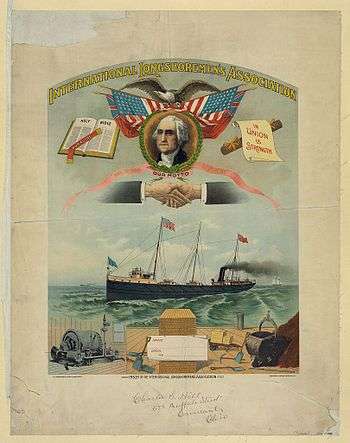

International Longshoremen's Association

The International Longshoremen's Association (ILA) is a labor union representing longshore workers along the East Coast of the United States and Canada, the Gulf Coast, the Great Lakes, Puerto Rico, and inland waterways. The ILA has approximately 200 local affiliates in port cities in these areas.

| |

| Full name | International Longshoremen's Association |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1892 |

| Members | 65,000 (2010) |

| Affiliation | AFL-CIO, CLC, ITF |

| Key people | Harold J. Daggett., President |

| Office location | North Bergen, New Jersey[1] |

| Country | United States, Canada |

| Website | www.ilaunion.org |

Origins

The roots of the International Longshoremen's Association date to colonial America when the arrival of ships bearing goods from Europe was greeted with cries for "Men ‘long shore!" At first, the "longshoremen" who came to the ships were normally engaged in any number of full-time occupations, but left their work freely to unload the anxiously awaited and sometimes desperately needed supplies without compensation. As America began to develop a fledgling economy, and the ships increased, longshore work became a full-time occupation.

As the nation matured, many new immigrants congregated in the cities, hoping to find work, especially along the coast, where the bulk of business was still being done. The number of professional longshoremen grew by thousands.

By the early 19th century, the longshoreman of the day eked out a meager existence along the North Atlantic coast. Their working conditions were wretched and their wages pitiful. Many were new to the country and unfamiliar with the customs and language. Exploitation was the order of the day.

Thus, by mid-century, the longshoremen had begun to organize. In 1864, the first modern longshoremen's union was formed in the port of New York. It was called the Longshoremen's Union Protective Association (LUPA).

While longshoremen in the United States had organized and conducted strikes before there was a United States, the ILA traces its origins to a union of longshoremen on the Great Lakes: the Association of Lumber Handlers founded in 1877, then renamed the National Longshoremen's Association of the United States, in 1892. It joined the American Federation of Labor in 1895 and renamed itself the International Longshoremen's Association several years later, when it admitted Canadian longshoremen to membership.

Organized and led by an Irish tugboat worker named Daniel Keefe, the organization had as many as 100,000 members on the Great Lakes, the East Coast, the West Coast and the Gulf Coast in 1905. From the outset, Keefe faced significant challenges, most notably the outright hostility to unions of Chicago's influential industrialists and the traditional anti-union leanings of longshore recruits from small Midwestern towns. Nevertheless, Keefe successfully expanded membership in the newborn union to include large numbers of dockworkers.

The late 19th century was a time of great economic upheaval which saw periods of almost full employment and union expansion followed by depression, lower wages, and intense competition for jobs. There were bitter divisions among the Irish immigrants and their "non-white" counterparts ("non-white" is the derogatory term then used to refer to Italian and Southern Mediterranean immigrants). These divisions were to some extent exacerbated and often exploited by business interests seeking to turn the unions against themselves. Various unions, such as LUPA and the Knights of Labor, competed with one another, and weak labor leadership was unable to resist increasingly powerful business interests.

Unions were broken. LUPA was disbanded before the start of the 20th century. But other labor unions fought back. There were countless wildcat and/or organized work stoppages resulting in violence and massive losses in wages. Between 1881 and 1905 there were more than 30,000 strikes.

In 1892, delegates from eleven ports convened in Detroit where they adopted the by-laws of the Longshoremen's Chicago local and the name National Longshoremen's Association of The United States. By 1895, the name was changed to International Longshoremen's Association to reflect the growing numbers of Canadian members. Shortly thereafter, the ILA affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL).

As the start of the 20th century loomed, the ILA had approximately 50,000 members, almost all on the Great Lakes. By 1905, membership had doubled to 100,000, half of which were scattered throughout the rest of the country. ILA leaders focused on eliminating independent stevedoring firms and securing closed shop contracts. Keefe bargained with employers, guaranteeing uninterrupted work in return for badly needed improvements in working conditions and wage increases.

