Itzgründisch dialect

Itzgründisch is a Main Franconian dialect, which is spoken in the eponymous Itz Valley (German: Itzgrund) and its tributaries of Grümpen, Effelder, Röthen/Röden, Lauter, Füllbach and Rodach, the valleys of the Neubrunn, Biber and the upper Werra and in the valley of Steinach. In the small language area, which extends from the Itzgrund in Upper Franconia to the southern side of the Thuringian Highlands, “Fränkische” (specifically East Franconian) still exists in the original form. Because of the remoteness of the area, this isolated by the end of the 19th century and later during the division of Germany, this language has kept many linguistic features to this day. Scientific study of the Itzgründisch dialect was made for the first time, in the middle of the 19th century, by the linguist August Schleicher.

| Itzgründisch | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Germany |

| Region | Northern Bavaria, Southern Thuringia |

Native speakers | 230,000 (2010) |

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

Geographical Distribution

The zone of the Itzgründisch dialect includes south of the Rennsteig ridge in the district of Sonneberg, the eastern part of the district of Hildburghausen, the city and district of Coburg (the “Coburger Land”) and the northwestern part of the district of Lichtenfels.

In the west side of the dialect zone, the “Südhennebergische Staffelung” [South Henneberger Gradation, a linguistic term], which runs through the district of Hildburghausen, separates Itzgründisch from Hennebergisch. It extends south of the city of Hildburghausen and continues along the zone's borders to Grabfeldisch (East Franconian) or further south to Lower Franconian, which is also spoken in Seßlach in the western part of the district of Coburg. South of the district of Coburg, Itzgründisch is mixed with the dialect of Bamberg. East of the Sonneberger (except Heinersdorf, which is already in the zone of the Upper Franconian dialect) and Coburger lands and east of Michelau in the district of Lichtenfels, the Itzgründisch-speaking area is bordered by its Upper Franconian counterpart. Upper Franconian lies beyond the “Bamberger Schranke” [Bamberg Barrier, another linguistic term] so it does not belong to the Main Franconian dialects.

Directly in the course of the Rennsteig over the crest of the Thuringian Highlands, there exists a narrow transition zone to the Thuringian dialect, which consists the more modern dialects, largely influenced by East Franconian, of the places around Sachsenbrunn and Lauscha, which use the Itzgründisch vocabulary.

The zone of the Itzgründisch dialect area was originally the territories of the historic rulers, the Pflege Coburg and the Benedictine Banz Abbey.

Speakers

On 31 December 2010, in the dialect zone of Itzgründisch, 41,076 speakers were living in the town of Coburg while 84,129 were residing in the district of Coburg, with 40,745 more in the district of Hildburghausen; 22,791 in the district of Lichtenfels; and (minus the estimated number of non-Itzgründisch-speakers) about 50,000 inhabitants in the district of Sonneberg. In the town of Lichtenfels, which lies on the south bank of the Main River, where its dialect has historically been mixed with the dialects of Bamberg and the Itz Valley, 20,555 residents were counted. While respective variants of Itzgründisch are spoken in the rural villages throughout the area, the proportion of non-Itzgründisch-speaking residents is much greater in the cities. A conservative estimate puts the number of the native speakers of Itzgründisch at about 225,000 speakers.

The local dialects dominate in the transitional zone at the Rennsteig, where they are spoken by most of the approximately 13,000 inhabitants in everyday life, except in the town of Neuhaus am Rennweg.

Features

The grammar of Itzgründisch basically follows the rules of the East Franconian dialect. The uniqueness of Itzgründisch compared with other German dialects is in increasingly obsolete forms and diphthongs of Middle High German that are common in everyday speech.

- Around Sonneberg and Neustadt bei Coburg the diphthongs iä, ue and üä are used, for example: nicht [not] = “niä”, Beet [bed] = “Biäd”, Ofen [oven] = “Uefm”, Vögel [birds] = “Vüächl”. The pronunciation of the double consonant, -rg is changed to -ch if it follows the vowel, for example: Sonneberg = “Sumbarch”, ärgern [to anger] = “archern” and morgen [morning] = “morchng”. Other diphthongs exist in the following words, for example: Brot [bread] = “Bruad”, Hosen [pants] = “Huasn”, Hasen [hares] = “Housn”, heißen [to be called] = “heaßn” or schön [beautiful] = “schööä”.

- Sentences are often formed with auxiliary verbs such as mögen [to like], wollen [to want or wish], machen [to make], tun [to do] or können [to be able] and with the past participle. (Das Kind schreit. [The child cries.] = “Des Kindla dud schrein.” or “Des Kindla ka fei g´schrei.”)

