Jacques Philippe Bonnaud

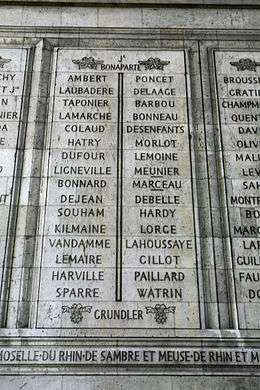

Jacques Philippe Bonnaud or Bonneau (11 September 1757 – 30 March 1797) commanded a French combat division in a number of actions during the French Revolutionary Wars. He enlisted in the French Royal Army as cavalryman in 1776 and was a non-commissioned officer in 1789. He became a captain in the 12th Chasseurs à Cheval Regiment in 1792. The unit fought at Valmy, Jemappes, Aldenhoven, Neerwinden, Raismes, Caesar's Camp and Wattignies, and he was wounded twice. In January 1794 he was promoted to general officer. In April 1794, he reluctantly accepted command of a division that had been cut to pieces at Villers-en-Cauchies and Troisvilles, and this at a time when failed generals often were sent to the guillotine. He led his troops at Courtrai, Tourcoing and in the invasion of the Dutch Republic. He fought in the War in the Vendée the following year, briefly leading the Army of the Coasts of Cherbourg. In the Rhine Campaign of 1796 he led a cavalry division in combat at Amberg, Würzburg and Limburg. He was badly wounded in the latter action and never recovered, dying at Bonn six months later. BONNEAU is one of the names inscribed under the Arc de Triomphe, on Column 6.

Jacques Philippe Bonnaud | |

|---|---|

| Born | 11 September 1757 Bras, Var, France |

| Died | 30 March 1797 (aged 39) Bonn, Germany |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Cavalry |

| Rank | General of Division |

| Commands held | Army of the Coasts of Cherbourg |

| Battles/wars |

|

Early career

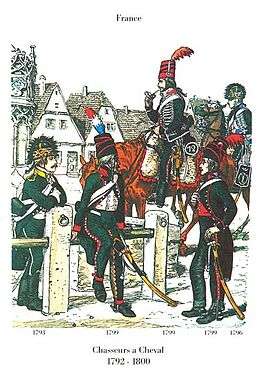

Bonnaud was born on 11 September 1757 in the village of Bras in what later became the Var department of France. On 2 February 1776 he enlisted as a dragoon in the Légion de Dauphiné where he performed the duties of surgeon. While serving in this unit which became the 12th Chasseurs à Cheval Regiment, he was promoted to brigadier on 10 September 1779 and quartermaster (fourrier) on 10 November the same year. He participated in the expedition to Geneva in June 1782. He was elevated in rank to maréchal de logis on 21 September 1784, maréchal de logis chef on 1 July 1788 and adjutant on 1 February 1789.[1] On 18 December 1791 when Emmanuel Grouchy was appointed lieutenant colonel of the 12th Chasseurs à Cheval, its colonel was Jacques-François Menou.[2] Bonnaud became a lieutenant in the regiment on 10 March 1792 and captain on 17 June 1792.[1] Also serving in the regiment, Joachim Murat was a sergeant in July 1792.[3]

Valmy to Wattignies: 1792–1793

On 15 August 1792, the 12th Chasseurs à Cheval Regiment was reviewed at Sedan by Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, who fled to the Austrians a few days later after being accused of treason.[4] On 19 August the Prussian army of Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel attacked Longwy.[5] On 23 August Longwy's 2,600-man French garrison surrendered to 13,731 Austrians with 48 guns and 18,200 Prussians with 88 guns.[6] Verdun's garrison of 4,128 men capitulated to Brunswick on 2 September.[7] In the crisis, the new French army commander Charles François Dumouriez sent Arthur Dillon with an advance guard including the 12th Chasseurs on a false attack toward Stenay. Dumouriez marched the main army south from Sedan, reaching Grandpré on 3 September while Dillon raced ahead to occupy Les Islettes.[8] On 12 September Brunswick broke through Dumouriez's defenses at La Croix-aux-Bois by beating Jean-Pierre François de Chazot's division. While Chazot's troops were in retreat on 15 September, Prussian Hussars appeared. When the 12th Chasseurs attempted to stop them with pistol-fire, the enemy cavalry overran the regiment and sent Chazot's infantry fleeing.[9] At the Battle of Valmy on 20 September, three squadrons of the 12th Chasseurs formed part of Dillon's Advance Guard.[10]

