Comédie-Italienne

Comédie-Italienne or Théâtre-Italien are French names which have been used to refer to Italian-language theatre and opera when performed in France.

The earliest recorded visits by Italian players were commedia dell'arte companies employed by the French court under the Italian-born queens Catherine de Medici and Marie de Medici. These troupes also gave public performances in Paris at the theatre of the Hôtel de Bourgogne, probably the earliest public theatre to be built in France.

The first official use of the name Comédie-Italienne was in 1680, when it was given to the commedia dell'arte troupe at the Hôtel de Bourgogne, to distinguish it from the French troupe, the Comédie-Française, which was founded that year,[1] and just as the name Théâtre-Français was commonly applied to the latter, Théâtre-Italien was used for the Italians. Over time French phrases, songs, whole scenes, and eventually entire plays were incorporated into the Comédie-Italienne's performances. By 1762 the company was merged with the Opéra-Comique, but the names Comédie-Italienne and Théâtre-Italien continued to be used, even though the repertory soon became almost exclusively French opéra-comique. The names were dropped completely in 1801, when the company was merged with the Théâtre Feydeau.

From 1801 to 1878, Théâtre-Italien was used for a succession of Parisian opera companies performing Italian opera in Italian. In 1980 the name La Comédie-Italienne was used for a theatre in the Montparnasse district of Paris, which presents Italian commedia dell'arte plays in French translation.[2][3]

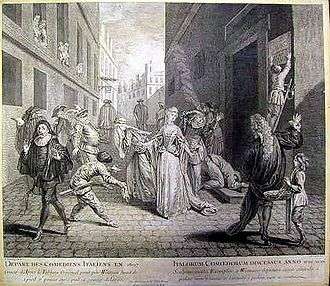

The Comédie-Italienne in the 17th century

In the 17th century, the historical Comédie-Italienne was supported by the king. At that time, a distinction was made between so-called legitimate theatre, which could be performed in royally-sanctioned theatres, and the more lowbrow street theatre, which did not undergo the scrutiny of royal censors. Italian troupes performed in the Hôtel de Bourgogne up to 1645, at which time they moved to Petit Bourbon. In 1660 they moved to the Palais-Royal, where they performed in alternation with the troupe of Molière. It was during this period that Tiberio Fiorillo, who was to have a strong influence on Molière, was the head of the Italian company. Both troupes, evicted from the Palais-Royal by Lully's Académie royale de Musique in 1673, moved to the Théâtre Guénégaud, where they continued to perform in alternation until the establishment of the Comédie-Française in 1680, at which time the Italians, now officially the Comédie-Italienne, returned to the Hôtel de Bourgogne, where they performed until the company was disbanded in 1697.[4]

The historical Comédie-Italienne presented to the French-speaking public spectacles performed by professional Italian actors. At first, these actors performed commedia dell'arte in their native Italian. Commedia dell'arte is an improvisational type of theatre; there were no scripts. They had multiple scenarios that they would pick from to perform, but inside that scenario they really did not have anything else planned out. They did however have specific character types, called Stock Characters, that became famous and loved by the theatre goers.

After moving to the Hôtel de Bourgogne in 1680 the troupe began presenting scripted plays by dramatists such as Regnard, Dufresny, and Palaprat.[5] Around the same time the troupe became widely popular, King Louis XIV gave the newly formed national theatre of France, the Comedie Francaise, a monopoly on spoken French drama. The royalty saw the troupe's cooperation with French playwrights as a threat and began to consider refusing the troupe their annual pension.

In 1697, a single event caused the King to finalize his decision. The actors had just announced upcoming performances of the play La fausse prude, or The False Hypocrite, a play that directly ridiculed King Louis XIV of France's wife, Madame de Maintenon. There is a debate among scholars as to whether or not the play was actually performed or if the play was simply advertised and the King learned of its existence. Regardless, upon his knowledge of the play's existence, the king had the actors sent away and the theatre shut down.

