J. Percy Priest Dam

J. Percy Priest Dam is a dam in north central Tennessee at river mile 6.8 of the Stones River, a tributary of the Cumberland. It is located about ten miles (16 km) east of downtown Nashville. The reservoir behind the dam is Percy Priest Lake. It is one of four major flood control reservoirs for the Cumberland; the others being Wolf Creek Dam, Dale Hollow Dam, and Center Hill Dam.[1]

.jpg)

The Flood Control Act of 1946 commissioned the construction of a project under the name Stewarts Ferry Reservoir. Public Law 85-496, approved July 2, 1958, changed the name to J. Percy Priest in honor of the late Congressman from Tennessee.[2] Construction began June 2, 1963 and the dam was completed in 1968. The dam was built under U.S. Army Corps of Engineers supervision.

In 1979 the dam was attacked with dynamite, with hopes of providing cover for a crime spree by collapsing the dam and causing a massive flood in the area. The conspirators only succeeded in causing $10,000 worth of damage to four iron doors at the dam's base. Two suspects were later convicted and sentenced to substantial prison terms. US Attorney Hal Harding later claimed, in response to the fact a whole case of dynamite was used to little effect, that "it would be almost impossible to blow up a dam even with a truckload of dynamite".[3]

Rising 130 feet (40 m) above the streambed, the combination earth and concrete-gravity dam is 2,716 feet (828 m) long with a hydroelectric power plant generating 28 MW of electrical power which is fed into the grid of the Tennessee Valley Authority. The TVA co-ordinates operation of the Corps of Engineers dams in the Cumberland River Valley. The dam has contributed significantly in reducing the frequency and severity of flooding in the Cumberland Valley. In addition to the far-reaching effects of flood control, the project contributes to the available electric power supply of the area.

The dam is easily visible from Interstate 40 where it crosses the Stones River.

The completion of the dam in 1967 resulted in the destruction of the last known population of the freshwater mussel Epioblasma lenior, which is now extinct. [4]

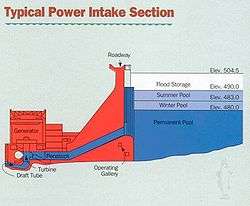

Reservoir elevations (behind the dam)

(elevations are in feet above mean sea level)

- 504.50 ft The dam can hold flood waters up to this level

- 494.50 ft Elm Hill Marina begins to flood by surpassing the individual walkways to the boat docks

- 490.00 ft Summer Pool (April to October)

- 483.00 ft Winter Pool (November to March)

- 480.00 ft Permanent Pool

Tailwater elevation (below the dam)

Current elevations and hourly discharge information can be found at: https://www.tva.gov/Environment/Lake-Levels/J-Percy-Priest

Hourly discharge

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) reports all discharge information online viewable to the public. Current elevations and hourly discharge information can be found at: https://www.tva.gov/Environment/Lake-Levels/J-Percy-Priest

It has been found that if J Percy Priest dam is discharging up to 9,000 cu ft/s (250 m3/s) it takes about 28 hours for the reservoir elevation to recede 1-foot (0.30 m).

References

- "Corps of Engineers says releasing water from Tenn. dam prevented more damage to Nashville". May 11, 2010. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- Dates in Nashville District History Archived 2012-05-31 at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Nashville District website, accessed August 11, 2009

- Reading Eagle, January 7, 1979

- Parmalee, P. W., & Bogan, A. E. (1998). Freshwater mussels of Tennessee.

External links

- Priest Dam project changed lives of many – The Tennessean

- View Weather & Maps - Unearthed Outdoors

- www.tva.gov/lakes/jph_o.htm

![]()