After Valmy, the 12th Chasseurs à Cheval went north as part of the Army of Belgium under Pierre de Ruel, marquis de Beurnonville.[11] Two squadrons of the regiment served in Beurnonville's Advance Guard under Auguste Marie Henri Picot de Dampierre at the Battle of Jemappes on 6 November 1792.[12] The 12th Chasseurs fought at the Battle of Aldenhoven on 1 March 1793[13] from which Henri Christian Michel de Stengel brought off the army pay chest with one squadron from the regiment.[14] At the Battle of Neerwinden on 18 March the 12th Chasseurs may have fought with the right wing.[15] On 1 May in a preliminary action to the Battle of Raismes Bonnaud suffered a saber cut on the cheek and on 6 August he received a sword cut to his left hand at the Battle of Caesar's Camp. By this time his unit was part of the Army of the North.[1] On 15–16 October 1793, the 12th Chasseurs with 511 troopers fought in Jacques Fromentin's division at the Battle of Wattignies.[16]

Abscon to Tourcoing: 1794

On 28 January 1794 Bonnaud was promoted to general of brigade.[17] In the foggy early morning hours of 19 April, he led three mounted regiments against the village of Abscon, wiping out a 70-man Coalition cavalry outpost.[18] As Bonnaud withdrew his 2,400 troopers from their successful raid, they were counterattacked by 630 cavalry under Ludwig von Wurmb. In the inconclusive melee that followed, both sides suffered numerous casualties.[19] On 23 April, 15,000 infantry and 4,500 cavalry from Cambrai and Bouchain moved in four columns to attack Wurmb's force which covered the Siege of Landrecies. The force included 5,000 foot soldiers under Jean Proteau and 1,500 cavalry under Bonnaud.[20] The Battle of Villers-en-Cauchies on 24 April was a Coalition victory by two squadrons each of the Austrian Archduke Leopold Hussars Nr. 17 and the British 15th Light Dragoons. The Austrians lost 20 casualties including 10 missing while the British lost 58 men killed and 17 wounded.[21] After some cavalry maneuvers, the four Coalition squadrons under Rudolf Ritter von Otto and Daniel Mécsery charged Bonneau's horsemen, routing them. They then attacked Proteau's infantry which was drawn up in a large square. After the horsemen broke into the formation, the infantry scattered, leaving behind four pieces of artillery. The Allies claimed to have killed 900 Frenchmen and wounded 400 more. After seeing the fate of Proteau's infantry, the supporting columns retreated to Caesar's Camp.[22]

Following the instructions of Army of the North commander Jean-Charles Pichegru, 30,000 French troops and 80 guns under René-Bernard Chapuy set out from Cambrai late in the night of 25 April to break the Siege of Landrecies. Covered by fog, Chapuy's 18,000-strong center column marched directly on Le Cateau-Cambrésis, the 7,000–8,000-man right column led by Bonnaud advanced through Wambaix and Ligny-en-Cambrésis and the 4,000-strong left column moved toward Solesmes to harass its garrison. After driving the Coalition outposts back to a line of manned redoubts, Chapuy deployed his troops facing southeast toward Troisvilles with his left flank at Audencourt. Chapuy blundered in not posting a flank guard north of Beaumont-en-Cambrésis to guard the Erclin valley. Meanwhile, Bonnaud's right column veered to its left and joined the center column near Bertry.[23] When the fog lifted, Otto and Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany noticed that the French left flank was in air and planned to attack it. The Duke of York sent Otto with six squadrons of Austrian cuirassiers and two small brigades of British heavy cavalry around the unprotected French flank. Spotting the move too late, Chapuy frantically tried to shift cavalry to the left. The right column was able to retreat in haste after Bonnaud intervened with a regiment of carabiniers, keeping two regiments of British light cavalry at bay.[24] The center column, however, was crushed as Otto's horsemen fell on it from the flank and rear. In the Battle of Troisvilles on 26 April the French lost 5,000 killed and wounded, 350 captured including Chapuy, 32 artillery pieces and 44 caissons. The Allies lost 396 cavalrymen while their infantry hardly fired a shot.[25]

Bonnaud received promotion to general of division on 30 April 1794,[17] the same day that Landrecies surrendered to the Coalition.[26] He accepted command of Chapuy's former division after some reluctance.[27] If many officers received rapid promotion at this time, it was also true that many were soon denounced as traitors and executed.[28] Soon after, Pichegru sent the unit from Cambrai to Sainghin-en-Mélantois near Lille where it absorbed Pierre-Jacques Osten's brigade, making the division 23,000-strong. On 10 May Bonnaud's division attacked the Duke of York at Marquain, now a western suburb of Tournai. York turned the French right flank at Camphin-en-Pévèle with three heavy cavalry brigades under David Dundas, Sir Robert Laurie and Richard Vyse. Some of the French cavalry fled but the infantry withdrew without panicking.[29] It was the first time the French infantry formed square with success, driving off British cavalry charges. Finally, artillery firing grapeshot disordered the French squares and the Scots Greys charged, breaking into a square. After this event the cavalry overran two more squares. In the actions at Baisieux and Willems French losses were estimated at 3,000 killed and wounded plus 500 men and 13 guns captured. British losses numbered 245. These combats were part of the larger Battle of Courtrai in which the French emerged victorious.[30]

In the Battle of Tourcoing on 18 May 1794, 82,000 French troops temporarily led by Joseph Souham defeated 74,000 Coalition soldiers under Prince Josias of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld.[31] With the divisions of Souham and Jean Victor Marie Moreau forming a salient at Menen (Menin) and Kortrijk (Courtrai), Karl Mack von Leiberich drew up a plan by which six Coalition columns would encircle them. François Sébastien Charles Joseph de Croix, Count of Clerfayt commanded 19,600 troops of the northern pincer. The southern pincer was formed by columns led by Georg Wilhelm von dem Bussche (4,000), Otto (10,000), the Duke of York (10,750), Franz Joseph, Count Kinsky (11,000) and Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen (18,000), going from north to south. If the French defenders were passive all would have gone well, but execution of Mack's plan demanded rapid movement according to a strict timetable. In the event, only York's and Otto's columns reached their prescribed jumping off points on the evening of 17 May. Clerfayt only crossed the Scheldt River early the next morning while Bussche was beaten and driven off. Kinsky pushed back Bonnaud's troops in his front but fell far behind schedule while Charles suffered an epileptic seizure, halting his progress. Pichegru was absent from his army so the French generals agreed to mount a counterattack under Souham's orders. While Moreau held off Clerfayt, Souham and Bonneau threw their 40,000 troops on the columns of York and Otto. As Souham's division pressed York and Otto from the north, Bonnaud's soldiers struck from the west, capturing ground behind York's column. By the afternoon of the 18th, Otto's men were forced back while York's troops barely cut their way out of the trap with a loss of 32 artillery pieces. After the defeat of the Coalition center, the columns of Clerfayt, Kinsky and Charles were ordered to retreat.[32]

On 22 May 1794 the Coalition defeated the French in the Battle of Tournay.[31] After arriving a day too late for Tourcoing, Pichegru ordered an attack on the Allied position at Tournai. While Souham's division attacked the enemy right flank, Bonnaud pushed against its center, while feinting against the left. After a struggle costly to both sides, the French were compelled to withdraw.[33] On 17 June the French successfully concluded the Siege of Ypres which allowed that part of Flanders to be overrun.[34] By 1 July, the Army of the North seized Bruges and on 10 July, Brussels.[35] There was a lull during which the French reduced the Coalition-held fortresses in northern France. On 1 September Bonnaud's 5th Division counted 9,103 infantry, 1,558 cavalry and 658 gunners manning 34 cannons and five howitzers.[36] On 27 December his division forced the lines of Breda and on 23 January 1795 was the first to enter The Hague.[37] Bonnaud and Jacques MacDonald were credited with the capture of the Dutch fleet at Den Helder on the 23rd, but in fact the feat was accomplished by a relatively junior officer, Louis Joseph Lahure.[38]

Vendée: 1795

Bonnaud's promotion to general of division was not confirmed until 13 June 1795. He was posted to the Army of the Coasts of Cherbourg on 5 July.[37] According to another source, Bonnaud led a reinforcement sent from the Army of the North to fight in the War in the Vendée in December 1794.[39] On 1 September he was sent with 6,000 men from the Cherbourg army to assist Lazare Hoche in defending Nantes and battling the rebel leader François de Charette. He led the 3rd Mobile Column in action against the rebels at Saint-Florent-le-Vieil on 4 October.[37] From 12 November 1795 to 8 January 1796, Bonnaud served as the provisional commander-in-chief of the Army of the Coasts of Cherbourg.[40] He took over from Jean-Baptiste Annibal Aubert du Bayet who became Minister of War.[39] On 26 December 1795, the French Directory ordered the Army of the Coasts of the Ocean to be created by merging the Cherbourg army, Army of the West and Army of the Coasts of Brest. The order was put into effect on 8 January 1796 and Hoche became the new army's commander-in-chief.[41]

