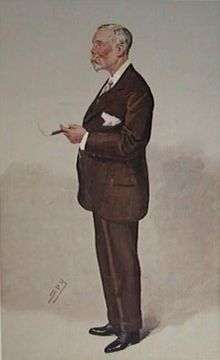

James Charles Inglis

Sir James Charles Inglis (9 September 1851 – 19 December 1911) was a British civil engineer.[1]

James Charles Inglis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 9 September 1851 |

| Died | 19 December 1911 (aged 60) |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Engineering career | |

| Discipline | Civil, |

| Institutions | Institution of Civil Engineers (president) |

Career

He began his engineering career in Glasgow, before moving to London in 1871, where he trained under James Abernethy. There, he gained experience on a number of projects, including the Alexandra dock works at Newport. In 1885, he took the post of assistant to the chief engineer of the South Devon and Cornwall Railway, where he worked on the construction of Plymouth railway station and the widening of the Newton –Torquay railway line. He joined the staff of the Great Western Railway (GWR) in 1887 but set up his own practice shortly after, working under contract to the GWR on a number of projects, as well as a number of harbour works in Plymouth and Torquay.[4]

In 1892, he was appointed Chief Engineer to the Great Western Railway, just after the line had completed its conversion from broad gauge to standard gauge. He was tasked with replacing a number of Isembard Kingdom Brunel's large timber viaducts in Cornwall with new bridges of steel and stone.[4]

Inglis served in the Engineer and Railway Staff Corps, an unpaid volunteer unit of the Volunteer Force which provided technical advice to the British Army. He was appointed a Major in that corps on 24 June 1893, by which time he was also a member of the Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE).[5] He was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel of the Engineer and Railway Staff Corps on 1 April 1908 on the date that it transferred from the disbanded Volunteer Force to the newly raised Territorial Force.[6]

Among his major works were the construction of Fishguard Harbour (establishing a steamboat link with the Midland Great Western Railway and Great Southern and Western Railway at Rosslare Harbour ); the construction of the Badminton railway line in South Wales; and the construction of the Great Western and Great Central Joint Railway (now known as the Chiltern Main Line) between London Marylebone and Birmingham Snow Hill.[4]

Honours and death

Inglis was elected president of the ICE for the November 1908 to November 1910 session.[8] During his time as president he saw the start of construction of their new headquarters at One Great George Street. Inglis ceremoniously laid the foundation stone for the building in 1910 after placing beneath it copies of the institution's Royal Charter and the Telford, Watt and Stephenson medals awarded by the institution.[9] He was knighted by King George V at St James's Palace on 23 February 1911 by which point he was the General Manager of the Great Western Railway.[10] Inglis died on 19 December that year and is buried at Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea Cemetery, Hanwell in London.[3][11]

References

- Institution of Civil Engineers (January 1911), Minutes of the Proceedings, doi:10.1680/imotp.1911.16837, retrieved 31 December 2008

- Masterton, Gordon (2005), ICE Presidential Address (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2009, retrieved 3 December 2008

- "Image of Grave". Find a Grave.

- "James Charles Inglis". Grace's Guide to British Industrial History. Archived from the original on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- "No. 26415". The London Gazette. 23 June 1893. p. 3572.

- "No. 28207". The London Gazette. 22 December 1908. p. 9758.

- Kelly, Alison (2009). "Chalfont Viaduct Buckinghamshire - Historic Building Recording" (PDF). Oxford Archaeology. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 20 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Watson 1988, p. 252.

- Watson 1988, p. 63.

- "No. 28469". The London Gazette. 24 February 1911. p. 1462.

- London Independent Photography Ealing Group, Ealing In A Different Light, archived from the original on 6 October 2011, retrieved 2 January 2009

Bibliography

- Watson, Garth (1988), The Civils, Thomas Telford Ltd, ISBN 0-7277-0392-7

- Watson, Garth (1989), The Smeatonians: The Society of Civil Engineers, London: Thomas Telford Ltd, ISBN 0-7277-1526-7

| Professional and academic associations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by William Matthews |

President of the Institution of Civil Engineers November 1908 – November 1910 |

Succeeded by Alexander Siemens |