Iranians in Japan

Iranians in Japan (Japanese: 在日イラン人, Zainichi Iranjin, Persian: ایرانیان در ژاپن) form Japan's fifth-largest community of immigrants from a Muslim-majority country. They make up part of the Iranian diaspora. As of 2000, Japanese government figures recorded the population of legal Iranian residents at 6,167 individuals, with a further 5,821 estimated to be residing in the country illegally.[2][3]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 11,988 (2000) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Tokyo, Nagoya | |

| Languages | |

| Japanese, Persian | |

| Religion | |

| Shia Islam,[1] Baha'i Faith, Zoroastrianism, folk religion |

Migration history

A noteworthy Iranian influence exists on Japan.[4][5] Iranian nomads, like the Scythians, are suggested to have influenced the Japanese culture and its aristocratic system.[6] A number of historians also suggest that some Japanese clans are originally of Persian origin and were granted the title of local feudal lords. Scythian and especially Persian art had an impact on Japan during the Kofun period. Persian influence is also noted in the Kingdom of Silla.[7][8][9]

A 7th-century wooden writing tablet (called a Mokkan), found in Nara in the 1960s, and recently deciphered, mentioned a local resident who came from the Persian empire.[10][11][12]

As early as the 17th century, it was known that some of Persian merchants living in the Ayutthaya Kingdom (modern-day Thailand) had contacts with the Japanese community there, inspiring them to travel to Nagasaki for purposes of trade. Ever since the murder of Yamada Nagamasa in 1630, Japan's bakufu government had banned trading contact with Thailand's Ayutthaya Kingdom, but the trade continued clandestinely, on Ayutthaya ships manned with Chinese and Persian sailors.[13]

The number of Iranians in Japan began to expand significantly in 1988, after the cessation of hostilities in the Iran–Iraq War. Demobilized Iranian soldiers became involved in shuttle trade, buying electronics in Tokyo and smuggling them back to Iran to sell at high prices; due to a mutual visa exemption agreement between Japan and Iran, concluded in 1974, they were able to enter and exit Japan freely.[14] As word spread about the favourable economic conditions in Japan, increasing number of Iranians took advantage of visa-free entry to find jobs and settle in Japan; they were attracted by wages which remained high compared to Iran even after the 1990 bursting of the Japanese asset price bubble, and relatively lax enforcement of immigration policy.[15][16] In those days, Iran Air had only one flight per week going to Tokyo; during the peak period, prospective migrants had to book their tickets several years in advance.[17] However, in 1992, prompted by worsening economic conditions, Japan terminated the visa-free agreement with Iran, and began serious efforts to deport illegal overstayers. Though small numbers of Iranians turned to people smugglers to gain entrance to Japan, the total size of the Iranian population in Japan would shrink dramatically over the following decade, as the number of new migrants remained small compared to the number of deportations.[18]

Demographics and distribution

Iranians in Japan reside mostly in the Greater Tokyo Area; 79% of legal Iranian residents are registered in the Kantō region, with 1,464 in Tokyo itself, 798 in Kanagawa, 740 in Chiba, 701 in Saitama, 472 in Ibaraki, 387 in Gunma, and 352 in Tochigi. A further 6% can be found in the Chūkyō Metropolitan Area, with 255 in Aichi, 72 in Mie, and 62 in Gifu; the others are scattered throughout the rest of the country in small numbers.[19] 2,191 hold permanent residency visas, 195 are international students, and 2,858 hold short-term traineeship or employment visas, while the remainder of legal residents hold other kinds of visas.[2] Iranians used to form Japan's largest population of illegal immigrants, with an estimated peak of 32,994 individuals in 1992 (based on cumulative analysis of entrance statistics), but due to aggressive deportations, that number fell by over 82% to just 5,821 in 2000.[3]