- The past participle is almost always used to construct the sentence with the auxiliary verbs sein [to be] or haben [to have]. Example: Da gingen wir hinein/Da sind wir hineingegangen. [As we walked inside / As we went inside] = “Dou sä´me neig´anga.” In the north side of the dialect zone, however, the differences in the changes of grammatical tenses and verbs are more noticeable. They are known in the Thuringian places such as Judenbach or Bockstadt as the past tenses of certain verbs, which are already expressed in the North German dialects as the preterites, which are virtually unknown in East Franconian. In Sachsenbrunn and Lauscha, which lay near the Rennsteig outside the Itzgründisch dialect zone, more than three-quarters of the verbs are already used in the past tense.

- Wherever the speech is uninhibited in the dialect, sentences are constructed with double negatives, for example: “Wenn da kää Gald niä host, kaas da de fei nex gekeaf.” (Wenn du kein Geld (nicht) hast, kannst du dir nichts kaufen.) [If you don't have no money, you can't buy nothing.] or “Doumit kaast da kä Eä niä eigelech.” (Damit kannst du kein Ei (nicht) einlegen.) [With that, you can't load no eggs.]

- As they are in Main Franconian, the modal particle fei and the diminutives -lein and -la (locally, also -le) are used very much and often.

(Note: Because Itzgründisch does not have the standard written form, the text is different in approximately "normal" letters with each different author. For this reason, the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is waived for the exact wording of the Itzgründisch words and phrases in this article.

Numbers in the Sonneberger Dialect

|

|

|

But the numbers are different in time (in the mornings as well as the afternoons), as follows:

|

|

Example: Es ist um Ein Uhr. (It is one o’clock) = Es is in Easa. (The “i” is “swallowed” so much that it is only partially audible.)

Weekdays in the Sonneberger Dialect

|

|

|

Variations Between Itzgründisch and Upper Franconian

Itzgründisch has a diversity of local variations. For example, while a girl would be called Mädchen in proper German, she would be called Mädle in Haselbach, "Mädla" in the neighboring Steinach and "Meadla" in Sonneberg. The differences are even more pronounced in Upper Franconian, which is also spoken in Heinersdorf in the district of Sonneberg.

| German | Itzgründisch | Upper Franconia | English |

| Mädchen | Meadla (Mädla) | Madla | maiden |

| Heinersdorf | Heaneschdaff | Haaneschdaff | Heinersdorf |

| zwei Zwetschgen | zweji Gwadschge | zwa Zwetschgä | two plums |

| Sperling | Schperk | Schbootz | sparrow |

| angekommen | akumma | akumma | arrived |

| hinüber geholt | nübe ghuald | nübe ghold | brought over |

| hinunter | nou, nunde | nunde | down |

| Gras | Grous | Grous | grass |

| Hase, Hasen | Hous, Housn | Hos, Hosn (Has, Hasn) | hare |

| Nase, Nasen | Nous, Nousn | Nos, Nosn (Nas, Nasn) | nose |

| Hose, Hosen | Huas, Huasn | Hos, Hosn | trousers |

| rot, Not, Brot | ruad, Nuad, Bruad | rod, Nod, Brod | red, need, bread |

| eins; heiß | eas (ääs); heas (hääs) | ans (ääs); haas (hääs) | one, hot |

| nicht | niä (niät, net) | net (niät) | not |

| Salzstreuer (auf dem Tisch) | Soulznapfla (Salznäpfla) | Salzbüchsle (Salznäpfle) | Salt shaker |

| Tasse | Kabbla | Dässla | cup |

| Kloß, Klöße | Klueß, Klüeß | Kloß, Klöß/Kließ | dumpling, dumplings |

| daheim | deheam (dehämm), hämma | daham | at home |

| Gräten | Graadn | Gräidn | fishbones |

| Ich kann dir helfen. | Ich kaa de ghalf (gehelf). | Ich kaa de (dich) helf. | I can help you. |

| Geh (komm) doch mal her. | Gih amo haa. | Geh amol hää. | Just go (come) over here. |

| ein breites Brett | a breads Braad | a braads Breet | a wide board |

Words Unique to Itzgründisch

A selection of some terms:

- Ardöpfl, Arpfl = Erdapfel, Kartoffel (potato)

- Glikeleskaas = Quark (Quark)

- Stoal = Stall (stable)

- Stoudl = Scheune (barn)

- Sulln = Sohle, Schlampe (sole, bitch)

- Zahmet = Kartoffelbrei (mashed potatoes)

- Zähbei = Zahnschmerzen (toothache)

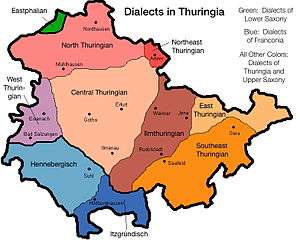

Linguistic Map

- (de) Thüringer Dialektatlas, Heft 27, Deutsche Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin [Atlas of the Thuringian Dialects, Issue 27, German Academy of Sciences in Berlin], Berlin, Akademie-Verlag-Berlin, 1969

The Dialect Atlas shows the distribution of parts of speech and the corresponding sound shifts.