Daniel Keefe retired as President of the ILA in 1908, succeeded by another Great Lakes tugboat man, T.V. O'Connor. O'Connor's presidency spanned twelve of the ILA's most intriguing and influential years. In 1909, a bitter three-year strike on the Great Lakes pitted the employers' Lake Carriers' Association against every maritime union except the ILA, whose locals wisely voted against participation because it was clear to them from the beginning that the strike was a losing battle. So powerful and well equipped was the Lake Carriers' Association that Lakes shipping ran almost regularly despite the union walk out. In the end, the ILA was almost alone on the Lakes.

For longshoremen nationwide, and especially for those in the Port of New York, this was an era of great contradiction, where landmark legal advances to protect the rights and safety of workers stood in stark contrast to the actual conditions for longshoremen. The United States was the only country with a large foreign commerce without any laws to protect the safety of its longshoremen. Even the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914, which legalized strikes, boycotts, and peaceful picketing did little to improve actual working conditions for longshoremen.

The 1914 absorption of LUPA into the ILA prompted the creation of the ILA's New York District Council and ignited an intense period of growth for the union both in terms of size and power. The organization of coastwise longshoremen in 1916 was a significant victory that greatly improved the ILA's position at bargaining tables: shippers no longer had the option of diverting freight from striking ports along the Atlantic.

As the ILA grew, power shifted increasingly to the Port of New York, where the branch headquarters for the International were established. There, a man named Joseph Ryan was organizing longshoremen as an officer of the ILA's New York District Council and in 1918, president of the ILA's "Atlantic Coast District."

In 1921, ILA president T.V. O'Connor resigned. Anthony Chlopek, the last of the Great Lakes presidents, was elected ILA International president and Ryan served as his First Vice president for the six years of Chlopek's presidency. Perhaps the most significant development during Chlopek's term was the institution of the Prohibition Enforcement Law. In direct contrast to its desired effect, Prohibition actually had a demoralizing, corrupting effect on society.

The ILA faced competition, particularly from the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), which had a number of members on the West Coast, where many workers moved into longshoring from other centers of IWW strength, such as the lumber and mining industries, and in Philadelphia, where the IWW remained a force after the prosecution and conviction of many of its leaders in 1919 largely destroyed the organization. The ILA survived, even after an open shop campaign on the West Coast and a failed strike in New York City in 1919 left it much weakened.

Joseph Ryan was elected International president in 1927. During the Great Depression, masses of unemployed workers flooded the market with cheap labor and company unions flourished. Then, encouraged by passage of New Deal legislation limiting the use of injunctions to prevent strikes and picketing (the Norris – La Guardia Act) and guaranteeing the rights of workers to vote for their own representation (Wagner Act of 1935), the union immediately began reorganizing and reclaiming lost ports.

Ryan and the union's regional and local leaders regained much of the lost ground, but often at the cost of diminished centralization. Nonetheless, membership again soared, increasing as much as sixfold in as many years in some districts. But the process of rebuilding was not without hurdles. After the largely successful 83-day 1934 West Coast longshore strike, Pacific coast longshoremen voted to secede from the ILA and joined the Congress of Industrial Organizations as the International Longshore and Warehouse Union.

In the history of the ILA, the port of Baltimore, which was a sixth largest port in the world around the start of the 20th century, had a unique impact on the legacy of the Longshoremen's Union. Unlike the Port of New York or Boston which were dominated by Irish and German immigrants, Baltimore's stevedores and longshoremen were overwhelmingly Polish. In the 1930s about eighty percent of the Baltimore's longshoremen were Polish or of Polish descent.[2] The port of Baltimore had an international reputation of fast cargo handling credited to the well-organized gang system that was nearly free of corruption, wildcat strikes and constant work stoppages unlike its other East coast counterparts. In fact, the New York Anti-Crime Commission and the Waterfront Commission of New York looked upon the Baltimore system as the ideal one for all ports.The hiring of longshoremen in Baltimore by the gang system dates back to 1913, when the ILA was first formed. The Polish longshoremen began setting up the system by selecting the most skilled men to lead them. This newly formed gang would usually work for the same company, which would give the priority to the gang. During the times where there was no work within the particular company, the gang would work elsewhere, or even divide to aid other groups in their work, which would speed up the work and would make it more efficient.[3] In an environment as dangerous as a busy waterfront, the Baltimore's gangs always operated together as a unit, because the experience let them know what each member would do at any given time making a water front a much safer place.[4] At the beginning of the Second World War Polish predominance in the Port of Baltimore would significantly diminish as many Poles left to fight the war.

