Navy Offices." Washington Post. September 7, 1959.

- "Fairfax Interests Navy As Headquarters Site." Washington Post. November 1, 1959.

- Lardner, Jr., George. "Smithsonian Revs Up For New Air Museum." Washington Post. August 2, 1963.

- Historic American Buildings Survey, p. 104. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- "All But 2 'Tempos' To Go in 5 Years Under GSA Plan." Washington Post. January 8, 1961.

- "New Defense Plans in SW Reactivated." Washington Post. May 19, 1961.

- Subcommittee on Military Construction Appropriations, p. 362-363.

- Eisen, Jack. "GSA Head Glad to See Tempos Go." Washington Post. March 15, 1961.

- "SW Defense Dept. Project Is Endorsed." Washington Post. June 14, 1961.

- "'Pentagon' Funds Win Support." Washington Post. June 23, 1961.

- "33,000 in Tempos Need Offices, Defense Says." Washington Post. July 17, 1961.

- Davis and Gruber, p. 82.

- Dibner, "Washington, D.C.: Trauma and Tenacity Prevailed in the Design of a Federal Office Building", Architectural Forum. January/February 1971, p. 46.

- Dibner, Joint Ventures for Architects and Engineers, p. 27.

- "Johnson Unveils Model of New Forrestal Building." New York Times. June 16, 1965.

- Bernstein, Adam. "David R. Dibner, Architect and GSA Executive, Dies at 83." The Washington Post. June 4, 2009. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- When the architectural contract for the structure was awarded in October 1961, the federal government had planned two L-shaped buildings snug against one another on both the east and west sides of 10th Street SW. See: Dibner, "Washington, D.C.: Trauma and Tenacity Prevailed in the Design of a Federal Office Building", Architectural Forum. January/February 1971, p. 46.

- Historic American Buildings Survey, p. 33. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Senate Reports, p. 143.

- Dibner, "Washington, D.C.: Trauma and Tenacity Prevailed in the Design of a Federal Office Building", Architectural Forum. January/February 1971, p. 48.

- Konsoulis, Mary. "The U.S. Commission of Fine Arts: 100 Years of Guiding Design in the Federal City." National Building Museum News. May 11, 2010. Archived June 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2012-06-23.

- "Tunnel to the Southwest." Washington Post. March 20, 1962.

- Dibner, "Washington, D.C.: Trauma and Tenacity Prevailed in the Design of a Federal Office Building", Architectural Forum. January/February 1971, p. 46-47.

- Dibner, "Washington, D.C.: Trauma and Tenacity Prevailed in the Design of a Federal Office Building", Architectural Forum. January/February 1971, p. 47.

- "Senate Voices Approval Of a 'Junior Pentagon'." Washington Post. August 3, 1962.

- Davis and Gruber, p. 21.

- Curtis, chapter 4. Archived 2012-04-16 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Von Eckardt, Wolf. "We Can Be Proud of 'Little Pentagon'." Washington Post. November 29, 1964.

- Dibner, "Washington, D.C.: Trauma and Tenacity Prevailed in the Design of a Federal Office Building", Architectural Forum. January/February 1971, p. 49.

- Subcommittee on Independent Offices, p. 1192.

- The façade of the Forrestal Building also is very similar to that of the 1975 J. Edgar Hoover Building, designed by Charles F. Murphy and Associates, and the 1977 Hubert H. Humphrey Building, also designed by Breuer.

- Office of Governmentwide Policy, p. 44. Accessed 2012-06-24.

- "L'Enfant Plaza Corp. Gets Southwest Tract." Washington Post. January 22, 1965.

- Meyer, Philip. "Uncle Sam Builds Again." Washington Post. May 29, 1965.

- "Blake Is Low On Forrestal Building Bid." Washington Post. July 4, 1965.

- "A Hole in the Ground Grows Bigger and Bigger." Washington Post. October 8, 1965.

- "Forrestal Building Site." Washington Post. January 4, 1966.

- "Delay on Forrestal Building Stalls SE Mall Construction." Washington Post. June 8, 1967.

- Prince, Richard. "Sights Amid The Tourist Attractions." Washington Post. April 15, 1969.

- Public Statements by the Secretaries of Defense, p. 9.

