Jamaican iguana

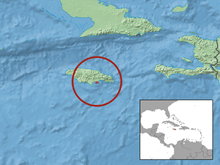

The Jamaican iguana (Cyclura collei) is a large species of lizard in the family Iguanidae. The species is endemic to Jamaica. It is the largest native land animal in Jamaica, and is critically endangered, even considered extinct between 1948 and 1990. Once found throughout Jamaica and on the offshore islets Great Goat Island and Little Goat Island, it is now confined to the forests of the Hellshire Hills.

| Jamaican iguana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Iguania |

| Family: | Iguanidae |

| Genus: | Cyclura |

| Species: | C. collei |

| Binomial name | |

| Cyclura collei Gray, 1845 | |

| |

Etymology

The specific name, collei, is in honor of someone named Colley. John Edward Gray, who originally described this species in 1845, referred to it as "Colley's Iguana". Unfortunately, Gray did not further specify who Colley was.[2]

Anatomy and morphology

The Jamaican iguana is a large heavy-bodied lizard primarily green to salty blue in color with darker olive-green coloration on the shoulders.[3] Three dark broad chevrons extend from the base of the neck to the tail on the animal's back, with dark olive-brown zigzag spots.[3] The dorsal crest scales are somewhat brighter bluish-green than the body.[3] The body surfaces are blotched with a yellowish blotched color breaking up into small groups of spots.[3] Wild individuals, particularly nesting females, often appear deep reddish-brown in color after digging in the coarse ferralic soils of the Hellshire Hills region.[3] Male Jamaican iguanas grow to approximately 428 millimetres (16.9 in) in length whereas females are slightly smaller, growing to 378 millimetres (14.9 in) in length.[1] Males also possess large femoral pores on the undersides of their thighs, which are used to release pheromones.[4] The pores of the female are smaller and they do not have a dorsal crest as high as the male's, making the animal somewhat sexually dimorphic.[4]

Distribution

According to Sir Hans Sloane, a physician and botanist who visited Jamaica in 1688, iguanas were once common throughout Jamaica.[1] The Jamaican iguana declined dramatically during the second half of the 19th century, after the introduction of the Indian mongoose as a form of rat and snake control, until it was believed to exist only on the Goat islands near the Hellshire hills.[1]

The Jamaican iguana was believed to be extinct in 1948.[5] A dead adult specimen was found in 1970. The species was rediscovered in August 1990 when a live adult male iguana was chased into a hollow log by a dog of Edwin Duffus, a hog hunter in the Hellshire Hills. By the time he got there, the dog had injured the animal but that was the iguana that was taken to the Hope Zoo. A remnant population was discovered soon after.[5][6] The Hellshire Hills area is the only area of Jamaica where this iguana is found. It is relegated to two dense populations that consist of scattered individuals.[1][5] They were once prevalent in the island but are now only found in the dry, rocky, limestone forest areas of St. Catherine.[1] Before it was rediscovered in 1990, the iguana was last seen alive on Goat Island off the coast of Jamaica in 1940.[1]

Diet

Like all Cyclura species the Jamaican iguana is primarily herbivorous, consuming leaves, flowers and fruits from over 100 different plant species.[3] This diet is very rarely supplemented with insects and invertebrates such as snails.[3] However, these could simply be eaten incidentally while it consumes the leaves the invertebrates live on.

Conservation

Endangered status

The Jamaican iguana was believed to be extinct dating to 1948. After its rediscovery in 1990, a study showed only that there were only 50 survivors of the "rarest lizard in the world".[5][6] The IUCN lists it as a Critically Endangered Species.[1]

Causes of decline

The single direct cause for the Jamaican iguana's decline can be attributed to the introduction of the small Asian mongoose (Herpestes javanicus) as a form of snake-control.[6][7] The mongoose came to rely upon hatchling iguanas as a prime source of food, prompting the creation of the Headstart facility and a proposed program to eradicate the feral mongoose.[6]

The biggest current threat to the animals' existence is no longer from the spread of the mongoose, but from the charcoal industry.[3][8] Charcoal burners rely on hardwood trees from the Hellshire Hills to make charcoal.[7][8] As this is the primary refuge for the iguanas, the burners have been threatening the research teams who protect the iguanas.[8]

Recovery efforts

A consortium of twelve zoos, also from within the USA donated and constructed a Headstart Facility at Hope Zoo, used for the rearing of eggs and hatchlings brought from the wild.[1][5][8] From within the safety of this environment, they are reared until they are large enough to survive in the wild and predators such as the mongoose are no longer a threat, a process known as "headstarting".[1][6][9] The Headstart facility also carries out health screening prior to the release of specimens.[5][9][10] This health screening has been used to baseline the normal physiologic values of the species, identifying potential future problems due to parasites, diseases, etc. which might threaten the population.[11]

The US captive population doubled in size in August 2006 with the hatching of 22 Jamaican rock iguanas at the Indianapolis Zoo.[8] This was the first successful captive breeding and hatching outside of Jamaica.[8]

References

- Grant, T.D.; Gibson, R.; Wilson, B.S. (1996). "Cyclura collei". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996. Retrieved May 11, 2006.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Cyclura collei, pp. 56-57).

- Vogel, Peter (July 1, 2005), "Jamaican Iguana Cyclura Collei", Iguana Specialist Group, archived from the original on January 14, 2006

- De Vosjoli, Phillipe; David Blair (1992), The Green Iguana Manual, Escondido, California: Advanced Vivarium Systems, ISBN 1-882770-18-8

- Gabriel, Deborah (2005). "Saving the Jamaican Iguana". Reptile Treasures Newsletter. Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved September 9, 2007.

- Wilson, Byron; Alberts, Allison; Grahm, Karen; Hudson, Richard (2004), "Survival and Reproduction of Repatriated Jamaican Iguanas", Iguanas: Biology and Conservation, University of California Press, pp. 220–231, ISBN 978-0-520-23854-1

- Williams-Raynor, Petre (February 11, 2007). "The Jamaican iguana (Cyclura collie)". The Jamaican Observer. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014.

- Hudson, Rick (April 1, 2007), "Big Lizards, Big Problems", Reptiles Magazine, 15 (4): 56

- Alberts, Allison; Lemm, Jeffrey; Grant, Tandora; Jackintell, Lori (2004). "Testing the Utility of Headstarting as a Conservation Strategy for West Indian Iguanas". Iguanas: Biology and Conservation. University of California Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-520-23854-1.

- Iverson, John; Smith, Geoffrey; Pieper, Lynne (2004), "Factors Affecting Long-Term Growth of the Allen Cays Rock Iguana in the Bahamas", Iguanas: Biology and Conservation, University of California Press, p. 200, ISBN 978-0-520-23854-1

- Knapp, Charles R.; Hudson, Richard (2004), "Translocation Strategies as a Conservation Tool for West Indian Iguanas", Iguanas: Biology and Conservation, University of California Press, pp. 199–209, ISBN 978-0-520-23854-1

| Wikispecies has information related to Cyclura collei |

External links

- Profile on Cyclura.com

- The University of the West Indies Department of Life Sciences

- Endangered Jamaican Iguanas Hatched at the Indianapolis Zoo

- Saving the Jamaican Iguana:King of Reptiles(Jamaica)

- Profile on Kingsnake.com

- Jamaican Iguana making a comeback CNN Science

- World Wildlife Fund, ed. (2001). "Jamaican Dry Forests". WildWorld Ecoregion Profile. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 2010-03-08.