Isabel Pell

Isabel Townsend Pell (September 28, 1900 – June 5, 1951) was an American socialite and member of the French Resistance during World War II. She was subsequently decorated with the Legion of Honour.[1]

Isabel Pell | |

|---|---|

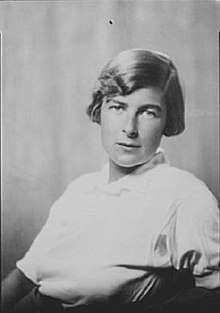

Pell in 1930 photographed by Arnold Genthe | |

| Born | Isabel Townsend Pell September 28, 1900 |

| Died | June 5, 1951 (aged 50) |

| Occupation | Socialite |

| Known for | Serving with the French Resistance |

| Partner(s) | Claire Charles-Roux, Marquise De Forbin |

Early life and family

_Repository.jpg)

Pell was born on September 28, 1900, to Samuel Osgood Pell (1875–1913), a New York real estate agent, and Isabel Audrey Townsend (1881–1958), who married October 18, 1899, in Babylon. The marriage was mentioned in the New York Times,[2] but was short-lived; Isabel Townsend was granted a divorce in early February 1902, aged 20. She remarried twice, initially to John Cotton Smith, descendant of politician John Cotton Smith.[1][3]

Pell's father died in an automobile accident on the night of August 3, 1913, when a train from the Long Island Railroad crashed into his car at a crossing. Isabel Townsend sued for $250,000, but both she and her daughter were left penniless. Pell was cared for by her paternal uncle, Stephen Hyatt Pell (1874–1950) and raised at Fort Ticonderoga, the family mansion on Lake Champlain. The house is on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places and a U.S. National Historic Landmark.[4][3] Her other uncle was tennis player Theodore Pell.[5]

Pell attended Holton-Arms School in Bethesda, Maryland, and the Spence School in New York City. She made her debut in 1920, at the Piping Rock Club, and was known as a skilled horsewoman in Long Island, New York, and Virginia.[6] She was nicknamed "Pelly" and admired by contemporaries for being outspoken and athletic.[1][3]

Career

.jpg)

In 1921, Pell went to work in a dress shop, a position felt to be below her social standing. In 1922 she quit to become an actress, playing a small part in Fools Errant at the Maxine Elliott Theatre.[1][3]

In 1930, Pell worked for the real estate firm Pell and MacMillen in New York.[7] She collaborated with the fashion writer Lois Long and the interior decorator Elsie de Wolfe.[8]

While in France during World War II, Pell took the name of "Fredericka" and joined the Maquis. She moved inland in the mountain and served for four years, until September 1944, and was known among the resistance as "the girl with the blonde mèche (lock)".[9] Pell was captured by Italian soldiers and interned at Puget-Théniers, but continued to smuggle information to the resistance during her daily walks at the camp. When she was released, she disguised herself as a peasant and went to a mountain forest with her lover, the Marquise Claire Charles-Roux De Forbin (1908–1992). A report in the Associate Press recounts how, in 1944, Pell rescued a contingent of American soldiers surrounded by the enemy in Tanaron. Pell was wearing the badge of Free France and came out from her hiding place, leading the men to safety.[3][1][10][11]

On November 28, 1944, the plaza in Puget-Théniers was renamed in her honor.

Personal life

_attending_a_tennis_tournament_with_her_date%2C_Isabel_Pell%2C_in_the_1920s.jpg)

In February 1924, Pell was briefly engaged to R. Lorenzo Thomson; the marriage was supposed to take place on June 3, 1924 but never happened.[5]

Society photos show Pell practicing sports, or together with other heiresses, like Margarett Sargent (1892–1978) and Eleonora Sears (1881–1968), both rumored to be her lovers.[12] Sargent said that Isabell was "handsome, wonderfully handsome". Pell used to visit Sargent at her Prides Crossing, Beverly, Massachusetts mansion, and was well known by both Sargent's husband, Quincy Adams Shaw McKean (1891–1971), and children, who called Pell "cousin Pell".[3][13][14]