The spirit of rebirth continued as World War II created a commercial boom. Following the war, the ILA was at its peak, with wages and membership up. Ryan was elected "Lifetime President," an honorary title reflecting his stature and prominence in the union. Unfortunately for Ryan and the ILA, the union's toughest battle loomed in the near future.

Secession of the West Coast locals

The ILA Pacific Coast District was led by the radical left-winger Harry Bridges, who rebelled against Ryan's leadership during the 1934 West Coast longshore strike. A network of union activists largely circumvented Ryan during the strike, first organizing the membership to reject the contract that Ryan had negotiated, then leading a strike over his objections. Bridges and other veterans of the strike replaced Ryan loyalists in union elections up and down the West Coast following the strike.

Ryan never trusted Bridges, even though he was forced to make him an International officer in recognition of his de facto power on the West Coast. Ryan fired Bridges in 1936, however, after Bridges launched an East Coast speaking tour in support of the left-wing sailors' union, the National Maritime Union, with which Ryan had unfriendly relations. Bridges subsequently took all but three of the ILA's West Coast locals out of the ILA to form the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, which joined the Congress of Industrial Organizations shortly thereafter.

Allegations of organized crime

Longshoremen obtained work through a shapeup in which bosses chose a workforce on a daily basis. Longshoremen often worked only a day or less per week as a consequence. Work was especially uncertain for those who unloaded trucks and had to appeal to gangsters who controlled this work for employment.

The 1950s was a decade of turmoil and trauma for the ILA. Several sensationalist articles printed in New York City newspapers focused on alleged rampant gangsterism on the City's waterfront. The movie On the Waterfront would later popularize this viewpoint. At the same time, increasing unrest on the New York waterfront caused by internal conflicts in the ILA resulted in a 25-day work stoppage that halted only when New York State Industrial Commissioner Edward Corsi appointed a board of inquiry to investigate the October 1951 agreement in question. Extending the investigation beyond its original mandate, the Corsi Report first addressed the voting procedures initially at question—which turned out to be flawed, but not fraudulent—and then went on to focus on irregularities in the administration of several New York locals.

The Corsi Report captured the attention of the public. It was perfect ammunition for the press—as well as that of Governor Thomas E. Dewey, who ordered his New York State Crime Commission to conduct a full investigation of the ILA. In actuality, the investigation was more like a trial, with "witnesses" testifying against the ILA and its leadership. Eventually, the highly publicized investigation ended with the condemnation of both the ILA and Joseph Ryan as corrupt. The Waterfront Commission of New York Harbor was created in 1953 to temporarily oversee the waterfront.

The ILA strove to clean house and rid itself of the few members who had in fact been proven corrupt or criminal. In August 1953, the ILA was suspended from the American Federation of Labor (AFL), a devastating blow. The AFL created the International Brotherhood of Longshoremen (IBL-AFL) to replace the besmirched ILA and scheduled representational elections.

The accusations of negligence which so brutally damaged Ryan's reputation were ultimately proved to be groundless. Nevertheless, under the relentless pressure of the investigations and denunciations, Ryan resigned. Captain William V. Bradley was elected to the presidency of the ILA-Independent at the November 1953 convention.

Rivalry with the IBL

To combat the spread of the IBL (International Brotherhood of Longshoremen), the ILA sent Thomas "Teddy" Gleason, ILA General Organizer, from port to port nationwide. Meanwhile, 17,000 longshoremen voted in the 1953 National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) election[5] to determine representation in the Port of New York. The ILA was victorious, but immediately, Governor Dewey waged a campaign to overturn the election results.

Tension on the New York piers was mounting. ILA loyalists and many other longshoremen were at best suspicious of the IBL, which they viewed as a machine of the Waterfront Commission and a scab union—an organization of workers perceived as having a role in strike breaking. By early March 1954, the storm finally hit when Teamster boss David Beck was perceived as betraying the ILA by refusing to cross an IBL picket line. News spread and on piers up and down Manhattan, ILA longshoremen refused to touch Teamster deliveries. Gangs of longshoremen walked off the docks in a wildcat strike.

An NLRB injunction forbade ILA leaders from striking or disrupting freight transportation. Violence erupted as the IBL, facilitated by the police and Beck's Teamsters, smashed picket lines. Then the NLRB examiner effectively overturned the December elections. This proved to be the last straw, for less than a week later, Bradley made the ILA strike official. Other unions and workers gave their complete support to the ILA, including a major Teamsters local, which indicated Beck's opposition to the ILA strikers was not shared throughout the rest of the Teamsters.

