Iskandar (Timurid dynasty)

Iskandar Mirza (1384 – 1415) was a member of the Timurid dynasty and the grandson of its founder, the Central Asian conqueror Timur. Iskandar was among the princes who attempted to claim the throne in the aftermath of Timur's death. He became a prominent ruler and was notable for his strong interest in culture and learning. He was defeated by his uncle Shah Rukh and later executed during a rebellion attempt.

| Iskandar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timurid Prince | |||||

| Born | 25 April 1384 Uzgand, Fergana, Timurid Empire | ||||

| Died | 1415 (aged 30–31) | ||||

| Wives | Biki Sultan (daughter of Miran Shah) Jan Malik Shiraz Malik Mughul | ||||

| Issue | Pir Ali Sultan Ali Mahdi Shahzade Unnamed son | ||||

| |||||

| House | House of Timur | ||||

| Father | Umar Shaikh Mirza I | ||||

| Mother | Malikat Agha | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

Background

Iskandar was born on 25 April 1384 and was the second son of Umar Shaikh Mirza I by his wife, the Mongol princess Malikat Agha. His father was the eldest of the four sons of Timur and his mother was a daughter of the Khan of Moghulistan, Khizr Khoja.[1][2]

Early life and career

Upon his father's appointment as viceroy of Fars in 1393, Iskandar and his family were transferred from his birthplace of Uzgand to join Umar Shaikh at Shiraz. Soon after, both his father and elder brother Pir Muhammad were summoned to re-join the Timurid army, leaving the young Iskandar as the nominal governor in Umar Shaikh's stead. Upon the latter's death the following year, this role was given to Pir Muhammad while Iskandar and other family members accompanied Umar Sheikh's bier for burial in Kesh.[2]

In 1397, following his marriage to his cousin Biki Sultan (daughter of Miran Shah by his wife Khanzada), Iskandar and his amirs were assigned to Ferghana. It was from here, in the winter of 1399/1400, he launched an unauthorised raid into neighbouring Moghulistan.[2] Though this incursion was successful, it earned Iskandar the enmity of his older cousin, the crown-prince Muhammad Sultan. This was due to Iskandar having drawn from the latter's troops, forcing a hiatus on Muhammad Sultan's own planned expedition.[3]

This grudge between the two princes climaxed in outright hostilities the following year. Muhammad Sultan, now serving as their grandfather's deputy while he was away on campaign, captured Iskandar and his entourage and had them tried in Samarqand. This resulted in Iskandar's atabeg Bonyān Tīmūr and twenty-six of his companions being executed, with the prince himself being imprisoned for a year. Timur's reaction to these developments upon his return are contradictory. One account states that Timur upheld Iskandar and blamed Muhammad Sultan for the dispute, ordering restitution for the executed nobles. Another says that Timur sided with the latter and, after having Iskandar tried once more, had his feet whipped as punishment.[4][2] Iskandar subsequently accompanied his grandfather on his campaigns in Anatolia and Caucasia, before being given rule over Hamadan and Lor-e Kūček.[2]

Upon Timur's death in 1405, order in the region began to deteriorate. Iskandar took refuge with Pir Muhammad, now the ruler of Fars,[5] who named him governor of Yazd.[6] However, the two became alienated when Iskandar launched an invasion of Kerman, alarming his brother. He was captured by Pir Muhammad, who then confiscated his territory.[7] Iskandar soon escaped and allying himself with their other brother Rustam, launched a failed siege of Pir Muhammad's capital of Shiraz. The latter in turn captured Rustam's capital of Isfahan, forcing the two princes out of the region.[8] Iskandar wandered for sometime following this, before eventually being captured and taken to the court of Shah Rukh in Herat. Shah Rukh, who was both uncle and stepfather to the brothers,[9] dispatched Iskandar to Shiraz, bearing a letter to Pir Muhammad requesting a pardon for the young prince.[10]

