Institut für Sexualwissenschaft

The Institut für Sexualwissenschaft was an early private sexology research institute in Germany from 1919 to 1933. The name is variously translated as Institute of Sex Research, Institute of Sexology, Institute for Sexology or Institute for the Science of Sexuality. The Institute was a non-profit foundation situated in Tiergarten, Berlin. It was headed by Magnus Hirschfeld. Since 1897 he had run the Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee ("Scientific-Humanitarian Committee"), which campaigned on progressive and rational grounds for LGBT rights and tolerance. The Committee published the long-running journal Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen. Hirschfeld built a unique library on same-sex love and eroticism.[1]

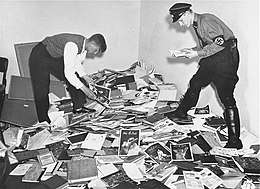

The Nazi book burnings in Berlin included the archives of the Institute. After the Nazis gained control of Germany in the 1930s, the institute and its libraries were destroyed as part of a Nazi government censorship program by youth brigades, who burned its books and documents in the street.[2]

Origins and purpose

.jpg)

The Institute of Sex Research was opened in 1919 by Magnus Hirschfeld and his collaborator Arthur Kronfeld,[3] a once famous psychotherapist and later professor at the Charité. As well as being a research library and housing a large archive, the Institute also included medical, psychological, and ethnological divisions, and a marriage and sex counseling office. The Institute was visited by around 20,000 people each year, and conducted around 1,800 consultations. Poorer visitors were treated for free. In addition, the institute advocated sex education, contraception, the treatment of sexually transmitted diseases, and women's emancipation.

The Institute became a point of scientific and research interest for many scientists of sexuality, as well as scientific, political and social reformers in Germany and Europe, particularly from socialist, liberal and social-democratic circles. In 1923 the Institute was visited by Nikolai Semashko, Commissar for Health in the Soviet Union. This was followed by numerous visits and research trips by health officials, political, sexual and social reformers, and scientific researchers from the Soviet Union interested in the work of Hirschfeld.[4] In 1926 a delegation from the institute, led by Hirschfeld, reciprocated with a research visit to Moscow. In 1929 Hirschfeld presided over the third international congress of the World League for Sexual Reform at Wigmore Hall.[5]

Transgender pioneers

Magnus Hirschfeld coined the term transsexualism,[6] identifying the clinical category which his colleague Harry Benjamin would later develop in the United States. Transgender people were on the staff of the Institute, as well as being among the clients there. Various endocrinologic and surgical services were offered, including the first modern sex reassignment surgeries in the 1930s. Hirschfeld also worked with Berlin's police department to curtail the arrest of cross-dressed individuals, including those suspected of wearing certain clothing in connection with sex work, through the creation of transvestite passes issued on behalf of the Institute to those who had a personal desire to wear clothing associated with a gender other than the one assigned to them at birth.[7][8]

Nazi era

In late February 1933, as the influence of Ernst Röhm weakened, the Nazi Party launched its purge of gay (then known as homophile) clubs in Berlin, outlawed sex publications, and banned organised gay groups.[9] As a consequence, many fled Germany (including, for instance, Erika Mann). In March 1933 the Institute's main administrator, Kurt Hiller, was sent to a concentration camp. The buildings were later taken over by the Nazis for their own purposes. They were a bombed-out ruin by 1944, and were demolished sometime in the mid-1950s. Hirschfeld tried, in vain, to re-establish his Institute in Paris, but he died in France in 1935.

On 6 May 1933, while Hirschfeld was in Ascona, Switzerland, the Deutsche Studentenschaft made an organised attack on the Institute of Sex Research. A few days later, the Institute's library and archives were publicly hauled out and burned in the streets of the Opernplatz. Around 20,000 books and journals, and 5,000 images, were destroyed. Also seized were the Institute's extensive lists of names and addresses. In the midst of the burning, Joseph Goebbels gave a political speech to a crowd of around 40,000 people. The leaders of the Deutsche Studentenschaft also proclaimed their own Feuersprüche (fire decrees). Also books by Jewish writers, and pacifists such as Erich Maria Remarque, were removed from local public libraries and the Humboldt University, and were burned.[10]

While many fled into exile, the radical activist Adolf Brand made a stand in Germany for five months after the book burnings, but in November 1933 he was forced to announce the formal end of the organised homosexual emancipation movement in Germany. On 28 June 1934 Hitler conducted a purge of gay men in the ranks of the SA wing of the Nazis, which involved murdering them in the Night of the Long Knives. This was then followed by stricter laws on homosexuality and the round-up of gay men. The address lists seized from the Institute are believed to have aided Hitler in these actions. Many tens of thousands of arrestees found themselves, ultimately, in slave-labour or death camps. Karl Giese committed suicide in 1938 when the Germans invaded Czechoslovakia and his heir, lawyer Karl Fein, was murdered in 1942 during deportation.

After World War II

The charter of the institute had specified that in the event of dissolution, any assets of the Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld Foundation (which had sponsored the Institute since 1924) were to be donated to the Humboldt University of Berlin. Hirschfeld also wrote a personal will while in exile in Paris, leaving any remaining assets to his students and heirs Karl Giese and Li Shiu Tong (Tao Li) for the continuation of his work. However, neither stipulation was carried out. The West German courts found that the foundation's dissolution and the seizure of property by the Nazis in 1934 was legal. The West German legislature also retained the Nazi amendments to Paragraph 175, making it impossible for surviving gay men to claim restitution for the destroyed cultural center.[11]

Li Shiu Tong lived in Switzerland and the United States until 1956, but as far as is known, he did not attempt to continue Hirschfeld's work. Some remaining fragments of data from the library were later collected by W. Dorr Legg and ONE, Inc. in the USA in the 1950s.

Later developments

In 1973 a new Institut für Sexualwissenschaft was opened at the University of Frankfurt am Main (director: Volkmar Sigusch), and 1996 at the Humboldt University of Berlin.

References

- Harry Oosterhuis. (Ed.) Homosexuality and Male Bonding in Pre-Nazi Germany: The Youth Movement, the Gay Movement, and Male Bonding Before Hitler's Rise: Original Transcripts from Der Eigene, the First Gay Journal in the World. (1991).

- "Institute of Sexology". qualiafolk.com. Qualia Folk. 8 December 2011. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- In Memory of Arthur Kronfeld)

- Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: The Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent, Dan Healey, 2001, pp.132-133

- The Times, League For Sexual Reform International Congress Opened, 9 September 1929;

- Ekins R., King D. (2001) Pioneers of Transgendering: The Popular Sexology of David O. Cauldwell. IJT 5,2 (text online Archived 2006-04-28 at the Wayback Machine)

- Beachy, Robert (2015). Gay Berlin: Birthplace of a Modern Identity. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 0307473139.

- "Between World Wars, Gay Culture Flourished In Berlin". NPR.org. Retrieved 2017-09-13.

- "The Nazis tolerated gays. Then everything changed". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- Leonidas Hill (2001). "The Nazi Attack on 'Un-German' Literature, 1933-1945" IN: The Holocaust and the Book: Destruction and Preservation.

- James D. Steakley. The Early Homosexual Emancipation Movement in Germany. (1975).

Further reading

- John Lauritsen and David Thorstad. The Early Homosexual Rights Movement, 1864-1935. (Second Edition revised)

- Günter Grau (ed.). Hidden Holocaust? Gay and lesbian persecution in Germany 1933-45. (1995).

- Charlotte Wolff. Magnus Hirschfeld: A Portrait of a Pioneer in Sexology. (1986).

- James D. Steakley. "Anniversary of a Book Burning". The Advocate (Los Angeles), 9 June 1983. Pages 18–19, 57.

- Mark Blasius & Shane Phelan. (Eds.) We Are Everywhere: A Historical Source Book of Gay and Lesbian Politics (See the chapter: "The Emergence of a Gay and Lesbian Political Culture in Germany" by James D. Steakley).

- Beachy, Robert. Gay Berlin: Birthplace of a Modern Identity. (2014)

Film

- Rosa von Praunheim (Dir.) The Einstein of Sex (Germany, 2001). (A biographical drama about Magnus Hirschfeld - English subtitled version available).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Institut für Sexualwissenschaft. |

- "Institute for Sexual Science (1919-1933)" Online exhibition of the Magnus Hirschfeld Society - warning, complex JavaScript and pop-up windows.

- Documentation in the Archive for Sexology, Berlin

- When Books Burn - University of Arizona multimedia exhibit.