The balance of power began to shift as Gleason gained ground against the IBL and longshoremen along the coast refused to handle diverted cargo. Dewey's anti-ILA entourage responded to the shift with a series of legal actions. Then, the NLRB officially set aside the results of the December elections and called for a new vote. The final blow, however, was the NLRB's announcement that the ILA would be banned from future elections unless it ended the work stoppage "forthwith". Bradley had no choice but to send his men back to work.

The ILA won a slim victory in the May 26, 1954, election, despite aggressive IBL campaigning. In August 1954, the results were finally approved and certified by NLRB and the ILA was given representational rights in the Port of New York. The IBL did not go quietly and forced a third representational election in 1956, in which it was again defeated. By the time an AFL-CIO committee recommended re-admittance for the ILA in August 1959, the IBL was active only in the Great Lakes. In October, the IBL officially dissolved itself and IBL president Larry Long became president of ILA's Great Lakes District.

Teddy Gleason was unanimously elected president at the ILA International Convention in 1963. He had always been respected, and the value of his efforts as General Organizer during the troubles of the 1950s was well known. The delegates who elected Gleason were looking for change, progress, and modernization. Gleason took up this charge and moved the headquarters to its current focused on settling the union's troubled financial affairs.

Containerization

In 1965, Gleason negotiated what was at the time, the longest lasting ILA contract in history. It was also the first truly forward-looking contract the union signed. As automation and containerization increased, the contract focused on preserving jobs. Gleason-era initiatives such as the Guaranteed Annual Income (GAI) program, the Job Security Program (JSP). Under Gleason, the ILA once again became a strong and powerful force in the world of labor.

Some employers outside New York who faced the loss of business as a result of the agreement challenged the "Rules on Containers" that were negotiated and agreed to by management and labor as a means of preserving jobs. The National Labor Relations Board originally upheld the challenge, only to be reversed by the United States Supreme Court in two cases in the 1980s that found that the rules were lawful and did not violate federal labor law.

Ironically, however, the Rules on Containers were subsequently eviscerated by the Federal Trade Commission, which found that the Rules were an impermissible restraint on trade.

Governmental oversight

In 1953 the states of New York and New Jersey entered into an interstate compact, with Congressional approval, that established a Waterfront Commission responsible for regulating the ILA by preventing individuals with a criminal record from holding positions within it. The Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act, passed in 1959, imposed similar restrictions on all private sector unions.

Political activities

Like the ILWU, which conducted symbolic strikes in which it refused to handle goods going to fascist states in the 1930s or from apartheid-era South Africa in the 1980s, the ILA conducted similar boycotts aimed at trade with the Soviet Union during periods of crisis, such as the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. The Supreme Court ruled in two companion cases in the 1980s that the union's boycott could not be enjoined under the Norris-LaGuardia Act, but that it was an unlawful secondary boycott that could be outlawed on that basis under the Taft-Hartley Act.

See also

- Anthony Anastasio

- Anthony "Sonny" Ciccone

- Danny Greene

- New York City tugboat strike of 1946

- Paul Kelly (early twentieth-century gangster active in 1919 strike)

- Pete Panto

- Industrial Workers of the World (Wobblies)

- Anthony Scotto (politically connected captain in the Gambino crime family for more than a decade who was also a key officer in the I.L.A.)

- On the Waterfront (film set in Hoboken, New Jersey in the early 1950s)

- Longshoremen v. Allied Int'l, Inc. 1982 US Supreme Court case which held ILA's boycott of handling Soviet cargo was an unfair labor practice

References

External links

- History of the 1948 Strike by Colin J. Davis

- History of the Great Lakes ILA

- Article reviewing history of efforts to outlaw union corruption

- ILA News

- Commentary on the Charleston Five case

Archives

- Ronald Magden Papers. 1879-2003. 28.27 cubic feet (34 boxes). At the Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Libraries Special Collections. Contains materials collected by Ronald Magden on the International Longshoremen's Association.

- John Gallacci Papers. 1933-1956. 0.03 cubic feet (1 vertical file).

Further reading

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-04-03. Retrieved 2012-12-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Hollowak, Thomas L. A History of Polish Longshoremen and Their Role in the Establishment of a Union at the Port of Baltimore. Baltimore: History Press, 1996.

- Delich, Helen.Noted for Fast, Efficient Work Baltimore System of Operating is Termed Ideal for All Ports. Baltimore Sun, 1955.

- Delich, Helen.Ganging Up on the Water Front. Baltimore Sun, 1954.

- The elections took place on 24 and 25 December 1953.

- Kimeldorf, Howard, Reds or Rackets, The Making of Radical and Conservative Unions on the Waterfront, ISBN 0-520-07886-1