In 1933 Isabel Pell and another woman, the wife of Henry T. Fleitmann, a partner of De Witt, Fleitmann & Company, were rescued after a flight between Copenhagen and Faleknberg crash-landed into the Kattegat. They were rescued by a German freighter and taken to Copenhagen, uninjured.[15]

Pell was friends with Eva Le Gallienne (1899–1991); the pair spent time together driving in the country.[16]

Pell had an affair with Renee Prahar, an American sculptor and actress with Bohemian ancestry. She was forced to leave New York after an affair with a Metropolitan Opera soprano became public. She moved to Paris, joining many other eccentric heiresses who sought freedom.[3] In a story recounted by Esther Murphy Strachey, younger sister of Gerald Murphy, Pell, with Natalie Clifford Barney, infiltrated a 13th-century Italian convent to meet with Alice Robinson.[17]

In France, Pell started a relationship with Claire Charles-Roux, Marquise De Forbin. The Marquise was born in Avignon but raised in Morocco. The couple moved to Auribeau-sur-Siagne. When France was occupied in 1940, both Pell and De Forbin joined the French Resistance and then the 1st Airborne Task Force (Allied) led by Major General Robert T. Frederick, who said "I think she came up there because she wanted a uniform. Well, we told her we didn't have any women's uniforms".[3][18] Pell became an attaché of the Civil Affair Task Force of the US Army and liaised between the French and the Americans.[19]

Pell was close friends with Mercedes de Acosta.[3][20] After the war De Acosta visited Pell in France and began a relationship with Pell's companion, Claire de Forbin.[21]

After the war, Pell moved back to New York City at 30 East End Avenue. She died at the age of 51, collapsing while dining with her friend Anne Andrews at La Reine Restaurant, 139 East 52nd Street.[3][1]

Legacy

We Used to Own the Bronx: Memoirs of a Former Debutante is a memoir written by Eve Pell, a reporter in San Francisco.[3][22]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Isabel Pell. |

- "Isabel Pell Dies: Served in Maquis" (PDF). The New York Times. 6 June 1952. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Marriages". New York Times: 7. 17 October 1899.

- Pell, Eve. "La Femme à la Mèche Blonde". Ms. Magazine. Archived from the original on 23 July 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "FOUR WATCHED PELL SPEEDING TO DEATH; Witnesses Describe How They Foresaw Auto Would Be Hit at Crossing. ASSERT TRAIN WAS LIGHTED Some Say They Heard Whistle Blown, but Others Are Not Sure – Trial Nearing End". The New York Times. 22 June 1915. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Engagements". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle: 7. 6 February 1924. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Harper's Bazaar, Volume 55. Hearst Corporation. 1920. p. 64. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Cades, Hazel Rawson (1930). Jobs for Girls. Harcourt, Brace. p. 76. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Ladies' Home Journal, Volume 48". Ladies' Home Journal. 48: 186. 1931. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Town & Country, Volume 97. Hearst Corporation. 1942. p. 31. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Kundahl, George G. (2017). Riviera at War: World War II on the Côte d'Azur. I.B.Tauris. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Rossiter, Margaret L. (1986). Women in the resistance. Praeger. p. 123. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Mitchell, John Ames (1930). "Life, Volume 95, Part 2". Life. 95, Part 2. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- The Advocate Num. 762. Here Publishing. 23 June 1998. p. 79. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Moore, Honor (2009). The White Blackbird: A Life of the Painter Margarett Sargent by Her Granddaughter. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 174. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "The Evening News". 28 August 1933: 1. Retrieved 1 August 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Sheehy, Helen (1996). Eva Le Gallienne: a biography. Knopf. p. 95. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Cohen, Lisa (2012). All We Know: Three Lives. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 75. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Adleman, Robert H.; Walton, George H. (1969). The champagne campaign. Little, Brown. p. 199. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Nelson, Michael (2008). Americans and the Making of the Riviera. McFarland & Company. p. 155. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- de Acosta, Mercedes (1975). Here lies the heart. Arno Press. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Schanke, Robert A (2004). That Furious Lesbian: The Story of Mercedes de Acosta. SIU Press. p. 151. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Pell, Eve (2009). We Used to Own the Bronx: Memoirs of a Former Debutante. SUNY Press. Retrieved 1 August 2017.