Jacob the Liar (1975 film)

Jacob the Liar (German: Jakob der Lügner) is a 1975 East German-Czechoslovakian Holocaust film directed by Frank Beyer, and based on the novel of the same name by Jurek Becker. It starred Vlastimil Brodský in the title role.

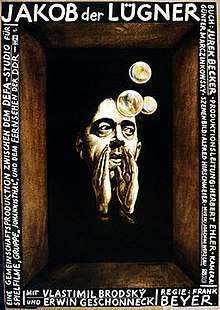

| Jacob the Liar | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Frank Beyer |

| Produced by | Herbert Ehler |

| Written by | Jurek Becker Frank Beyer |

| Starring | Vlastimil Brodský |

| Music by | Joachim Werzlau |

| Cinematography | Günter Marczinkowsky |

| Edited by | Rita Hiller |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Progress Film |

Release date |

|

Running time | 100 minutes |

| Country | German Democratic Republic Czechoslovakia |

| Language | German |

| Budget | 2,411,600 East German Mark |

Work on the picture began in 1965, but production was halted in summer 1966. Becker, who had originally planned Jacob the Liar as a screenplay, decided to make it a novel instead. In 1972, after the book garnered considerable success, work on the picture resumed.

Plot

In a Jewish ghetto in German-occupied Poland, a man named Jakob is caught on the streets after curfew. He is told to report to a German military office where he finds the officer in charge passed out drunk. The radio is running and Jakob hears a broadcast about the advances of the Soviet Army. Eventually, Jakob sneaks out and goes home. Later he tells his friends that the Russians are not very far away. As no one believes he went to the Nazi office and came out alive, Jakob makes up a lie, claiming he owns a radio - a crime punishable by death. This puts Jakob in a difficult position since he is constantly asked for further news. He then starts encouraging his friends with false reports about the advance of the Red Army towards their ghetto. The residents, who are desperate and starved, find new hope in Jakob's stories. Even when he eventually confesses to his friend that only the first report was true and all the rest is made up, his friend points out that his stories give people hope and a will a to live. The film ends with the deportation of Jakob and the others to the extermination camps.

Cast

- Vlastimil Brodský - Jakob Heym (voiced by Norbert Christian)

- Erwin Geschonneck - Kowalski

- Henry Hübchen - Mischa

- Blanche Kommerell - Rosa Frankfurter

- Manuela Simon - Lina

- Armin Mueller-Stahl - Roman Schtamm

- Peter Sturm - Leonard Schmidt

- Dezső Garas - Mr. Frankfurter (voiced by Wolfgang Dehler)

- Margit Bara - Josefa Litwin (voiced by Gerda-Luise Thiele)

- Reimar J. Baur - - Herschel Schtamm

- Zsuzsa Gordon - Mrs. Frankfurter (voiced by Ruth Kommerell)

- Friedrich Richter - Dr. Kirschbaum

- Hermann Beyer - Duty officer

- Klaus Brasch - Josef Neidorf

- Jürgen Hilbrecht - Schwoch

Production

First attempt

While still attending university, Jurek Becker heard from his father a story about a man from the Łódź Ghetto who owned a radio and passed news from the outside world, risking execution by the Germans.[1] As Becker became a screenwriter in the early 1960s, he decided to compose a film script based on the story. On 10 January 1963, he submitted a 32 pages long treatment to the DEFA studio, the state-owned cinema monopoly of the German Democratic Republic. The studio approved of the work and authorized to further develop it.[2] Becker was paid 2,000 East German Mark.[3] On 17 February 1965, he handed a 111 pages long scenario over to the studio, and a full script of 185 pages was submitted by him on 15 December.[2]

