James Hall (historian)

James Hall (20 February 1846 – 6 October 1914) was an English antiquary, historian and schoolteacher, best known for his history of the Cheshire town of Nantwich, which remains among the principal sources for the town's history. He also edited accounts of the English Civil War and documents relating to Combermere Abbey. Another work on the history of Combermere Abbey, Newhall and Wrenbury was never published; its manuscript has been lost. Hall is commemorated in Nantwich in several ways, including a street named for him.

.jpg)

Life

Early life and education

Hall was born in the Brayford Head district of Lincoln on 20 February 1846.[1][2] His father, also James Hall (born 1816), captained a steam packet which plied the River Witham between Lincoln and Boston, and his paternal grandfather, William Hall (born 1765), had been a waterman in Lincoln. His mother, Elizabeth, was the daughter of George Markham, a farmer from the village of Treswell in Nottinghamshire. They had married in 1843; Hall was the second of their ten children, five of whom died in infancy, and their only surviving son.[2] He grew up in Grantham Street in the centre of the city of Lincoln, where the family moved after his father gave up working on the river to become a rate collector and manager of the Lincoln and Lincolnshire Building Society.[2]

The family were Wesleyan Methodists and worshipped at Clasketgate Chapel, where Hall's father taught at the Sunday school. From 1854, Hall attended the Wesleyan Day School in Grantham Street (later in Rosemary Street), rising to become a pupil–teacher. He received tuition on the piano from the well-known teacher C. A. Ehrenfechter, and was also taught the organ by the Clasketgate Chapel organist.[2] Deciding to make his career in teaching, he joined the Wesleyan Training College at Westminster in 1864, graduating first in his year in English two years later.[2]

Educator

The Wesleyan Methodist Chapel of Nantwich in Cheshire was seeking a headmaster in 1866 for its elementary Day School to succeed the retiring Mr Mobbs; they required an incumbent who could also play the organ at the chapel. Twenty-years old Hall was appointed, and took up the position on 7 January 1867.[2] He was to spend the rest of his life in Cheshire.[1] The school had been founded in 1840, and stood on Hospital Street, opposite the chapel. In 1873, during Hall's time there, subjects taught included religion and reading, and both boys and girls attended.[3] The present building on the site dates from 1909; the old school burned down in January 1908.[3][4]

On 9 June 1870, Hall married Elizabeth Goy, daughter of Matthew Goy, a builder who lived near the Hall family in Grantham Street. Elizabeth later acted as Hall's secretary and proofreader for his history, and also administered his private school. The couple had four children: two daughters, the elder of whom, Margaret, assisted in school administration, and two sons, the artist Walter J. Hall (born 1875/6) and George (born 1883).[1][5][6]

In 1874, Hall was appointed the first headmaster of the new Board School at Willaston, near Nantwich, built under the Education Act of 1870.[1][4] Although the school was not formally opened until 28 June 1875, he began to teach 40 boys in the Congregational Schoolroom on Church Lane from the beginning of that year. He moved his growing family to rented accommodation in Broad Street (now Wellington Road), near the station, until the schoolhouse at Willaston was completed in March 1876. The number of pupils grew rapidly, with 132 the month after the school opened and later reaching 230; up to five other teachers were employed. In addition to the required curriculum, he taught singing, drawing and Latin.[4]

Local historian

According to Walter Hall, his father's interest in local history was kindled in the early 1870s by Thomas Bolton (died 1877), a Nantwich boot-and-shoe manufacturer whose tales of Nantwich in the first half of the century piqued Hall's interest. His first publication was a Christmas tale, written for Bolton, which appeared under the pseudonym "Peter Plover".[5] While living at Willaston, he also became a friend of the antiquary John Parsons Earwaker, FSA, the first volume of whose history of East Cheshire appeared in 1877.[7][8]

Hall started work on his history of Nantwich in the mid-1870s; it took nearly a decade to complete. The research included many visits to churches to document their architecture and to transcribe church registers and memorial inscriptions; he also consulted many library collections, travelling as far afield as Oxford and London.[4][7] The text was finished on 10 December 1883, the 300th anniversary of the Great Fire of 1583 that destroyed much of the town. The manuscript ran to 1154 foolscap sheets; indexing it took a further month.[4] Walter Hall states that shortly after the book's publication, the Society of Antiquaries offered to confer its fellowship on Hall, but his father declined the honour.[7]