Rhine Campaign: 1796

On 3 February 1796, Bonnaud assumed command of the cavalry reserve of Jean-Baptiste Jourdan's Army of Sambre-et-Meuse.[37] The Rhine Campaign of 1796 began on 1 June when the army's left wing under Jean Baptiste Kléber advanced south from Düsseldorf. After Kléber defeated the Austrians in the Battle of Altenkirchen on 4 June, Jourdan sent three infantry divisions plus Bonnaud's cavalry to the east bank of the Rhine at Neuwied.[42] On 15–16 June, Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen with a superior Austrian army beat Jourdan at the Battle of Wetzlar and the French army retreated, Bonnaud and the same three divisions recrossing to the west bank at Neuwied. Jourdan's thrust and withdrawal was intended to allow Jean Victor Marie Moreau's Army of the Rhine and Moselle to get across the Rhine farther south.[43] Moreau's army having established a bridgehead, Jourdan's army advanced again on 28 June and Bonnaud's troopers crossed the Rhine at Bonn on 2 July. After capturing Frankfurt on 16 July, Jourdan left 28,545 soldiers under François Séverin Marceau-Desgraviers to blockade Mainz and Ehrenbreitstein Fortresses and moved east.[44]

By late August the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse faced the Austrian army of Wilhelm von Wartensleben along the Naab River with Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte's division watching its southern flank. Jourdan hoped that Moreau's Army of the Rhine and Moselle would pin down the Austrians in southern Germany, but this did not occur. On 22–23 August Bernadotte's 6,000 troops were attacked by Archduke Charles with 28,000 Austrians. Jourdan sent Bonnaud's cavalry to help, but events moved too fast and Bernadotte made a fighting retreat northwest to Forchheim.[45] Bonnaud never joined Bernadotte and was beset by superior forces as his troopers fell back toward Jourdan's main army. In order to allow Bonnaud to escape, Jourdan stood to fight and was beaten in the Battle of Amberg on 24 August.[46] In his retreat, Jourdan headed for Würzburg with Bonnaud's cavalry in the lead, but the Austrians got there first. On 2 September, two French divisions and the cavalry were in front of Würzburg though a third division did not appear until the evening.[47] Charles defeated the French in the Battle of Würzburg on 3 September. The Austrians sustained 1,500 casualties while the French lost twice as many plus seven guns.[48] The action began at 7:00 am when the left flank French division under Paul Grenier moved forward only to be attacked by a mass of Austrian cavalry. Wartensleben hurled 24 squadrons of cuirassiers at Grenier, but Bonnaud and the divisional French cavalry fought them off. When 12 additional squadrons of Austrian cuirassiers charged, Bonnaud was defeated and forced to shelter behind the French infantry. Jourdan ordered a withdrawal after being hard-pressed by Austrian reinforcements.[49]

By 10 September the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse was spread out in defensive positions behind the Lahn River.[50] Grenier's division held the far left flank at Giessen, François Joseph Lefebvre the left at Wetzlar.[51] Continuing downstream, the French divisions were Jean Étienne Championnet, Bernadotte, François Séverin Marceau-Desgraviers and Jean Castelbert de Castelverd. Meaning to make his main thrust near Limburg an der Lahn to the west, Charles convinced Jourdan to shift his weight to the east.[52] The Battle of Limburg began on 16 September and was a French defeat.[53] That morning Paul Kray attacked Grenier's left flank at Giessen, and though the Austrians were repulsed, Jourdan sent Bonnaud's cavalry, some infantry and artillery to help. Later, Kray attacked again, forcing back Grenier's right wing brigade. Using a ravine for cover, Bonnaud led two cavalry squadrons to a position from which he charged the Austrian flank. Grenier's infantry rallied and drove back Kray's troops, but during his successful charge Bonnaud's thigh was broken by a shot.[52] He never recovered from his wound, dying at Bonn on 30 March 1797. Historian Ramsay Weston Phipps believed that Bonneau was Jourdan's "most satisfactory" cavalry commander.[54] His surname is inscribed under the Arc de Triomphe.[55]

Notes

- Charavay 1893, p. 39.

