James S. Holmes

James Stratton Holmes (2 May 1924 – 6 November 1986) was an American-Dutch poet, translator, and translation scholar.[1] He sometimes published his work using his real name James S. Holmes, and other times the pen names Jim Holmes and Jacob Lowland. In 1956 he was the first non-Dutch translator to receive the prestigious Martinus Nijhoff Award, the most important recognition given to translators of creative texts from or into Dutch.

James S. Holmes | |

|---|---|

James Stratton Holmes | |

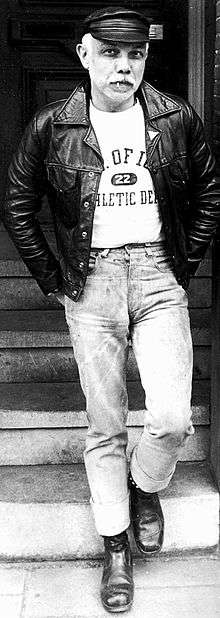

James S. Holmes in front of his room in the Weteringschans district in Amsterdam (July 16, 1981. Credit: Tom Ordelman) | |

| Born | 2 May 1924 |

| Died | 6 November 1986 Amsterdam, the Netherlands |

| Cause of death | AIDS |

| Other names | Jim Holmes Jacob Lowland |

| Citizenship | American |

| Occupation | Poet, translator, translation scholar |

| Home town | Collins, Iowa |

| Partner(s) | Hans van Marle |

| Awards | Martinus Nijhoff Award |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | Translation Studies |

| Notable works | The name and nature of translation studies (1975) |

Childhood and education

The youngest of four siblings, Holmes was born and raised in a small American farm in Collins, Iowa. In 1941, after finishing high school, he enrolled in the Quaker College of Oskaloosa, Iowa. After a study journey of two years, he did a middle school teaching internship in Barnesville, Ohio.[2] Some years later, after refusing to go on military service for the American Army or, alternatively, civil service, Holmes was sentenced to a 6-month jail term. Upon his release, he went back to studying: first at William Penn College, and later at Haverford College in Pennsylvania.

In 1948, after obtaining two degrees, one in English and one in History, he continued his studies at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, one of the well-known Ivy League Schools, where the following year he became a research doctor. In the meantime he had written and published his first poems and had carried out some occasional editorial work. From there, in no time, poetry became his great passion.

1949: The Netherlands

In 1949 Holmes interrupted his studies to work as a Fulbright exchange teacher in a Quaker school in the Eerde Castle, near Ommen, in the Netherlands. At the end of the school year he decided not to return to the United States, but to stay and visit the country. It was in this way that, in 1950, he met Hans van Marle. To Holmes, the relationship with Van Marle soon became something highly important that brought him to making the choice never to go back to the United States, and to move permanently to Amsterdam. For the next two years, Holmes attended Nico Donkersloot's Dutch language course at the Universiteit van Amsterdam, and published in 1951 his first poetry translation.[2]

1952: Passion becomes profession

Translating poetry became Holmes' main occupation, and, after his appointment as an associate professor in the Literary Science faculty at the Universiteit van Amsterdam, translation was his main source of income. Together with his partner Hans van Marle, he translated not only poetry, but also documents about Indonesia and Indonesian poetry in English. His reputation as a translator grew, and in 1956 he was granted the Martinus Nijhoff Award for his translations into English, becoming the first foreigner to receive it.[3] In 1958, when the legendary English magazine Delta was founded, exclusively devoted to the culture of the Netherlands and Belgium, James Holmes became its poetry editor and often took care of the translations of contemporary Dutch poetry in English.[4] It was a time in which Holmes particularly devoted himself to the poetry of the "Vijftigers" [an important group of Dutch poets of the 50s – 'vijftig' in Dutch] and of the "post-Vijftigers", poetry of complex comprehension, and therefore, hard to translate.