During 1965, as work on the script progressed, Frank Beyer requested to direct the future film and received the role. On 9 February 1966, the director-general of DEFA, Franz Bruk, submitted the script to the chairman of the Ministry Of Culture's Film Department, Wilfried Maaß, and requested permission to commence production. Maaß replied the scenario should be historically accurate: in Becker's work, the Red Army freed the ghetto just before the residents were deported, although Jakob died on the barbed wire fence. The chairman pointed out no Jewish ghettos were rescued in such a manner at the war, as the Germans managed to evacuate them all. However, on 22 February he granted permission to begin work on the picture.[4] Beyer decided to cast Czechoslovak actor Vlastimil Brodský for the role of Jakob, and DEFA began negotiations with the Barrandov Studios.[5]

Cancellation

The producers soon encountered difficulties. In the end of 1965, from the 16th to the 18th of December, the Socialist Unity Party of Germany assembled for its XI Plenum. During the convention, the cinema industry was severely criticized and blamed for taking artistic liberties incongruous with Marxist ideology. In the following year, some twelve recently produced pictures were banned: the most prominent of those were Kurt Maetzig's The Rabbit Is Me and Beyer's Trace of Stones. The latter had its premiere in summer 1966, but was soon removed from circulation. Consequently, the director was reprimanded by the Studio directorate and blacklisted. He was forbidden to work in cinema, and was relegated to work in theater, and later to Deutscher Fernsehfunk, the East German state television.[6] Subsequently, the production of Jacob the Liar ceased on 27 July 1966.[7]

Becker's biographer Beate Müller wrote that while the implications of the Plenum played a part in this, "it would be misleading to lay all responsibility there": neither Becker nor the film were mentioned by the Party, and DEFA might have simply found another director.[8] Beyer wrote the film was deemed sound on the political level, adding the censure never tried to interfere with Jacob the Liar.[9] There were other reasons: Beyer intended to hold principal photography in Poland, mainly in the former Kraków Ghetto, and requested the authorities of the People's Republic of Poland for permission; He also planned to have the Poles help finance the picture. The Polish United Film Production Groups responded negatively.[10] Beyer believed the sensitivity of the subject of the Holocaust in Poland stood behind the rejection.[11] More important, the banning of many of the pictures made in 1965 and the abortion of other future projects that were under way and feared to be non-conformist had run DEFA into a financial crisis. All future revenues were now dependent on the pictures that were not affected by the Plenum, and only a meager budget remained for new undertakings.[12]

Completion

The rejection of the film motivated Becker to turn his screenplay into a novel.[13] Jacob the Liar was first published in 1969, and became both a commercial and a critical success, winning several literary prizes, also in West Germany and abroad.[14] The acclaim it received motivated the West German ZDF television network to approach the author and request the rights to adapt it. Becker, who was now a famous and influential author, went to Beyer instead and suggested they resume work on the unfinished picture from 1966. The director proposed to make it a co-production of DEFA and DFF.[15] The picture - which was always positively viewed by the establishment - was never banned, and the studio maintained an interest to film the script throughout the years passed.[16] On 16 March 1972, a contract was signed between Becker and the studios. He handed over a 105-page scenario on 22 June 1972,[2] which was approved on 11 August. A final script, with 152 pages, was authorized by DEFA on 7 January 1974.[17]

The film was financed by both companies, with each paying half of the 2.4 million East German Mark budget, which was rather average for DEFA pictures made in the 1970s.[18] Beyer completely rejected filming in Poland this time. He chose to conduct outdoor photography in the Czechoslovak city of Most, the historical center of which was undergoing demolition; he believed the ruins would best serve as the site of the ghetto.[19]

West German actor Heinz Rühmann, who was offered to depict Jakob by ZDF while its directors believed they would receive the rights, insisted on portraying him even in the DEFA production. Erich Honecker had personally decided to reject him, in what Katharina Rauschenberger and Ronny Loewy called "probably his only productive decision in the field of art... Happily, the film was spared from Rühmann". Brodský was invited again to portray the title role.[20] Jerzy Zelnik was supposed to star as Mischa, but the Polish state-owned film production monopoly Film Polski, which demanded more details about the film from the East Germans, undermined the attempt. Eventually, Henry Hübchen received the role.[17] The cast also featured two concentration camp survivors: Erwin Geschonneck and Peter Sturm.