The Comédie-Italienne in the 18th century

After the period of mourning following the death of Louis XIV in 1715, the oppressive atmosphere of religious devotion characteristic of the latter part of his reign began to lift. Philippe d'Orléans, the Regent, was particularly desirous of restoring pleasure and amusement to the capital. He and his friends fondly remembered the Théâtre-Italien from twenty years previous. The main options for theatre in Paris at the time were the highly refined productions of the Comédie-Française or the "crude and tasteless" performances of the fair theatres. There was a need for theatrical comedy somewhere in between, with greater popular appeal than the Comédie-Française, but higher production values than those of the theatres at the fairs. In the spring of 1716 Philippe asked his cousin, the Duke of Parma, to send him a troupe of Italian actors to revive the Comédie-Italienne in Paris, which had been disbanded nearly twenty years previous. To avoid some of the difficulties of the earlier troupe, he specified that its leader should be a man of good character and manners. Luigi Riccoboni was chosen, and in a few weeks he assembled a group of ten actors, all of whom were devout Christians.[6]

Riccoboni's troupe performed at the Palais-Royal from 18 May 1716 until the Hôtel de Bourgogne had been renovated. Their first performance in the renovated Bourgogne theatre was on 1 June, when they performed La Folle supposée (La Finta Pazza) in Italian.[7] After an initial period of success, audiences dwindled, and the new company was also forced to begin performing more and more plays in French. Between 1720 and 1740 the company presented around 20 plays of Marivaux with great success.[5] The actress Silvia Balletti was particularly famous for her portrayals of Marivaux's heroines. As the competition from the fair theatres increased, the company began presenting similar fare, including French comédies-en-vaudevilles and opéras-comiques.[5]

In 1762, the company merged with the Opéra-Comique of the Théâtre de la Foire. The combined company opened at the Bourgogne on 3 February 1762 and continued to perform in the theatre until 4 April 1783, after which they moved to the new Salle Favart.[4] By this time all the Italian players had either retired or returned to Italy, and the traditional Comédie-Italienne had in effect ceased to exist.[5] The name Comédie-Italienne was used less and less and was completely abandoned in 1801, when the company merged with the Théâtre Feydeau.[8]

Italian opera in Paris in the 17th and 18th centuries

The first operas shown in Paris were Italian and were given in the mid-17th century (1645–1662) by Italian singers invited to France by the regent Anne d'Autriche and her Italian-born first minister, Cardinal Mazarin. The first was really a play with music, a comédie italienne, which may have been Marco Marazzoli's Il giudito della ragione tra la Beltà e l'Affetto, although this has been disputed. It was presented at Cardinal Richelieu's theatre, the Salle du Palais-Royal, on 28 February 1645. Francesco Sacrati's opera La finta pazza was presented at the Salle du Petit-Bourbon on 14 December 1645, and Egisto (probably a version of Egisto with music by Francesco Cavalli) was given at the Palais-Royal on 13 February 1646. A new Italian opera, Orfeo, with music composed by Luigi Rossi, premiered at the Palais-Royal on 2 March 1647.[9]

During the Fronde, Mazarin was in exile and no Italian works were performed, but after his return to Paris, Carlo Caproli's Le nozze di Peleo e di Theti was produced at the Petit-Bourbon on 14 April 1654. Cavalli's Xerse was given in the Salle du Louvre on 22 November 1660, and his Ercole amante premiered at the new Salle des Machines in the Tuileries Palace on 7 February 1662. These early Paris productions of Italian operas were usually tailored to French taste. Ballets with music by French composers were often interpolated between acts. They were also highly elaborate visual spectacles, several with numerous set changes and scenic effects accomplished with stage machinery designed by Giacomo Torelli. The visual spectacle enhanced their popularity with the French, who mostly did not understand Italian.[9]

Italian opera was abandoned in favour of French opera, not long after Louis XIV assumed power, as witnessed by the creation of the Académie d'Opéra in 1669. Despite this, over the course of the 18th century, Italian musical performers came to Paris. In particular, in 1752, performances of the opera buffa La serva padrona led to the Querelle des Bouffons, a debate about the relative superiorities of French and Italian musical traditions.

In 1787, after the particular success of one troupe of Italian singers, came the idea of establishing a resident theatrical company for opera buffa. This initiative became reality in January 1789 with the founding of the Théâtre de Monsieur company, which was soon put under the auspices of the Count of Provence, the king's brother, known at court as Monsieur. They first performed at the Tuileries Palace theatre, before moving to the Théâtre Feydeau. However, in 1792, the Italian troupe departed due to the upheaval of the French Revolution, but the theatre continued presenting French plays and opéra-comique.