Translation Studies

When the Literary Science faculty of the Universiteit van Amsterdam decided in 1964 to create a Department of Translation Studies, Holmes was invited to contribute as an associate professor. He not only had the needed scholarly background, but over time he had acquired many theoretical notions as well, as well as considerable practical experience as a translator. He created courses for the Institute of Interpreters and Translators, which was later integrated into the Institute of Translation Studies of the Universiteit van Amsterdam. Holmes' paper "The Name and Nature of Translation Studies" (1972)[5] is widely recognized as founding Translation Studies as a coordinated research program. Holmes' many articles on translation made him one of the key members of Descriptive Translation Studies, and still today he is frequently cited in the bibliographies in this field.

Appreciation for "Awater" by Nijhoff and the Nobel Prize

One of the most extraordinary examples of Holmes' bravery was his translation of the very long poetic piece "Awater" by Martinus Nijhoff, a work that gained attention both in the Netherlands and abroad. The English translation of this piece contributed to the fame of both the poet and the translator.[6] After having read "Awater," Nobel laureates in Literature T.S. Eliot and Iosif Aleksandrovič Brodskij expressed their appreciation. Eliot said that if Nijhoff had written his works in English instead of Dutch, he would have become a global success, while Brodskij bluntly stated that "Awater" was one of the most beautiful poetry works he had ever read.

Columbia University establishes the James S. Holmes Award

Holmes went on to translate dozens of works from Dutch and Belgian poets, and in 1984 he received the Flemish Community Translation Award (Vertaalprijs van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap), once more the first foreigner to receive it.

His masterpiece was, undoubtedly, the translation of the impressive collection Dutch Interior, a considerable anthology of post-war poetry, published in 1984 in New York by the Columbia University Press. Holmes was one of the most important editors of this classic text, and also translated many of the poetry works present in that collection.

His contribution into raising awareness of Dutch poetry into the Anglo-Saxon world was recognised by the Translation Center of Columbia University when it decided to establish a new award for Dutch translators called the James S. Holmes Award.

Associations, committees, orders and editions

In the Netherlands, Holmes always felt welcome, not only because of the vast array of acquaintances that had come from his works as a poet and translator, but especially from the many friendships born in the gay spheres of Amsterdam. His American accent and the fact that he continued making mistakes with the Dutch definite article was no reason for him to be considered a foreigner or treated as such.

Therefore, he began taking part in many varied committees and orders, he joined the editorial offices of the Dutch-Belgian youth magazine Gard Sivi and contributed to literary magazines such as Literair Paspoort, De Gids, De Nieuwe Stem, Maatstaf and De Revisor.

He was an active member of the Dutch and the International PEN Club, the Writers' Association, the Dutch Literature Association and the UNESCO National Commission. He also became a participant in the committee of the Foundation for the Promotion of the Translation of Dutch Literary Works abroad, the Dutch Association of Translators, the Writers' Organization, School and Society, and was an honorary member of the Association of Flemish Scholars.[7]

Workshops, festivals and demonstrations

In 1967 Holmes organized the "Poetry for Now" demonstration, at the famous Concertgebouw Theater in Amsterdam. During that event, the organizers covered the city with thousands of posters with translated poetry. After many years it was still possible to find posters stuck on bus stops, near the entrances of apartment blocks, in streetlights, on gates or level crossings. In the 70s Holmes began managing a workshop on poetry translation which attracted many students of various university faculties. Some of those students eventually became, in turn, famous poetry translators.

Holmes participated in every poetry demonstration, such as for example the Poetry International in Rotterdam and the One World Poetry in Amsterdam. Sometimes he recited poetry, sometimes he was a coordinator or gave conferences on translation, but he always made himself actively present. As soon as he had a chance, he organized conferences abroad on the topic of translated Dutch poetry, as for example at the Library of Congress in Washington.

Poetry Gone Gay

In 1984, in the midst of the One World Poetry demonstration, he organized an evening called "Poetry Gone Gay", in which he read some of his works dealing with homosexuality and eroticism. He found it extremely liberating to be able to show that part of his personality to the audience, and especially to obtain recognition and approval from it. Holmes loved to display his sexual orientation, not only in his poetry, but especially in his outfits and accessory choice. In the last years of his life he created the character that we see in the picture on this page: a middle-aged man with short white-as-snow hair, jeans with a studded waist, studded bracelets, a pink triangle on the flap of his jacket, a large handful of keys attached to the jeans, and the tip of a pink handkerchief sticking out of the back pocket. This same sexual freedom was, probably, the cause of his premature death caused by AIDS.[8] However, Holmes was aware of the dangers linked to his extravagant lifestyle, and openly declared that they had never, in any way, influenced his choices in life.

During his memorial, which was crowded, his life partner and great love Hans van Marle concluded his farewell speech with a short excerpt of the famous "Meditation XVII" of Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions, a metaphysical piece written in 1624 by John Donne, of which Ernest Hemingway, in 1940, extracted the title of his famous novel For Whom The Bell Tolls:

'No man is an island entire of itself; every man

is a piece of the continent, a part of the main;

(...)

any man's death diminishes me,

because I am involved in mankind.

And therefore never send to know for whom

the bell tolls; it tolls for thee. '

Selected bibliography

Poetry

- Jim Holmes, Nine Hidebound Rimes. Poems 1977 (Amsterdam, 1978).

- Jacob Lowland, The Gay Stud's Guide to Amsterdam and Other Sonnets (Amsterdam, 1978; second edition 1980).

- Jacob Lowland, Billy and the Banquet (Amsterdam, 1982).

- James S. Holmes, Early Verse 1947-1957 (Amsterdam/New York, 1985).

Poetry translation

- Martinus Nijhoff, Awater. A Long Poem, With a Comment on Poetry in Period of Crisis (Amsterdam, 1992).

- Paul Snoek and Willem M. Roggeman (editor), A Quarter Century of Poetry from Belgium (Flemish Volume) (Bruxelles/L'Aja, 1970).

- Peter Glasgold (ed.), Living Space (New York, 1979).

- Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Scott Rollins (editor), Nine Dutch Poets (San Francisco, 1982).

- James S. Holmes and William Jay Smith (editor), Dutch Interior. Postwar Poetry from the Netherlands and Flanders (New York, 1984).

Many translations in magazines such as:

- Modern Poetry in Translation (Monographical issue on the Netherlands 27/28, 1976)

- Delta

- Atlantic

- Carcanet

- Chelsea Review

- Poetry Quarterly

Scientific works and articles

- James S. Holmes et al. (editor), The Nature of Translation. Essays on the Theory and Practice of Literary Translation (L'Aja/Bratislava, 1970).

- James S. Holmes et al. (editor), Literature and Translation. New Perspectives in Literary Studies (Leuven, 1978).

- James S. Holmes, Translated!. Papers on Literary Translation and Translation Studies (Amsterdam, 1988).

References

- Lambert, José (1995). "Translation, Systems and Research: The Contribution of Polysystem Studies to Translation Studies". TTR : traduction, terminologie, rédaction (in French). 8 (1): 105. doi:10.7202/037199ar. ISSN 0835-8443.

- Weissbort, Daniel (2016). Translating Poetry: The Double Labyrinth. New York: Springer. p. 58. ISBN 9781349100897.

- Möhlmann, Thomas (2009). "Awater in the UK". Literature from the Low Countries. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- Boase-Beier, Jean (2017). Translating Holocaust Lives. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781474250290.

- Holmes, James S. (1972/1988). The Name and Nature of Translation Studies. In Holmes, Translated! Papers on Literary Translation and Translation Studies, Amsterdam: Rodopi, pp. 67–80.

- "Awater". Carcanet Press. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- Holmes, James (1988). Translated! Papers on Literary Translation and Translation Studies. Amsterdam: Rodopi. p. 3. ISBN 90-6203-739-9.

- "James Stratton Holmes". AIDS Memorial Nedderlands. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

External links

- Site of the Digitale Bibliotheek voor de Nederlandse Letteren (DBNL) Digital Library of Dutch Literature