- Rothwell, enclosure 1, p. 1-2. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Rothwell, enclosure 1, p. 2. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Rothwell, enclosure 1, p. 3. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Rothwell, enclosure 1, p. 4. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Government Accountability Office, p. 13—145.

- Rothwell, enclosure 1, p. 5. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Subcommittee on Energy and Water Development, . 131.

- National Capital Planning Commission, p. 2. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- "Legislative Branch Appropriations Act, 2012" (PDF). Public Law 112-74, Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2012. United States Government Printing Office. 2011-12-23. p. 125 STAT. 1129. Retrieved 2012-03-02.

TRANSFER TO ARCHITECT OF THE CAPITOL

Sec. 1202. (a) Transfer.—To the extent that the Director of the National Park Service has jurisdiction and control over any portion of the area described in subsection (b) and any monument or other facility which is located within such area, such jurisdiction and control is hereby transferred to the Architect of the Capitol as of the date of the enactment of this Act.

(b) Area Described.—The area described in this subsection is the property which is bounded on the north by Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest, on the east by First Street Northwest and First Street Southwest, on the south by Maryland Avenue Southwest, and on the west by Third Street Southwest and Third Street Northwest. - Department of Energy, p. 7. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Nelson, p. 824.

- National Capital Planning Commission, p. 4. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Historic American Buildings Survey, p. 108. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Andelman, David A. "Designers of Office Space Widen Their Orbit." New York Times. July 19, 1970.

- Federal Energy Management Program, p. 1. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Department of Energy, p. 8. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Burchard, Hank. "Monumental Undertakings." Washington Post. July 3, 1992.

- Flanagan, p. 291.

- Department of Energy, p. 9. Accessed 201206-23.

- "Design Awards Given to 18 Federal Projects." New York Times. December 3, 1990. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- "Energy Department Installs Better Bulbs." Orlando Sentinel. October 11, 1993.

- Federal Energy Management Program, p. 6. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Federal Energy Management Program, p. 7. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- "U.S. DOE Installs SunPower Solar System." East Bay Business Times. September 9, 2008.

- "Energy Dept. Goes Green." New York Times. September 10, 2008.

- Lee, Jeffrey. "U.S. Dept. of Energy Inaugurates Headquarters' Solar Energy System." Echo Magazine. September 9, 2008. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Wald, Matthew L. "Energy Department Lags in Saving Energy." New York Times. July 7, 2010. Accessed 2012-06-29.

- Holusha, John. "Light Source To Replace Many Bulbs." New York Times. October 26, 1994; Suplee, Curt. "Energy Dept. Brings Dazzling Bulb to Light." Washington Post. October 21, 1994.

- National Capital Planning Commission, p. 5. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- National Capital Planning Commission, p. 8-14. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- National Capital Planning Commission, p. 15. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- National Capital Planning Commission, p. 16. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- National Capital Planning Commission, p. 24. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Von Eckardt, Wolf. "Forrestal Building Plan Is 'Fairly Happy' Ending." Washington Post. June 16, 1965.

- Forgey, Benjamin. "The D.C. Pei List: Losses and Gains." Washington Post. October 5, 2003.

- Huxtable, Ada Louise. "Architecture: The Federal Image." New York Times. June 27, 1965.

- von Eckardt, Wolf. "L'Enfant Plaza Is a Triumph." Washington Post. June 9, 1968.

- Hoffman, Ellen. "L'Enfant Plaza: Struggle for Urban Vitality." Washington Post. June 15, 1969.

- Historic American Buildings Survey, p. 107-108. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Moeller and Weeks, p. 60.

- DePillis, Lydia. "L'Enfant's Limbo." Washington City Paper. October 28, 2010. Accessed 2011-10-12.

- Dietsch, Deborah K. "Replacing D.C. Eyesores." Washington Business Journal. April 6, 2012. Accessed 2012-09-29.

- Luebke, Thomas. Commission of Fine Arts. "Forrestal Building." Letter to John D. Lazor, Director, Office of Headquarters Security Operations, U.S. Department of Energy. May 4, 2005. Accessed 2012-06-24.

- Rich, William. "South by West: Renovations Underway at L'Enfant Plaza." Archived 2011-07-11 at the Wayback Machine Hill Rag. January 2010.

- "Monumental Core Framework Plan." National Capital Planning Commission. No date. Archived 2011-10-15 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2011-02-27.