The Théâtre-Italien in the 19th century

_03_012_1_Theater_Ventadour_in_Paris_%E2%80%93_Eine_Scene_aus_dem_zweiten_Acte_des_Don_Pasquale_(cropped).jpg)

A new Théâtre-Italien, performing Italian opera in Italian, was formed by Mademoiselle Montansier in 1801, when it was officially known as the Opera Buffa, but more familiarly as the Bouffons.[11] The company first performed at the Théâtre Olympique on the rue de la Victoire, but moved to the Salle Favart on 17 January 1802. Montansier retired on 21 March 1803.[12] From 9 July 1804 the company performed at the Théâtre Louvois, and from 16 June 1808, at the Théâtre de l'Odéon, at that time called the "Théâtre de l'Impératrice". They stayed there until 1815.[13]

During this early period the Théâtre-Italien first presented opera buffa by Domenico Cimarosa and Giovanni Paisiello, later adding those by Ferdinando Paër and Simone Mayr. The theatre commissioned Valentino Fioravanti’s I virtuosi ambulanti, first presented on 26 September 1807. Several of Mozart's operas were first presented in Italian in Paris by the company, including Figaro (23 December 1807), Così (28 January 1809), and Don Giovanni (2 September 1811), the last under Gaspare Spontini, who served as director from 1810 to 1812. Spontini also added opera serie by Niccolò Antonio Zingarelli and others.[14]

At the time of the Bourbon Restoration, King Louis XVIII wanted to entrust the theatre to the soprano Angelica Catalani. Almost everything was set for the transfer, when the return of Napoleon and his reign of a Hundred Days disrupted the King's plans. The actors therefore stayed a little longer at the Théâtre de l'Impératrice. Upon the restoration of King Louis XVIII to power, Madame Catalani joined the troupe. However, she soon went on a tour across Europe, leaving control of the theatre to Paër, who presented the first Rossini opera to be performed in Paris, L'Italiana in Algeri on 1 February 1817 in the first Salle Favart, although the production was so inferior, he was accused of "attempting to sabotage Rossini's reception in Paris."[15]

In 1818, Madame Catalani's privilège, or royal permission to perform, was revoked, and the theatre shut down. It was then decided to hand over administration of the theatre, now known as the Théâtre Royal Italien, to the Academie Royale de Musique (as the Paris Opéra was known at that time), while maintaining the autonomy of each establishment.[16] Paër again served as director from 1819 to 1824 and 1826 to 1827. From 1819 to 1825 the company performed at the Salle Louvois, which only accommodated 1100 spectators.[17] Several Paris premieres of Rossini operas were given there: Il barbiere di Siviglia (26 October 1819),[18] Torvaldo e Dorliska (21 November 1820),[19] Otello (5 June 1821),[20] and Tancredi (23 April 1822).[21] His operas were so popular, that some of his Paris premieres were given at the larger Salle Le Peletier, including La gazza ladra (18 September 1821), Elisabetta, regina d'Inghilterra (10 March 1822), Mosè in Egitto (20 October 1822), and La donna del lago (7 September 1824, produced under Rossini's supervision).[22]

Rossini himself had come to Paris by 1 August 1824[23] and became director of the Théâtre-Italien on 1 December 1824.[24] He revived eight of his earlier works, including Il barbiere di Siviglia and Tancredi. His last Italian opera, Il viaggio a Reims, was premiered by the company on 19 June 1825 but was not a success.[25] He also produced the first opera by Giacomo Meyerbeer to be performed in Paris, Il crociato in Egitto, on 25 September 1825. On 12 November 1825 the company moved from the Salle Louvois to the refurbished first Salle Favart,[24] where Rossini staged Semiramide (18 December 1825) and Zelmira (14 March 1826).[26] Under Rossini the troupe's singers included Giuditta Pasta, Laure Cinti-Damoreau, Ester Mombelli, Nicolas Levasseur, Carlo Zucchelli, Domenico Donzelli, Felice Pellegrini, and Vincenzo Graziani.[17] Paer resumed the directorship in November 1826,[24] and Rossini's attention turned to creating French operas at the Opéra. The Théâtre-Italien's association with the Opéra only lasted until October 1827, when it regained its independence from the crown and lost the appellation "Royal". Paër was replaced as director by Émile Laurent on 2 October.[27] Rossini continued to help the Théâtre-Italien to recruit singers, including Maria Malibran, Henriette Sontag, Benedetta Rosmunda Pisaroni, Filippo Galli, Luigi Lablache, Antonio Tamburini, Giovanni Battista Rubini and Giulia Grisi, and to commission operas, including Bellini’s I puritani (25 January 1835 at the first Salle Favart[28]), Donizetti’s Marino Faliero (12 March 1835 at the first Salle Favart[28]), and Saverio Mercadante's I briganti (22 March 1836).[29]

The Théâtre-Italien settled permanently in the Salle Ventadour in 1841. It saw the premiere of Rossini's Stabat Mater there in 1842. The Théâtre-Italien also produced popular works by Gaetano Donizetti and Giuseppe Verdi, but the theatre was later forced to close in 1878.