Literature

- (de) August Schleicher: Volkstümliches aus Sonneberg im Meininger Oberlande – Lautlehre der Sonneberger Mundart [Popular Speech from Sonneberg in the Meiningen Highlands – Phonology of the Sonneberger Dialect]. Weimar, Böhlau, 1858.

- (de) Otto Felsberg: Die Koburger Mundart. Mitteilungen der Geographischen Gesellschaft für Thüringen: Band 6 [The Coburger Dialect. Bulletins of the Geographical Society of Thuringia: Volume 6], Jena, 1888, p. 127–160.

- (de) Karl Ehrlicher: Zur Syntax der Sonneberger Mundart. Gebrauch der Interjection, des Substantivs und des Adjectivs [The Syntax of the Sonneberger Dialect: Use of the Interjections, the Nouns and the Adjectives]. Inaugural-Dissertation an der Hohen Philosophischen Fakultät der Universität Leipzig [Inaugural Dissertation at the Faculty of High Philosophy of the University of Leipzig], 1906

- (de) Alfred Förster: Phonetik und Vokalismus der ostfränkischen Mundart der Stad Neustadt (Sachs-en-Coburg) [Phonetics and Vocals of the East Franconian Dialect of the City of Neustadt (Saxe-Coburg)]. Jena 1912 and Borna-Leipzig, 1913 (Partial printing).

- (de) Wilhelm Niederlöhner: Untersuchungen zur Sprachgeographie des Coburger Landes auf Grund des Vokalismus [Studies of the Linguistic Geography of the Coburger Land on the Basis of Vocals]. Erlangen, 1937.

- (de) Eduard Hermann: Die Coburger Mundart [The Coburger Dialect]. In: Adolf Siegel (ed.): Coburger Heimatkunde und Heimatgeschichte. Teil 2, Heft 20 [Coburger Local Genealogical and Historical Society, Part 2, Issue 20]. Coburg, 1957.

- (de) Heinz Sperschneider: Studien zur Syntax der Mundarten im östlichen Thüringer Wald [Studies of the Syntax of the Dialects in Eastern Thuringian Forest]. Deutsche Dialektgeographie 54 [German Dialect Geography], Marburg, 1959.

- (de) Emil Luthardt: Mundart und Volkstümliches aus Steinach, Thüringerwald, und dialektgeographische Untersuchungen im Landkreis Sonneberg, im Amtsbezirk Eisfeld, Landkreis Hildburghausen und in Scheibe, im Amtsgerichtsbezirk Oberweißbach, Landkreis Rudolstadt [Dialects and Slang from Steinach, Thuringian Forest, and Linguistic-Mapping Investigation in the District of Sonneberg, in the Subdistrict of Eisfeld, District of Hildburghausen and in Scheibe, in the subdistrict of Oberweißbach, District of Rudolstadt]. Dissertation. Hamburg, 1963.

- (de) Harry Karl: Das Heinersdorfer Idiotikon [The Complete Dictionary of the Heinersdorfer Dialect]. Kronach, 1988.

- (de) Horst Bechmann-Ziegler: Mundart-Wörterbuch unserer Heimat Neustadt b. Coburg [Dialect Wordbook of our Home, Neustadt bei Coburg]. Neustadt bei Coburg, 1991.

- (de) Horst Traut: Die Liederhandschrift des Johann Georg Steiner aus Sonneberg in der Überlieferung durch August Schleicher [The Manuscripts of the Traditional Songs of Johann Georg Steiner of Sonneberg from August Schleicher]. Rudolstadt, Hain, 1996, ISBN 3-930215-27-6.

- (de) Wolfgang Lösch: Zur Dialektsituation im Grenzsaum zwischen Südthüringen und Nordbayern [The Dialect Situation in the Borderlands between South Thuringia and North Bavaria]. In: Dieter Stellmacher (ed.): Dialektologie zwischen Tradition und Neuansätzen [Dialectology Between Traditional and New Approaches]. Zeitschrift für Dialektologie und Linguistik (ZDL)-Beiheft 109 (Journal of Dialectology and Linguistics (ZDL)- Supplement 109), Stuttgart 2000, pp. 156–165.

- (de) Karl-Heinz Großmann (ed.): Thüringisch-Fränkischer Mundartsalat [Atlas of the Thuringian and Franconian Dialects]. Self-publication of the AK Mundart Südthüringen e. V., Mengersgereuth-Hämmern 2004.

- (de) Karl-Heinz Großmann (ed.): Punktlandung. Self-publication of the AK Mundart Südthüringen e. V., Mengersgereuth-Hämmern 2007.

- (de) Karl-Heinz Großmann (ed.): 30 un kä wengla leiser. Self-publication of the AK Mundart Südthüringen e. V., Mengersgereuth-Hämmern 2009.

External links

- (de) Itzgründisch (Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena) (including the map of the boundaries of the speaking area)

- (de) Mundartlexikon auf Itzgründisch (between variations from the towns of Effelder and Rauenstein)

- (de) Discussions in the Sonneberger dialect

- (de) Itzgründisch by Subject