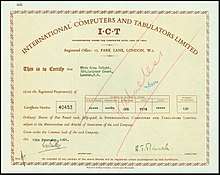

International Computers and Tabulators

International Computers and Tabulators or ICT was formed in 1959 by a merger of the British Tabulating Machine Company (BTM) and Powers-Samas. In 1963 it also added the business computer divisions of Ferranti. It exported computers to many countries around the world and went on to become part of International Computers Limited (ICL).

.jpg)

Products

The ICT 1101 was known as the EMIDEC 1100 computer before the acquisition of the EMI Computing Services Division who designed and produced it.

The ICT 1201 computer used thermionic valve technology and its main memory was drum storage. Input was from 80-column punched cards and output was to 80-column cards and a printer. Before the merger, under BTM, this had been known as the HEC4 (Hollerith Electronic Computer, fourth version).

The drum memory held 1K of 40-bit words. The computer was programmed using binary machine code instructions. When programming the 1201, the machine code instructions were not sequential but were spaced to allow for the drum's rotation. This ensured the next instruction was passing under the drum's read heads just as the current instruction had been executed.

The ICT 1301, and its smaller cousin the ICT 1300, used germanium transistors and core memory. Backing store was magnetic drum, and optionally one-inch-, half-inch- or quarter-inch-wide magnetic tape. Input was from 80-column punched cards and optionally 160-column punched cards and punched paper tape. Output was to 80-column punched cards, printer and optionally to punched paper tape. The first customer delivery was in 1962, a 1301 sold to the University of London. One of their main attractions was that they performed British currency calculations (pounds, shillings and pence) in hardware. They also had the advantage of programmers not having to learn binary or octal arithmetic as the instruction set was pure decimal and the arithmetic unit had no binary mode, only decimal or pounds, shillings and pence. Its clock ran at 1 MHz. The London University machine still exists (January 2006) and is being reinstated to working condition by a group of enthusiasts.

The ICT 1302, used similar technology to the 1300/1301 but was a multiprogramming system capable of running three programs in addition to the Executive. It also used the 'Standard Interface' for the connection of peripherals allowing much more flexibility in peripheral configuration. The 'Standard Interface' was originally prototyped on the 1301 and went on to be used on the 1900 series.

The ICT 1400 was a first generation computer using thermionic valves, but was overtaken by transistor technology in 1959 and no sales were made.[1]

The ICT 1500 series was a design bought in from the RCA Corporation, who called it the RCA 301. RCA also sold the design to Siemens in Germany and Compagnie des Machines Bull in France who called it the Gamma 30. It used a six-bit byte and had core stores of 10,000, 20,000 or 40,000 bytes.

The ICT 1900 series was devised after the acquisition of Ferranti's assets which brought in the new Ferranti-Packard 6000 machine from Ferranti's Canadian subsidiary, which was considerably more advanced than the existing 130x line. It was decided to adapt this machine to use the 'Standard Interface', and it was put on the market as the ICT 1904, the first in a range of upward-compatible computer systems.

In 1968 ICT merged with English Electric Computers, itself formed from the prior mergers of English Electric Leo Marconi (EELM) and Elliott Automation. The resulting company became International Computers Limited (ICL). At the time of the merger English Electric Computers was in the process of making a line of large IBM System/360-compatible mainframes based on the RCA Spectra 70, which was sold as the ICL System-4. Both 1900 and System-4 were eventually replaced by the ICL 2900 Series which was introduced in 1974.

External links

- Oral history interview with Arthur L. C. Humphreys, Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota. Humphreys, a former managing director of ICL, reviews the history of the British computer industry, including the merger in 1959 of British Tabulating Machine Company and the Powers Samas company into International Computers and Tabulators, Ltd. (ICT), and the merger in 1968 of English Electric Computers Limited and ICT into ICL.

- Boards from the ICT 1301

- ICT 1301 Resurrection Project

- Two articles on the HEC4 at Morgan Crucible Co

References

- Johnson, Roger (2008), School of computer science and information systems: A short history (PDF), 50 years of Computing, UK: Birkbeck School of Computing.