Despite the closing of the Théâtre-Italien, operas continued to be performed in Italian in Paris, sometimes at the Théâtre de la Gaîté or the Théâtre du Châtelet, but especially at the Opéra.

Venues of the 19th-century Théâtre-Italien

| Theatre[30] | Dates used | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Salle Olympique | 31 May 1801 – 13 January 1802 | Located on the rue de la Victoire.[31] |

| Salle Favart (1st) | 17 January 1802 – 19 May 1804 | |

| Salle Louvois | 9 July 1804 – 12 June 1808[32] | |

| Salle de l'Odéon (2nd) | 16 June 1808 – 30 September 1815 | |

| Salle Favart (1st) | 2 October 1815 – 20 April 1818 | |

| Salle Louvois | 20 March 1819 – 8 November 1825 | |

| Salle Favart (1st) | 12 November 1825 – 14 January 1838 | Destroyed by fire 14 January 1838. |

| Salle Ventadour | 30 January 1838 – 31 March 1838 | |

| Salle de l'Odéon (3rd) | October 1838 – 31 March 1841 | |

| Salle Ventadour | 2 October 1841 – 28 June 1878 | Final performance 28 June 1878. |

The modern Comédie-Italienne

The present-day theatre is La Comédie Italienne, situated on the rue de la Gaîté, where it was established in 1980 by the director Attilio Maggiulli.

Notes

- Hartnoll 1983, p. 168; Roy 1995, p. 233.

- "Historique du Théâtre" at La Comédie Italienne website.

- Forman 2010, p. 82.

- Wild 1989, pp. 100–101.

- Roy 1995, p. 234.

- Brenner 1961, pp. 1–2.

- Brenner 1961, pp. 2–3, 47.

- Hartnoll 1983, pp. 169–170.

- Powell 2000, pp. 21–23, 57; Anthony 1992.

- Wild 1989, pp. 229–232.

- Charlton 1992.

- Wild 1989, p. 195.

- Wild 1989, p. 196.

- Johnson 1992; Loewenberg 1978, cols 426 (Figaro), 452 (Don Giovanni), 478 (Così), 603 (I virtuosi ambulanti).

- Johnson 1992; Loewenberg 1978, col 633; Simeone 2000, p. 186.

- Wild 1989, p. 197.

- Johnson 1992.

- The libretto, listed at WorldCat (OCLC 456913691), gives the date as 23 September 1819, but Loewenberg 1978, col 643, says this is erroneous, rather it was actually performed on 26 October 1819.

- Libretto of Torvaldo e Dorliska at WorldCat. OCLC 461200086; Loewenberg 1978, col 642.

- Although the printed libretto of Otello (WorldCat OCLC 79827616) gives the date of the Paris premiere as 31 May 1821, Loewenberg 1978, col 649, gives 5 June 1821.

- The printed libretto listed at WorldCat (OCLC 458651003) gives the date as 20 April 1822, but Loewenberg 1978, col 629, gives 23 April 1822.

- Johnson 1992; Loewenberg 1978, cols 641 (Elisabetta, regina d'Inghilterra), 654 (La gazza ladra), 657 (Mosè in Egitto), 665 (La donna del lago); Gossett 2001.

- Gossett 2001.

- Wild 1989, p. 198.

- Johnson 1992; Loewenberg 1978, col 696.

- Johnson 1992; Loewenberg 1978, cols 682 (Zelmira), 686 (Semiramide); Simeone 2000, p. 186 (Semiramide at the first Salle Favart).

- Wild 1989, pp. 198–199.

- Simeone 2000, p. 186.

- Johnson 1992; Loewenberg 1978, cols 764 (I puritani), 779 (I briganti).

- The information in the table is from Wild 1989, pp. 194–209; Charlton, 1992, pp. 867, 870–871.

- Barbier (1995), pp. 174–175.

- Charlton, 1992, p. 867, gives the date 4 August 1808.

Bibliography

- Anthony, James R. (1992). "Mazarin, Cardinal Jules", vol. 3, p. 287, in The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, 4 volumes, edited by Stanley Sadie. London: Macmillan. ISBN 9781561592289.

- Baschet, Armand (1882). Les comédiens italiens à la cour de France sous Charles IX, Henri III, Henri IV et Louis XIII. Paris: Plon. Copy at Google Books; Copies 1 & 2 at Internet Archive.

- Boquet, Guy (April–June 1977). "La Comédie Italienne sous la Régence: Arlequin poli par Paris (1716-1725)". Revue d'histoire moderne et contemporaine (in French). 24 (2): 189–214. doi:10.3406/rhmc.1977.973. JSTOR 20528392.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Boquet, Guy (July–September 1979). "Les comédiens Italiens a Paris au temps de Louis XIV". Revue d'histoire moderne et contemporaine (in French). 26 (3): 422–438. doi:10.3406/rhmc.1979.1065. JSTOR 20528534.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Boudet, Micheline (2001). La Comédie Italienne: Marivaux et Silvia. Paris: Albin Michel. ISBN 9782226130013.

- Brenner, Clarence D. (1961). The Théâtre Italien: Its Repertory, 1716–1793. Berkeley: University of California Press. OCLC 2167834.

- Brooks, William (October 1996). "Louis XIV's Dismissal of the Italian Actors: The Episode of 'La Fausse Prude'". The Modern Language Review. 91 (4): 840–847. doi:10.2307/3733512. JSTOR 3733512.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Campardon, Émile (1880). Les comédiens du roi de la troupe italienne (2 volumes). Paris: Berger-Levrault. Copies at Internet Archive.

- Castil-Blaze (1856). L'Opéra italien de 1645 à 1855. Paris: Castil-Blaze. Copies at Internet Archive.

- Charlton, David (1992). "Paris. 4. 1789–1870. (v) The Théâtre Italien", vol. 3, pp. 870–871, in The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, 4 volumes, edited by Stanley Sadie. London: Macmillan. ISBN 9781561592289.

- Di Profio, Alessandro (2003). La révolution des Bouffons. L'opéra italien au Théâtre de Monsieur, 1789–1792. Paris: Éditions du CNRS. ISBN 9782271060174.

- Forman, Edward (2010). Historical Dictionary of French Theater. Lanham: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810849396.

- Gherardi, Evaristo, editor (1721). Le Théâtre Italien de Gherardi ou le Recueil général de toutes les comédies et scènes françoises jouées par les Comédiens Italiens du Roy ... 6 vols. Amsterdam: Michel Charles le Cène. Vols. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 at Google Books.

- Gossett, Philip (2001). "Rossini, Gioachino, §5: Europe and Paris, 1822–9" in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd edition, edited by Stanley Sadie. London: Macmillan. ISBN 9781561592395 (hardcover). OCLC 419285866 (eBook). Also at Oxford Music Online (subscription required).

- Hartnoll, Phyllis, editor (1983). The Oxford Companion to the Theatre (fourth edition). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192115461.

- Johnson, Janet (1992). "Paris, 4: 1789–1870 (v) Théâtre-Italien", vol. 3, pp. 870–871, in The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, edited by Stanley Sadie. New York: Grove. ISBN 9781561592289. Also at Oxford Music Online (subscription required).

- Loewenberg, Alfred (1978). Annals of Opera 1597–1940 (third edition, revised). Totowa, New Jersey: Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 9780874718515.

- Origny, Antoine d' (1788). Annales du théâtre italien depuis son origine jusqu'à ce jour (3 volumes). Paris: Veuve Duchesne. Reprint: Geneva: Slatkine (1970). Vols. 1, 2, and 3 at Google Books.

- Powell, John S. (2000). Music and Theatre in France 1600–1680. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198165996.

- Roy, Donald (1995). "Comédie-Italienne", pp. 233–234, in The Cambridge Guide to the Theatre, edited by Martin Banham. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521434379.

- Scott, Virginia (1990). The Commedia dell'Arte in Paris, 1644–1697. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia. ISBN 9780813912554.

- Simeone, Nigel (2000). Paris – A Musical Gazetteer, p. 239. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300080537.

- Soubiès, Albert (1913). Le théâtre italien de 1801 à 1913. Paris: Fischbacher. Copy at Internet Archive.

- Wild, Nicole ([1989]). Dictionnaire des théâtres parisiens au XIXe siècle: les théâtres et la musique. Paris: Aux Amateurs de livres. ISBN 9780828825863. ISBN 9782905053800 (paperback). View formats and editions at WorldCat.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Comédie-Italienne. |

- Le théâtre italien à Paris

- List of all the performances at the Comédie-Italienne from 1783 to 1800 on the site CÉSAR