James Franklin Hyde

James Franklin Hyde (11 March 1903 – 11 October 1999) was an American chemist and inventor. He has been called the “Father of Silicones” and is credited with the launch of the silicone industry in the 1930s. His most notable contributions include his creation of silicone from silicon compounds and his method of making fused silica, a high-quality glass later used in aeronautics, advanced telecommunications, and computer chips. His work led to the formation of Dow Corning, an alliance between the Dow Chemical Company and Corning Glass Works that was specifically created to produce silicone products.

James Franklin Hyde | |

|---|---|

| Born | 11 March 1903 |

| Died | 11 October 1999 (aged 96) |

| Nationality | United States |

| Alma mater | Syracuse University University of Illinois Harvard University |

| Partner(s) | James F. Hyde Ann H. Hyde Sylvia Hyde Schuster |

| Awards | Perkin Medal (1971) J.B. Whitehead Award |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry |

Life

Early years and education

James Franklin Hyde was born in Solvay, New York on March 11, 1903. He attended Solvay High School and graduated on June 25, 1919 at the age of 16.[1] He was partly encouraged by one of his science teachers to enter into the field of science.

After high school, Hyde attended Syracuse University, where he earned both his Bachelor of Arts and Master of Arts degrees. Afterwards, he earned a Ph.D. in organic chemistry at the University of Illinois. He then completed his academic education at Harvard University, where he was granted a post-doctoral fellowship under Dr. James Bryant Conant. He also received an Honorary Doctor of Science degree from Syracuse University.

Research

In 1931, Hyde became the first organic chemist to accept a position at Corning Glass Works (now Corning Incorporated). He was hired to investigate the new plastics that challenged the glass industry. Hyde had studied Kipping and Ladenburg’s work in the field of organic silicon chemistry and sought to find a flexible, high temperature binder for the glass fibers that would allow for an increase in service temperature for insulating materials. He followed Kipping’s procedure for creating organic silicon compounds by using Grignard’s magnesium-containing reagent and eventually synthesized a fluid that hardened to a rubbery mass. This new composite was one of the first Class H insulators and made it possible for Corning to produce high temperature motors and generators.[2] This silicone was used in ships and planes during World War II, as cable and wire insulation, in aeronautical equipment, and in window insulation. Future versions of this silicone would be used in breast implants and in prosthetic heart valves.[3]

In 1934, Hyde used a method called “flame hydrolysis” to create fused silica, an impurity-free glass. This method involved heating silicon and oxygen by running silicon tetrachloride gas through an oxygen flame. The result was a fine, glassy powder of silicon dioxide, which could be pressed into various shapes. Hyde’s method proved to be a breakthrough in glass production.

Fused silica was initially used in mirrors, telescopes, radar, and later in spacecraft windows and fiber optics. Corning researchers used this fused silica when they invented optical fiber in 1970, which provided faster transmission speeds than copper wires did. Fused silica has also made the miniaturization of computer chips possible, as it is used in high transmission microlithographic lenses.

Decades later, Hyde remarked that “[he was] surprised at some of the things [fused silica] has gone into, but [he was] not surprised at the versatility of such a beautiful and useful material.”[4] He claims that his inspiration for developing his fused silica was the telescope that was being built at the Palomar Observatory in California. However, he was too late to influence this telescope project, which was built by Corning using Pyrex, a glass it developed in 1915.

On August 27, 1934, Hyde filed a patent application with the United States Patent Office for “[his] method of making a transparent article of silica.” This patent was granted to him on February 10, 1942.[5]

Hyde’s work led to the formation of the Dow Corning Corporation in 1943, a joint venture by Corning Glass Works and the Dow Chemical Company to produce silicone products. Dr. William Armistead, former vice chairman for technology at Corning Glass Works, not only recognizes Hyde as “the father of silicones,” but also calls him “the father of Dow Corning.” The Dow Corning Corporation now operates in more than 20 nations around the world, with $4.94 billion in revenue in 2007.[6]

In 1951, Hyde was appointed the position of senior research scientist for basic organosilicon chemistry at Dow Corning. He had previously held the position of manager of the Organic Chemistry Research Laboratory at Corning from 1938 until 1951.

Later years

In 1973, Hyde retired but continued to serve Dow Corning as a research consultant.

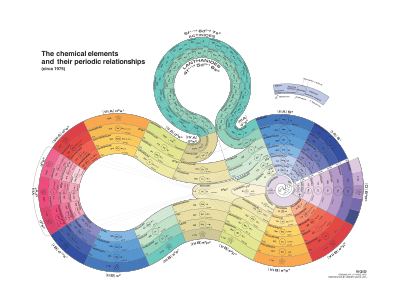

In 1976, he published in the student magazine Chemistry an alternative periodic table of his own design, which allots a central position to the element silicon.[7]

Since 1992, the J. Franklin Hyde Scholarship in Science Education has been awarded annually by Dow Corning and the Dow Corning Foundation to outstanding students who plan to teach science at the secondary level.[8]

In 2000, Hyde was nominated by Corning Incorporated and inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

For the remainder of his days, Hyde lived alone on Marco Island, Florida. His three children visited him regularly. He is proud of his accomplishments during his career and says that “it gives [him] a great satisfaction that [he] did something useful in life.”

Dr. James Franklin Hyde died in his Florida home on October 11, 1999, at the age of 96, with over 100 patents held in his name while at Corning Incorporated.

Personal life

In 1930, James Franklin Hyde was married to his wife Hildegard. He has three children: James F. Hyde, Ann H. Hyde, and Sylvia Hyde Schuster.

Hyde’s wife Hildegard died in 1991. He said to the New York Times: “When you lose someone close to you like that, you never really get over it.”

Patents

- Hyde, U.S. Patent 2,272,342, "Method of making a transparent article of silica"

Notes

- "Solvay High School 1920 Graduation Classes". Archived from the original on 2012-02-19. Retrieved 2008-11-14.

- "Silicones 4. Corning and the First Silicones for High Temperature Insulation". Archived from the original on 2008-10-21. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- "James Franklin Hyde". Plastics Academy Hall of Fame. 2004-03-29. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- "In 1934, It Was Plain to See, New Glass Had Bright Future". New York Times. 1998-11-26. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- "James Franklin Hyde". Inventor of the Week Archive. July 2004. Archived from the original on 2004-08-03. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- "Dow Corning Company Profile".

- Benfey, Theodor. "The Biography of a Periodic Spiral" (PDF). American Chemical Society - Division of the History of Chemistry. Bulletin for the History of Chemistry. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- "J. Franklin Hyde Scholarship".

References

- Goosey, Martin T. Plastics for Electronics. Coventry: Springer, 1999. Page 26.

- Highlights from the history of Dow Corning Corporation, the silicone pioneer Dow Corning Silicones

- Silicone

- J. Franklin Hyde, the Father of Silicones

- Peterson, Julie K. Fiber Optics Illustrated Dictionary. Florida: CRC Press, 2002.

- A Future Full of Light

- Inventors Hall brings energy to Akron

External links

- “J. Franklin Hyde, 96, the ‘Father of Silicones’.” New York Times. https://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D06E1D91E30F935A25753C1A96F958260

- “Highlights from the history of Dow Corning Corporation, the silicone pioneer.” http://www.dowcorning.com/content/publishedlit/01-4027-01.pdf

- “A Future Full of Light.” IEEE Journal. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?arnumber=00902175