Ascension and reign

By 1409, Iskandar had reconciled with Pir Muhammad, having agreed to serve his brother in a subordinate position and accompanying him on an expedition against Kirman. However, during this time, Pir Muhammad was murdered in an attempted coup.[8] In order to avoid the same fate, Iskandar fled to Shiraz on horseback, wearing only his shirt, a cap and a single boot. The city nobles acclaimed him their ruler and he had Pir Muhammad's killers executed.[11] Iskandar sent his agents to Yazd, taking the city after several months of siege. Isfahan took longer to capture, as he vied for control of the city with alternating rulers, including Rustam. In 1411/12 however, it too capitulated.[8] Iskandar named the city his new capital, and the following year adopted the title of sultan. At the same time, he expanded his rule over the cities of Qom and Saveh, a feat which his predecessors had failed to achieve.[8]

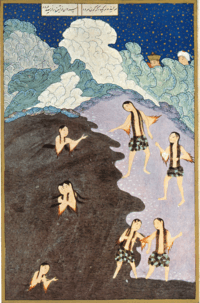

Even before gaining true regnal power, Iskandar showed himself to be an individual of broad intellectual and cultural interests. When he had first gained Shiraz in 1409, he gathered prominent religious figures to his court, such as the theologian Al-Sharif al-Jurjani and the poet Shah Nimatullah Wali. Later on, he also invited eminent personages from many other subjects, such as astronomy. At the same time, Iskandar began an extensive patronage of book production, resulting in the creation of albums, anthologies of historical and scientific writings, and poetry in Persian, Turkic and Arabic. A major building campaign was also initiated during his rule.[12]

Throughout this time Iskandar, though under the nominal suzerainty of Shah Rukh, essentially acted as an independent ruler.[9] By 1413/14, Iskandar's ambitions had brought him into direct conflict with Shah Rukh. Troubled by reports from his nephew's realm, Shah Rukh sent an emissary to invite him in a joint-expedition against the Qara Qoyunlu, a pretext to have Iskandar recognise his authority. The emissary instead returned bearing news that the prince was minting coinage in his own name. At this time, Iskandar began rallying local rulers to support him in a fight against his uncle. In response, Shah Rukh marshalled his forces in a campaign against Iskandar, with the latter's brothers, Rustam and Bayqara, in his train.[13][9] On 21 July 1414, Iskandar was defeated and captured at Isfahan, with the city submitting to Shah Rukh after a short siege. The prince's lands were distributed among various Timurids, including Bayqara, who received Hamadan and Luristan, and Rustam, who had Isfahan returned to him.[13] The latter was also given custody of Iskandar, who he subsequently had blinded.[9]

Death

At Shah Rukh's command, Iskandar was later transferred to the care of Bayqara.[9] In 1415, Iskandar persuaded his captor to launch his own rebellion against their uncle. However, this act of sedition proved one too many for Iskandar, who was captured by Qashqa'i nomads near Gandoman and handed over to Rustam, who had him executed in November of that year.[14][2]

References

- Woods (1990), pp. 2, 14, 23.

- Soucek (1998).

- Barthold (1963), p. 51.

- Barthold (1963), p. 35.

- Ferrier (1989), p. 205.

- Manz (2007), p. 29.

- Manz (2007), p. 157.

- Manz (2007), p. 30.

- Glassen (1989).

- Brend (2013), p. 44.

- Manz (2007), p. 159.

- Manz (2007), pp. 30-31.

- Manz (2007), p. 31.

- Manz (2007), p. 163.

Bibliography

- Barthold, Vasilii Vladimirovitch (1963), Four Studies on the History of Central Asia, 2, Leiden: E.J. Brill

- Brend, Barbara (2013), Perspectives on Persian Painting: Illustrations to Amir Khusrau's Khamsah, Routledge, p. 44, ISBN 978-1-136-85411-8

- Ferrier, Ronald W. (1989), The Arts of Persia, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-03987-0

- Glassen, E. (December 15, 1989), "BĀYQARĀ B. ʿOMAR ŠAYḴ", Encyclopaedia Iranica, Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation, retrieved July 25, 2019

- Manz, Beatrice Forbes (2007), Power, Politics and Religion in Timurid Iran, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-139-46284-6

- Soucek, Priscilla (December 15, 1998), "ESKANDAR SOLṬĀN", Encyclopaedia Iranica, Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation, retrieved December 7, 2019

- Woods, John E. (1990), The Timurid dynasty, Indiana University, Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies