Isabella Parasole

Isabella Parasole (ca. 1570 – ca. 1620) was an Italian engraver and woodcutter of the late-Mannerist and early-Baroque periods.

Isabella Parasole | |

|---|---|

_MET_DP358053_(cropped).jpg) Portrait from the titlepage of Teatro delle Nobili et Virtuose Donne | |

| Born | circa 1575 |

She was born and active in Rome. She married the engraver Leonardo Norsini, who took his wife's more distinguished last name. Her sister, Geronima Parasole, was also an engraver and made a woodcut of Antonio Tempesta's Battle of the Centaurs. Isabella executed several cuts of plants for an herbal, published under the direction of Federico Cesi, of Acquasparta. She published a book in 1597 called Studio delle Virtuose Dame, dedicated to Juana de Aragón y Cardona (1575–1608), and in 1616 she published another book on the methods of working lace and embroidery, with ornamental cuts, which she engraved from her own designs.[1][2] She dedicated that book to Elisabeth of France (1602–1644), and called herself also Elisabetta as the author.

Her son Bernardino Parasole became a pupil of Giuseppe Cesari, but died young. She was working at Rome about 1600, and died there in her 50th year.

Early Career

Parasole was commissioned to create illustrations for Castore Durante’s Herbario Nuovo. This treatise was so popular that it was reprinted several times shortly following its release. Her husband, Leonardo, created the woodblocks used to print her illustrations in the publication. Parasole’s designs in this piece were very similar to those in many of the most prominent botanical treatises of the time, mainly I discorsi and De historia stirpum commentarii insignes.

Despite the many similarities, her illustrations were not without obvious creativity. While she maintained the typical portrayals of each plant, she took her own liberties of modifying landscapes as she saw fit. Some of her illustrations included people while others consisted of plants within a garden or a pot. She also added animals, hills and other environmental factors to display her originality and skill.[3]

Mid-Late Career

Following her illustrations on Herbario Nuovo, Parasole was invited to work with Prince Frederico Cesi. Many of the illustrations in Rerum medicarum Novae Hispaniae thesaurus, a large work compiled by Prince Cesi and others in the scientific community, resembled the Parisole’s style in Herbario Nuovo without her creativity and extreme attention to detail.[3]

She gathered much of her inspiration from the famed botanical garden of Prince Cesi of Acquasparta.[4] Many of her designs in her lace books consisted of floral patterns, likely from this garden. Parasole also worked on many illustrations for Prince Cesi. Unfortunately, none of her illustrations have been recovered. Many of her lace pattern books, however, have been and are on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.[5]

Parasole was one of the first and most prominent textile pattern designers of her time. Her first publication, Spechio delle Virtuose Donne, published by Antonio Fachetti, was the first full pattern book to be designed by a woman. As a pioneer in her field, Parasole’s work was astonishing. She demonstrated immense understanding of the composition of the lace with which her readers would work and follow her original designs. [6]

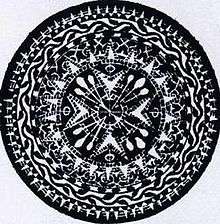

Teatro delle nobili et virtuose donne

Parasole’s most famous work was Teatro delle nobili et virtuose donne, a 1616 publication containing a plethora of embroidery and lacework designs.[3] Teatro delle nobili et virtuose donne contains a design consisting of a floral pattern of a large, round flower at the center, surrounded on four corners by a smaller floral design contained within a square. This design is repeated throughout the piece, separated by yet another floral pattern in between occurrences. The centerpiece consists of sixteen petals, while the complementing designs consist of four petals each. This evokes a beautiful symmetry within each segment of the piece, as well as throughout the piece as a whole. The entire work contains a variety of other designs, including some that are rather similar to this particular design. Many of her designs in Teatro delle nobili et virtuose donne have been used in forms of elegant decorations such as carpets and tapestries.[7]