Like other labour migrants from Muslim countries, most Iranians in Japan are middle-aged; 76% are between 30 and 40 years old, while only 6% are younger than 20 and less than 3% are older than 50.[20] The overwhelming majority are male; most were single, in their 20s or 30s, and had never travelled abroad before at the time of their migration, and even the married ones typically came unaccompanied by family members. Most were urban residents in Iran prior to their migration; many came from the same neighbourhoods of southern Tehran. They mostly were Persian-speakers.[17] Iranian migrants to Japan were less educated compared to other Muslim groups, such as Bangladeshis; less than 2% of one sample of 120 former Iranian migrants in Japan who had returned to Iran had any university or college education; 73.1% had terminated their education at the pre-tertiary level. While in Japan, they remitted an average of US$712/month.[21] Most worked in the construction industry; after the bursting of the bubble decreased opportunities for this kind of work, many became itinerant vendors near train stations; they became especially well-known and often stereotyped for selling illegal telephone cards.[22]

Community spaces

Initially, public parks served as the most important gathering points for the Iranian community; Ueno Park and Yoyogi Park were the most commonly frequented by Iranian migrants. Many set up small stands selling imported Iranian products; Japanese and Iranian brokers also could often be found in the park, helping new arrivals find jobs in exchange for a fee. However, complaints from neighbours and negative media coverage of illegal drug and fake telephone card sales in the parks resulted in an increased police presence in the parks; immigration officers also began to conduct regular sweeps of the parks in order to find and arrest individuals lacking proper documentation. Iranians themselves increasingly avoided the parks, hoping to avoid being stereotyped and lumped together with the so-called "bad Iranians" who assembled there regularly. As a result, the importance of public parks in the Iranian community declined.[23]

With the parks effectively closed off to communal gatherings, mosques began to take over some of the same functions. As in Iran itself, most Iranians in Japan are followers of Shia Islam. In the early days of their migration, Iranian migrants lacked the funds to establish their own mosque; as a result, they often used the prayer facilities at the Iranian embassy in Tokyo. Later, they established a mosque in Kodenma-chō, Chūō-ku; the management board was dominated by Iranians, but also had representatives of other nationalities. The mosque also serves as a community gathering point on non-Islamic holidays, especially Nowruz.[24]

Return to Iran

Due to their inability to legalise their visa situation, 95% of Iranian migrants to Japan eventually returned to Iran; only a few, typically those who married Japanese citizens or found an employer who could sponsor their visa application, were able to stay. Unlike return migrants to traditional labour-exporting countries, most Iranians who return home from Japan find that they have no further opportunities to go abroad in search of higher wages in order to maintain their increased living standards or save more money.[25] Iranian migrants stayed in Japan for an average of four years before returning home, during which time they remitted US$33,680. Most used that money to purchase their own dwellings in Iran, or to start their own businesses.[26] The money earned while abroad contributed significantly to social mobility; 57% of one sample of 120 returnees were able to use their savings to start their own businesses and become self-employed, whereas they had been working in unskilled positions in others' businesses or as farmers before their migration.[27]

Notable individuals

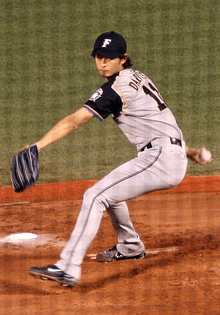

- Yu Darvish, professional baseball player

- Aria Jasuru Hasegawa, professional football player

- Shirin Nezammafi, Japanese language novelist

- May J., J-pop singer

- Sahel Rosa, model, television personality and actress

References

Notes

- Sakurai 2003, p. 19

- Sakurai 2003, p. 33

- Sakurai 2003, p. 41

- Sarah M. Nelson, (1993, pp. 243–258)

- Kidder, J. Edward (1964). Early Japanese Art: The Great Tombs and Treasures. D Van Nostrand Company Inc. p. 105.

- Gary L. Ebersole, “The Religio-Aesthetic Complexes in Manyoushuu Poetry, with Special Reference to Hitomaro’s Aki-no-no Sequence,” History of Religions, 23:1 (August 1983):18–36, pp. 28–33; Ebersole (p. 34)

- ""Research uncovers evidence that ancient Japan was 'more cosmopolitan' than previously thought"". The Japan Times. 2013-05-10. Retrieved 2019-06-01.

- "Paji"; Persian influence in ancient Japan?; CM of the week: Nissin Foods | The Japan Times". The Japan Times. Retrieved 2017-09-12.

- "New Discovery About Persians in Ancient Japan Generates Excitement". 2016-10-10. Retrieved 2019-06-01.

- "Ancient Japan "more cosmopolitan" than thought: researchers". Phys.org. 2016-10-05. Retrieved 2017-10-07.

- ""Paji"; Persian influence in ancient Japan?; CM of the week: Nissin Foods | The Japan Times". The Japan Times. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- "New Discovery About Persians in Ancient Japan Generates Excitement". 2016-10-10. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- Nagashima 1996, p. 389

- Morita 1994 p. 161

- Sakurai 2003, pp. 87–89

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs 1992, III.6.2.4

- Morita 2003, p. 160

- Higuchi 2007, pp. 2–3

- Sakurai 2003, p. 45

- Sakurai 2003, p. 43

- Higuchi 2007, pp. 6–7

- Mousavi 1996

- Morita 2003, pp. 161–162

- Sakurai 2003, pp. 155–159

- Higuchi 2007, p. 4

- Higuchi 2007, pp. 7–8

- Higuchi 2007, p. 9

Sources

- Higuchi, Naoto (May 2007), "Do Transnational Migrants Transplant Social Networks? Remittances, Investments, and Social Mobility Among Bangladeshi and Iranian Returnees from Japan", 8th Asia Pacific Migration Research Network Conference (PDF), UNESCO, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-11, retrieved 2007-08-07

- Morita, Kiriro; Saskia, Sassen (1994), "The New Illegal Immigration in Japan, 1980-1992", The International Migration Review, 28 (1): 153–163, doi:10.2307/2547030, JSTOR 2547030

- Morita, Toyoko (2003), "Iranian immigrant workers in Japan and their networks", in Goodman, Roger (ed.), Global Japan: The Experience of Japan's New Immigrant and Overseas Communities, Routledge, pp. 159–164, ISBN 0-415-29741-9

- Mousavi, Morteza (September 1996), "Iranians in Japan", The Iranian, retrieved 2007-07-19

- Nagashima, Hiromu (1996), "Persian Muslim Merchants in Thailand and their Activities in the 17th Century: Especially on their Visits to Japan" (PDF), 『長崎県立大学論集』, 30 (3): 387–399

- Sakurai, Keiko (July 2003), 日本のムスリム社会 [Japan's Muslim Societies], Chikuma Shobō, ISBN 4-480-06120-7

- Diplomatic Bluebook: Japan's Diplomatic Activities, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan, 1992, archived from the original on 2007-09-28, retrieved 2007-07-19

Further reading

- Shin'ichi, Kura (1993), 在日イラン人 : 景気後退下における生活と就労 [Iranians in Japan: Life and employment-seeking during the economic recession], Tsukuba University, OCLC 36355911

- Nishiyama, Tsuyoshi (December 1994), 東京のキャバブのけむ [Tokyo Kebab Smoke], Keishobō, ISBN 978-4-7705-9012-1

- Kura, Shin'ichi (April 1996), 景気後退下における在日イラン人 [Iranians in Japan under the economic recession], in Komai, Hiroshi (ed.), 日本のエスニック社会 [Japan's ethnic societies], Akashi Shoten, pp. 229–252, ISBN 978-4-7503-0790-9

- Okada, Emiko (May 1998), 隣りのイラン人 [Our Iranian neighbours], Heibonsha, ISBN 978-4-582-82424-7

- Chiba, Naoki (2001), Iranians in the United States and Japan: self-imagery and individual-collective dynamics, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana, OCLC 52484411