Principal photography commenced on 12 February 1974, and ended on 22 May. Editing began on 4 June. The studio accepted the picture in October, requiring only minor changes. The final, edited version was completed on 3 December. The producers remained well within their budget confines, and the total cost of Jacob the Liar was summed to 2,411,600 East German Mark.[18]

Reception

Distribution

Jacob the Liar was never expected to be a commercial success: DEFA officials who held a preliminary audience survey in 1974 estimated on 28 May that no more than 300,000 people would view it. Müller believed that for this reason, although its premiere in cinemas was to be held in early 1975, both DEFA and the Ministry of Culture did not object when the DFF directorate requested to broadcast it first on television, claiming they lacked an "emotional high point" for the 1974 Christmas television schedule. On Sunday, 22 December 1974, a black-and-white version was screened by DFF 1, in one of the leading prime time slots of its annual schedule. It was seen by "millions of viewers".[21]

When it was eventually distributed to cinemas in April 1975, its attendance figures were further damaged by the earlier broadcast on television.[22] It was released in only seventeen copies, and sold merely 89,279 tickets within the first thirteen weeks.[23] The number rose to only 164,253 after a year, to 171,688 by the end of 1976 and to 232,000 until 1994.[22]

In spite of this, Jacob the Liar became an international success: it was exported to twenty-five foreign states, a rare achievement for an East German film, especially since only five of those were inside the Eastern Bloc: Hungary, Cuba, Bulgaria, Romania and Czechoslovakia. Most DEFA pictures of the 1970s were allowed in no more than one non-communist state, if any at all, while Beyer's film was bought by distributors in West Germany, Austria, Greece, Italy, the United States, Iran, Japan, Angola, and Israel, among others. In that respect, "Jacob the Liar was certainly no flop."[24]

Awards

On 1 October 1975, Becker, Beyer, Brodský, actor Erwin Geschonneck, dramatist Gerd Gericke and cinematographer Günter Marczinkowsky received the National Prize of East Germany 2nd class in collective for their work on the picture.[25]

The film was turned down by the organizers of the IX Moscow International Film Festival, held in July 1975, due to its subject, which was deemed "outdated".[26] Becker's biographer Thomas Jung claimed the reason was "the taboo theme of antisemitism in Eastern Europe".[27]

Jacob the Liar was the first ever East German film that was entered into the Berlin International Film Festival in West Berlin:[28] in the XXV Berlinale, Vlastimil Brodský won the Silver Bear for Best Actor.[29] It was also nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film at the 49th Academy Awards,[30] the only East German picture ever to be selected.[31][32][33]

Critical response

Hans-Christoph Blumenberg of Die Zeit commented: "Gently, softly, without cheap pathos and sentimentality, Beyer tells a story about people in the middle of horror... The remarkable quality of this quiet film is achieved not least due to superb acting by the cast."[34]

The New York Times reviewer Abraham H. Weiler wrote Jacob the Liar "is surprisingly devoid of anything resembling Communist propaganda... Brodský is forceful, funny and poignant". He added it "illustrates Mark Twain's observation that 'courage is resistance to fear, mastery of fear, and not the absence of fear'".[35]

Analysis

Martina Thiele noted that Jacob the Liar "is one of the few DEFA pictures that may be called 'Holocaust films'". While the topic was not infrequent in East German cinema, it was usually portrayed in a manner conforming to the official view of history: the victims were portrayed as completely passive, while the emphasis was laid on the communist struggle against the Nazis. In Beyer's film, a Jew was first seen to offer resistance.[36]

Paul Cooke and Marc Silberman present a similar interpretation: it was "the first film to link Jews with the theme of resistance, albeit a peculiarly unheroic type". Jakob was still a representation of the stereotypical effeminate Jew, reminding of Professor Mamlock, and although he "exhibits a certain degree of agency", he still does so out of almost maternal, nurturing instincts.[37]

Daniela Berghahn wrote "the innovative aspects" of the film "consist of its new approach... The use of comedy... It pays no tribute to history's victors, only to its victim... By turning the negatives into positives, Beyer conveys a story of hope... And makes the impact of Jakob's lie on ghetto life tangible".[38]

Remake

An American remake starring Robin Williams was released in 1999.