- Phipps 2011a, p. 103.

- Phipps 2011a, p. 63.

- Phipps 2011a, pp. 106–107.

- Phipps 2011a, p. 111.

- Smith 1998, p. 24.

- Smith 1998, p. 25.

- Phipps 2011a, p. 119.

- Phipps 2011a, pp. 120–121.

- Smith 1998, p. 26.

- Phipps 2011a, p. 138.

- Smith 1998, p. 30.

- Smith 1998, p. 42.

- Phipps 2011a, p. 154.

- Phipps 2011a, pp. 155–156.

- Dupuis 1909, p. 100.

- Broughton 2006.

- Coutanceau & LaJonquière 1907, p. 290.

- Coutanceau & LaJonquière 1907, p. 292.

- Coutanceau & LaJonquière 1907, p. 370.

- Smith 1998, pp. 74–75.

- Coutanceau & LaJonquière 1907, pp. 377–379.

- Coutanceau & LaJonquière 1907, pp. 412–414.

- Coutanceau & LaJonquière 1907, pp. 415–420.

- Coutanceau & LaJonquière 1907, pp. 421–425.

- Smith 1998, p. 76.

- Phipps 2011a, p. 290.

- Phipps 2011a, pp. 26–27.

- Phipps 2011a, pp. 294–295.

- Smith 1998, p. 78.

- Smith 1998, pp. 79–80.

- Phipps 2011a, pp. 296–306.

- Phipps 2011a, pp. 309–311.

- Smith 1998, p. 85.

- Phipps 2011a, p. 318.

- Phipps 2011a, p. 324.

- Charavay 1893, p. 40.

- Phipps 2011a, p. 330.

- Phipps 2011c, p. 47.

- Clerget 1905, p. 51.

- Clerget 1905, p. 56.

- Phipps 2011b, pp. 279–281.

- Phipps 2011b, pp. 282–285.

- Phipps 2011b, pp. 295–297.

- Phipps 2011b, pp. 337–338.

- Phipps 2011b, pp. 340–341.

- Phipps 2011b, p. 350.

- Smith 1998, pp. 121–122.

- Phipps 2011b, pp. 351–352.

- Phipps 2011b, pp. 353.

- Phipps 2011b, p. 359.

- Rickard 2009.

- Smith 1998, p. 124.

- Phipps 2011b, p. 360.

- See photo.

References

- Broughton, Tony (2006). "Generals Who Served in the French Army during the Period 1791 to 1815: Bicquilley to Butraud". The Napoleon Series. Retrieved 4 August 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Charavay, Jacques (1893). "Les Généraux Morts Pour La Patrie 1792-1871" (in French). Paris: Charavay. Retrieved 31 July 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clerget, Charles (1905). "Tableaux des Armées Françaises pendant les Guerres de la Révolution" (in French). Paris: Librarie Militaire R. Chapelot et Cie. Retrieved 31 July 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coutanceau, Michel H. M.; LaJonquière, Clement (1907). "La campagne de 1794 à l'armee du Nord" (in French). Paris: R. Chapelot et cie.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dupuis, Victor (1909). "La Campagne de 1793 à l'Armée du Nord et des Ardennes d'Hondtschoote à Wattignies" (in French). Paris: Librairie Militaire R. Chapelot et Cie. Retrieved 4 August 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Phipps, Ramsay Weston (2011a). The Armies of the First French Republic: Volume I The Armée du Nord. 1. USA: Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-908692-24-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Phipps, Ramsay Weston (2011b). The Armies of the First French Republic: Volume II The Armées du Moselle, du Rhin, de Sambre-et-Meuse, de Rhin-et-Moselle. 2. USA: Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-908692-25-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Phipps, Ramsay Weston (2011c). The Armies of the First French Republic: Volume III The Armies in the West 1793 to 1797 And, The Armies In The South 1793 to March 1796. 3. USA: Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-908692-26-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rickard, J. (2009). "Combat of Giessen, 16 September 1796". historyofwar.org.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Jean-Baptiste Annibal Aubert du Bayet |

Provisional Commander-in-chief of the Army of the Coasts of Cherbourg 12 November 1795–8 January 1796 |

Succeeded by Merged into Army of the Coasts of the Ocean |