Overview of Lace Work/Pattern Books

The techniques of lace work developed rapidly throughout the middle of the sixteenth century. In the early sixteenth century, lace work consisted of “simple patterns of drawn threads or cut-work.” These types of works composed books such as the Zoppino (1529) and the Vavassore (1532). Towards the latter part of the sixteenth century, lace work became more elegant as more intricate floral designs became possible through new techniques not confined to the traditional rectangular cloths. Parasole excelled in designing these types of patterns.[5]

Textile pattern books were often aimed at a feminine audience. In Italy, it was tradition for mothers to pass on lace books to their daughters. One work, Ornamento, crerated by Matteo Pagano ended with the poem “If beauty and honesty make you shine like the stars in heaven, virtue will make you even more beautiful.” Many pattern books after this did similar things to encourage their largely female audience to participate in lace work, often comparing them to famous poets, painters, and other artists. Most women were rather unsuccessful in their own needlework efforts, however, Parasole perfectly exemplifies what these men encouraged women to become.[6]

Personal Life

Parasole’s childhood is largely a mystery, however, her name implies that she was born near Sicily, Italy.[6]

Isabella Parasole married Leonardo Norsini, an Italian artist himself. Norsini decided to take his wife’s surname in marriage due to it being far more distinguished than his own.[5] He engraved many of the blocks needed in order to print her illustrations for Herbario Nuovo.[3]

Her sister, Geronima, was also an artist who worked with engravings and is most known for her woodcut of Antonio Tempesta’s Battle of the Centaurs.[4]

She had one son, Bernardino, who studied under Giuseppe Cesari before an untimely death.[4]

Works on Display

| Title | Date | Medium | Dimensions | Classifications | Museum |

| Studio delle virtuose Dame | 1597 | Woodcut | 14 x 20.5 cm | Book | The Met |

| Pretiosa Gemma delle virtuose donne | 1600 | Woodcut | 12 x 17 cm | Book | The Met |

| Fiore D’Ogni Virtu Per le Nobili Et Honeste | 1610 | Woodcut | 20 x 26 cm | Book | The Met |

| Teatro delle Nobili et Virtuose Donne | 1616 | Woodcut, engraving | 19 x 26.5 cm | Book | The Met |

| Gemma pretiosa della virtuose donne | 1625 | Woodcut | 13.5 x 19.5 cm | Book | The Met[8] |

References

- Studio delle virtuose Dame, Rome, 1597

- Teatro delle nobili et virtuose donne dove si rappresentano varij Disegni di Lauori nouamente Inuentati, et disegnati da Elisabetta Catanea Parasole, Rome, 1616

- TOMASI, LUCIA TONGIORGI (2008). ""La femminil pazienza": Women Painters and Natural History in the Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Centuries". Studies in the History of Art. 69: 158–185. ISSN 0091-7338. JSTOR 42622437.

- "Isabella Parasole". Europeana Collections. Retrieved 2019-03-25.

- "Lace Pattern Books of the Sixteenth Century". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 14 (4): 86–89. 1919. doi:10.2307/3253572. ISSN 0026-1521. JSTOR 3253572.

- Speelberg, Femke (2015). "Fashion & Virtue: TEXTILE PATTERNS AND THE PRINT REVOLUTION 1520–1620". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 73 (2): 1–48. ISSN 0026-1521. JSTOR 43824744.

- Wardle, Patricia (2003). ""Wrought with cuttworke": Een stel 17de-eeuwse textilia". Bulletin van Het Rijksmuseum. 51 (4): 336–357. ISSN 0165-9510. JSTOR 40383372.

- "Search / All results; 198 results for 'Isabella parasole'". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2019-03-25.

- University of Arizona On-Line Digital Archive of Documents on Weaving and Related Topics, E. Parasole, Stickhereien und Spitzen 1616

- Bryan, Michael (1889). Walter Armstrong & Robert Edmund Graves (ed.). Dictionary of Painters and Engravers, Biographical and Critical (Volume II L-Z). York St. #4, Covent Garden, London; Original from Fogg Library, Digitized May 18, 2007: George Bell and Sons. p. 251.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Parasole Biography in Web Gallery of Art

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Isabella Parasole. |