Musical activities

Hall was the organist of the Nantwich Wesleyan Methodist Chapel in 1867–75 and 1882–1907. He composed five hymns and three other works for the Nantwich choir. With Alfred Withinshaw, he founded the Choral Union of the Wesleyan Methodist choirs of Nantwich, Crewe and Market Drayton in 1884, and organised three music festivals in 1884–85.[9]

Difficulties in later life

In 1885, soon after the publication of Hall's History, Willaston Board School received an "unsatisfactory" rating in its government inspection. In his biography of his father, Walter Hall claims that there was "certainly no neglect of duty as regards [Hall's] teaching," and associates the poor report with insinuations circulating among some local residents that his father had been neglecting his headmaster's duties in favour of writing his History.[4] Walter cites contemporary local newspaper articles in support of his father, concluding that his work had been "widely appreciated."[4] After an appeal failed, Hall resigned, leaving the post in June 1886.[4]

He moved back into Nantwich, initially renting 84 Welsh Row, and decided to open a private senior school for boys. He started to build Lindum House, a schoolroom and substantial master's house on Wellington Road. On 29 September 1886, while the buildings were still under construction, he opened the school on Welsh Row with six pupils. The new schoolroom was completed by the end of the year; by January 1887, the school had 17 pupils. The family moved into the master's house in April.[10] Financial problems occurred from the outset when Hall fell into dispute with his architect, incurring legal expenses of more than £250 which meant that he remained in debt until 1901. Despite employing a drillmaster and offering French tuition, pupil numbers rose only slowly and then declined, with the school never having more than 35 pupils.[10]

By 1905, with only 12 pupils remaining, it was obvious that the venture had failed. Hall tried to sell Lindum House in May of that year, but it took two years for an acceptable offer to be received. The school closed on 19 June 1907.[11]

Retirement, death and legacy

In September 1907, Hall moved to Saughall Road in the north west of Chester.[11] He remained active in retirement, joining the Chester Archaeological Society and the Society of Literature and Art, and undertaking cataloguing projects for the Corporation of Chester, Chester Archaeological Society and the Tollemache family, among others.[12][13]

His health declined in 1909–10; the condition recurred in February 1914, and the following September, his health deteriorated further. He died in Chester on 6 October 1914, and was buried at Chester New General Cemetery.[12]

A posthumous portrait of Hall, painted by his son Walter J. Hall, was presented to the town of Nantwich in 1943. It formerly hung in the Free Library and is now displayed in the main gallery of Nantwich Museum.[1][14] The portrait depicts him sitting in front of two pictures of churches, Lincoln Cathedral and St Mary's Church, Nantwich.[1] At this time, Walter Hall wrote four biographical articles, published in the Nantwich Guardian in 1944 and subsequently collected into a brief biography by J. Lodge, headmaster of Nantwich and Acton Grammar School.[14] He is also commemorated by a tablet in the porch of St Mary's Church, erected in 1946, the centenary of his birth, by Percy Corry, also a local historian. It describes him as "The Historian of Nantwich."[1] A street in Nantwich is named for him.[15]

Historical work

History of Nantwich

Hall is best known for his history of Nantwich.[16] The first history of the town was published anonymously by the Reverend Joseph Partridge, master of the Nantwich Blue Cap Charity School, in 1774.[17][18] A second history by John Weld Platt, published in 1818, is dismissed by Hall as "little more than an enlarged and better arranged edition of the former work," which fails to acknowledge its source.[18][lower-alpha 1] He calls Platt's description of Nantwich Castle "purely fictitious."[19]

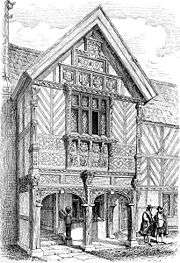

Hall's history, entitled A History of the Town and Parish of Nantwich, or Wich-Malbank, in the County Palatine of Chester but usually referred to as Hall's History of Nantwich, was completed in December 1883. The first edition of 350 copies was financed by subscription; it was privately printed by local printer Thomas Johnson, bound by Macmillan and Co. in Manchester and distributed early in 1884.[7] Nearly four times the length of Platt's work, it covers the period from the Domesday survey of 1086 to the date of publication, and additionally includes the nearby townships of Alvaston (now part of Worleston), Willaston and Woolstanwood. There are 29 line illustrations, some of which are not credited and might have been drawn by the author.[20]

The book received reviews in national and local periodicals, including one in The Athenaeum on 7 March 1885, which praised the meticulous referencing and described the history as "able, clear and succinct" and its author as "conscientious and careful."[21] Despite the positive reception, it was not reprinted in Hall's lifetime. Several replica editions have since been published, the first in 1972, and various online editions are now available. Though in part outdated,[22] Hall's History remains the authoritative history of the town and is frequently cited by modern works.[lower-alpha 2] Cheshire County Council and English Heritage stated in a 2003 report that Hall's history, with George Ormerod's history of Cheshire, are the "chief sources for the history of Nantwich."[25]

Civil War journals

The great majority of Hall's other works as an author and editor relate to the history of Cheshire. He edited two accounts of the English Civil War in the county as Memorials of the Civil War in Cheshire and the Adjacent Counties by Thomas Malbon and Providence Improved by Edward Burghall, published in 1889.[26] Thomas Malbon's Civil War journal was included in the Cowper manuscript collection of Condover Hall, to which Hall gained access from its owner, Reginald Cholmondeley. "Providence Improved" by Edward Burghall, the Puritan rector of St Mary's Church, Acton, incorporates a version of part of Malbon's writing. Hall gained access to the text from his friend, J. P. Earwaker. Hall's edition places the two diaries side by side, with his annotations, and also includes biographies of the two men.[27][28] C. B. Phillips, writing in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, describes Hall's edition of "Providence Improved" as "well printed" but considers Hall's characterisation of Burghall's reworking of Malbon as plagiarism to "miss the point."[28]

Combermere Abbey

Hall also edited "The Book of the Abbot of Combermere", published in 1896. The book is a collection of leases and rent rolls from 1289–1529 relating to Combermere Abbey, which owned a quarter of Nantwich, copied by the final abbot, John Massey, and others.[29] Hall was granted access to the documents by Robert Wellington Stapleton-Cotton, Viscount Combermere, the abbey's owner.[30]

Stapleton-Cotton later gave him access to other material relating to the abbey – which resulted in the manuscript, The History of Combermere, Newhall Township and the Village of Wrenbury – but died in 1898 before this history could be completed. It was never published, as Hall had been relying on the viscount's sponsorship of the project. Walter Hall attempted to bring the work out in 1939, but was prevented by paper shortages during the Second World War.[30] At this date, the Reverend A. L. Moir, vicar of St Mary's and St Michael's, Burleydam, also attempted to obtain the manuscript for publication without success.[31] The manuscript, which ran to 780 foolscap sheets and covered many of the small settlements near the abbey, has since been lost.[16][30][31]

Other

Hall published articles in many historical and literary journals, including The Athenaeum, Notes and Queries, Palatine Note Book, Local Gleanings of Lancashire and Cheshire and the Journal of the Chester Archaeological Society, and also a chapter in the book Memorials of Old Cheshire (1910).[7][12][27] The last gave rise to controversy as Hall inaccurately stated that Tabley Old Hall was "ruinous" when at that date it remained in reasonable repair; its owner, Lady Leighton-Warren, complained and it emerged that Hall, whose health was failing, had based his opinion on postcard images without visiting.[12] Hall gave lectures to many local societies on topics ranging across music and literature as well as local history.[27] Thirty volumes of his unpublished notebooks are archived in The National Archives.[16] These and other unpublished notes include research on medieval architecture, misericords in local churches, Acton and Dorfold Hall, and the history of the Delves family of Doddington Castle.[16][32]

He served as the honorary local secretary for Nantwich of The Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire from around 1889 until his death, and was elected to the council of the Chester Archaeological Society in 1908.[12][33][34]

Selected publications

- A History of the Town and Parish of Nantwich, or Wich-Malbank, in the County Palatine of Chester (1883)

- Memorials of the Civil War in Cheshire and the Adjacent Counties by Thomas Malbon and Providence Improved by Edward Burghall (Lancashire and Cheshire Record Society; 1889) [as editor]

- "The Book of the Abbot of Combermere 1289–1529" (The Record Society; 1896) [as editor]

- "Cheshire and its Families" in Memorials of Old Cheshire, Barber E, Ditchfield PH, eds, pp. 194–206 (George Allen & Sons; 1910)

Notes and references

- Platt JW. The History and Antiquities of Nantwich, in the County Palatine of Chester at Google Books (Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown; 1818)

- For example, Roland Morant (1996) acknowledges "J. Hall whose volume on the history of Nantwich ... though written many years ago is still an important resource document."[23] J. Howard Hodson (1978) ranks it in the top three older books on individual Cheshire towns.[24] The work is a source for volumes 5–7 and 9 of the History of Cheshire series, and five articles in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- Nantwich Museum: James Hall Archived 13 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 3 April 2013)

- Hall WJ, pp. 6–7

- "The Methodist Church in Nantwich", Website, Nantwich Methodist Church, archived from the original on 8 March 2012, retrieved 4 April 2013

- Hall WJ, pp. 8–10

- Hall WJ, pp. 7–8

- Hall WJ, p. 22

- Hall WJ, pp. 10–11

- Sutton CW (revd Crosby AG). 'Earwaker, John Parsons (1847–1895)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press; 2004) (accessed 5 April 2013)

- Hall WJ, pp. 15–16

- Hall WJ, p. 13

- Hall WJ, p. 19

- Hall WJ, p. 20–23

- B. E. Harris (1978), "A nineteenth-century Cheshire historian: John Parsons Earwaker 1847–1895" (PDF), Journal of the Chester Archaeological Society, 61: 51–59

- Hall WJ, p. 3

- Cheshire East, Cheshire West & Chester: Interactive Mapping: Nantwich (accessed 3 April 2013)

- The National Archives: Notebooks of James Hall (accessed 3 April 2013)

- Sutton CW (revd Skedd SJ). 'Partridge, Joseph (1724–1796)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press; 2004) (accessed 3 April 2013)

- Hall J, p. xiii

- Hall J, p. 16

- Hall J, pp. i–xvi

- Hall WJ, pp. 11–13

- Beck, p. 61

- Morant, p. xi

- Hodson, p. 112

- Cheshire County Council, English Heritage. Cheshire Historic Towns Survey: Nantwich: Archaeological Assessment (2003)

- Cheshire Campaign 1643–4: Bibliographic Note Archived 21 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine (1959) (accessed 3 April 2013)

- Hall WJ, pp. 16–17

- Phillips CB. 'Burghall, Edward (bap. 1600, d. 1665), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004) (accessed 6 April 2013)

- Hall J, ed. (1896), "The Book of the Abbot of Combermere 1289–1529", Miscellanies, Relating to Lancashire and Cheshire, The Record Society

- Hall WJ, pp. 18–19

- Latham 1999, ed., p. 49

- Latham 1995, ed., pp. 7, 149

- The Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire: Preliminary List of Honorary Local Secretaries: 1889 (accessed 3 April 2013)

- The Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire: Report, &c.: 1914 (accessed 3 April 2013)

Sources

- Beck J. Tudor Cheshire. A History of Cheshire, Vol. 7 (Series Editor: JJ Bagley) (Cheshire Community Council; 1969) (ISBN 0-903119-02-1)

- Hall J. A History of the Town and Parish of Nantwich, or Wich-Malbank, in the County Palatine of Chester (E.J. Morten; 1972) (ISBN 0 901598 24 0)

- Hall WJ. James Hall: 1846–1914: A Short Biography (1946; reprinted from the Nantwich Guardian; 29 January – 18 February 1944) (OCLC 499765659)

- Hodson JH. Cheshire, 1660–1780: Restoration to Industrial Revolution. A History of Cheshire Vol. 9 (Series Editor: JJ Bagley) (Cheshire Community Council; 1978) (ISBN 0 903119 11 0)

- Latham FA, ed. Acton (The Local History Group; 1995) (ISBN 0-9522284-1-6)

- Local History Group, Latham FA, ed. Wrenbury and Marbury (The Local History Group; 1999) (ISBN 0 9522284 5 9)

- Morant RW. Monastic and Collegiate Cheshire (Merlin Books; 1996) (ISBN 0 86303 729 1)