See also

- List of submissions to the 49th Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of German submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

References

- "Jacob the Liar". University of Massachusetts Amherst. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- Müller. p. 81.

- Müller. p. 75.

- Müller. p. 82.

- Müller. p. 83.

- Müller. pp. 84-86.

- Gilman. p. 66.

- Müller. p. 88.

- Beyer. p. 187.

- Müller. pp. 88-89.

- Beyer. p. 184.

- Müller. pp. 89-90.

- Müller. pp. 92-94.

- Figge, Ward. p. 91.

- Müller. p. 122

- Müller. p. 90.

- Müller. p. 123.

- Müller. p. 126.

- Beyer. p. 191.

- Loewy, Rauschenberger. pp. 198-199.

- Müller. p. 127.

- Müller. p. 129.

- Berghahn. p. 92.

- Müller. pp. 129-130.

- "DEFA-Chronik für das Jahr 1975". defa.de. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- Liehm. p. 361.

- Jung. p. 128.

- "25th Berlin International Film Festival June 27 - July 8, 1975". berlinale.de. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- "Berlinale 1975: Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- "The 49th Academy Awards (1977) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- Brockmann. p. 231.

- Agence France-Presse (3 October 2006). "Frank Beyer, 74, East German Who Directed 'Jacob the Liar,' Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- Bergan, Ronald (10 October 2006). "Frank Beyer, Film Director Whose Work was Blighted by East German Censorship". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- Blumenberg, Hans-Christoph (5 March 1976). "Filmtips". Die Zeit. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- Weiler, Abraham H. (25 April 1977). "Jacob the Liar, a Film About the Polish Ghetto". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- Thiele. pp. 100-101.

- Cooke, Silberman. pp. 141-142.

- Berghahn. pp. 90-92.

Bibliography

- Müller, Beate (2006). Stasi - Zensur - Machtdiskurse: Publikationsgeschichten Und Materialien Zu Jurek Beckers Werk. Max Niemeyer. ISBN 9783484351103.

- Beyer, Frank (2001). Wenn der Wind sich Dreht. Econ. ISBN 9783548602189.

- Liehm, Miera; Antonin J. (1977). The Most Important Art: Soviet and Eastern European Film After 1945. University of California Press. ISBN 0520041283.

- Gilman, Sander L. (2003). Jurek Becker: A Life in Five Worlds. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226293936.

- Figge Susan G.; Ward, Jenifer K. (2010). Reworking the German Past: Adaptations in Film, the Arts, and Popular Culture. Camden House. ISBN 9781571134448.

- Loewy, Ronny; Rauschenberger, Katharina (2011). "Der Letzte der Ungerechten": Der Judenälteste Benjamin Murmelstein in Filmen 1942-1975. Campus. ISBN 9783593394916.

- Berghahn, Daniela (2005). Hollywood Behind the Wall: The Cinema of East Germany. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719061721.

- Jung, Thomas K. (1998). Widerstandskaempfer oder Schriftsteller sein... P. Lang. ISBN 9783631338605.

- Brockmann, Stephen. A Critical History of German Film. ISBN 9781571134684.

- Thiele, Martina (2001). Publizistische Kontroversen über den Holocaust im Film. Lit. ISBN 3825858073.

- Cooke, Paul; Silberman, Marc (2010). Screening War: Perspectives on German Suffering. Camden House. ISBN 9781571134370.