- Ruane, Michael E. "A Vision of Washington With Unfettered Views." Washington Post. July 10, 2008.

- Sernovitz, Daniel J. "Federal Bill Would Sell Department of Energy Building." Washington Business Journal. October 13, 2011. Accessed 2012-06-25.

- O'Connell, Jonathan. "GSA Proposes Massive Overhaul of Southwest Office Buildings Into a New Federal Triangle South." Washington Post. September 29, 2012. Accessed 2012-09-29.

- Neibauer, Michael. "GSA Eyes Sweeping Southwest D.C. Redevelopment." Washington Business Journal. September 28, 2012. Accessed 2012-09-29.

- "The SW Ecodistrict Initiative". National Capital Planning Commission. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to James V. Forrestal Building. |

- Committee on the District of Columbia. Subcommittee on Fiscal and Government Affairs. Amend Redevelopment Act of 1945 and Transfer U.S. Real Property to RLA: Hearings and Markups Before the Subcommittee on Fiscal and Government Affairs and the Committee on the District of Columbia. U.S. House of Representatives. 95th Congress, Second Session. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1978.

- Curtis, Nathaniel. "The Design Process." In The Rivergate (1968–1995): A 20th Century Masterpiece Destroyed By Louisiana's Gambling Blitz. Howard-Tilton Memorial Library. Tulane University. 2000. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Davis, Arthur Q. and Gruber, J. Richard. It Happened By Design: The Life and Work of Arthur Q. Davis. Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi, 2009.

- Department of Energy. Department of Energy Headquarters Facilities: Environmental Management System (EMS). Document number MA-40. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Energy, December 2005.

- Dibner, David R. Joint Ventures for Architects and Engineers. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1972.

- Dibner, David R. "Washington, D.C.: Trauma and Tenacity Prevailed in the Design of a Federal Office Building." Architectural Forum. January/February 1971.

- Federal Energy Management Program. Greening Project Status Report: DOE Headquarters. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Energy, February 2001.

- Flanagan, Jana Ricketts. Competitive Energy Management and Environmental Technologies. Lilburn, Ga.: Fairmont Press 1995.

- Government Accountability Office. Principles of Federal Appropriations Law. Vol. 3. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2008.

- Gutheim, Frederick A. and Lee, Antoinette J. Worthy of the Nation: Washington, D.C., From L'Enfant to the National Capital Planning Commission. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

- Historic American Buildings Survey. Southwest Washington, Urban Renewal Area. HABS DC-856. National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Washington, D.C.: Summer 2004. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Moeller, Gerard Martin, and Weeks, Christopher. AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington, D.C. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

- National Capital Planning Commission. Staff Recommendation: Forrestal Complex Security Enhancements. NCPC File No. 6367. Washington, D.C.: National Capital Planning Commission, April 28, 2005. Accessed 2012-06-23.

- Nelson, Michael. Congressional Quarterly's Guide to the Presidency. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly, 1989.

- Office of Governmentwide Policy. Office of Real Property. Governmentwide Real Property Performance Results. Evaluation and Innovative Workplaces Division. U.S. General Services Administration. December 1998. Accessed 2012-06-24.

- Public Statements by the Secretaries of Defense. Part 4: The Nixon and Ford Administrations (1969–1977). Paul Kesaris, ed. Cynthia Hancock, compiler. Frederick, Md.: University Publications of America, 1983. ISBN 0890935327

- Rothwell, Robert G. Review of the Consolidation of the Department of Energy in the Forrestal Building. Document number LCD-78-J26; B-95136. Washington, D.C.: U.S. General Accounting Office, May 9, 1978.

- Senate Reports. Vol. 3. Miscellaneous Reports on Public Bills, III. U.S. Congress. 87th Cong., 2d sess. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1962.

- Subcommittee on Energy and Water Development. Energy and Water Development Appropriations for 1981. Committee on Appropriations. U.S. House of Representatives. 96th Cong., 2d sess. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1980.

- Subcommittee on Independent Offices. Independent Offices Appropriations for 1964. Committee on appropriations. U.S. House of Representatives. 88th Cong., 1st sess. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1963.

- Subcommittee on Military Construction Appropriations. Military Construction Appropriations for 1966. Part 3. Committee on Appropriations. U.S. House of Representatives. 89th Cong., 1st sess. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1965.