Imperial Yeomanry

The Imperial Yeomanry was a volunteer mounted force of the British Army that mainly saw action during the Second Boer War. Created on 2 January 1900, the force was initially recruited from the middle classes and traditional yeomanry sources, but subsequent contingents were more significantly working class in their composition. The existing yeomanry regiments contributed only a small proportion of the total Imperial Yeomanry establishment. In Ireland 120 men were recruited in February 1900.[1] It was officially disbanded in 1908, with individual Yeomanry regiments incorporated into the new Territorial Force.[2]

| Imperial Yeomanry | |

|---|---|

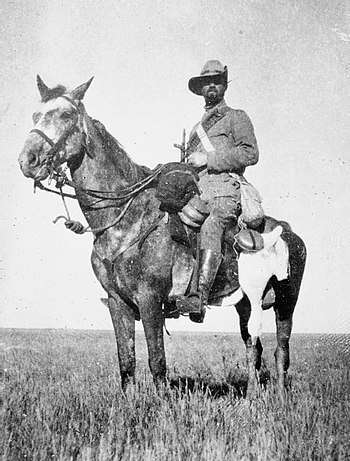

Imperial Yeoman | |

| Active | 1900–1908 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Mounted infantry |

| Size | Regiment |

| Engagements | Second Boer War |

Background

The Dutch Cape Colony was established in modern-day South Africa in the second half of the 17th century. The colony subsequently passed to the Dutch East India Company which, in 1815, sold it to the British, thus strengthening the rival British-ruled Cape Colony. Unhappy with the subsequent British governance, the Dutch settlers, known now as the Boers, established their own territories, the Orange Free State and the Transvaal. The two states were recognised by the British in 1881, following Boer victory in the First Boer War. The discovery of gold in the Transvaal in 1886 led to a gold rush, and the treatment of the prospectors by the Boers resulted in greater British government involvement, a revival of friction between the British and Boers and, in October 1899, the outbreak of the Second Boer War.[3]

Although the Boers were predominantly farmers and were heavily outnumbered by the regular forces of the British Army, they organised themselves into highly mobile mounted columns called commandoes and fought at long range with accurate rifle fire. Their tactics proved to be highly effective against the lumbering British forces, and in one week in December 1899, known as Black Week, they inflicted three significant defeats on the British.[4] It soon became apparent that the British mounted capability – comprising small contingents of regular infantry on horseback and insufficiently supplied, ill-suited cavalry – needed to be reinforced.[5]

The basis for just such reinforcement had been in existence since 1794 in the form of the volunteer Yeomanry Cavalry. Already, in October and November 1899, Lieutenant-Colonel A. G. Lucas, the yeomanry representative in the War Office and a member of the Loyal Suffolk Hussars, had proposed this force as a source of reinforcement. His proposals were initially declined, but the request by General Redvers Buller, Commander-in-Chief of the British forces in South Africa, for mounted infantry after his defeat in the Battle of Colenso on 15 December 1899 prompted a rethink.[6] The domestic yeomanry was, however, a small home defence force, only some 10,000 strong, steeped in a cavalry tradition and restricted by statute to service only in the United Kingdom, making it in itself unsuitable for service in South Africa.[7][8]

Creation

On 18 December, Lords Lonsdale and Chesham, who both commanded yeomanry regiments, offered to recruit 2,300 volunteers from the domestic yeomanry for service in South Africa. Although Lord Wolseley, Commander-in-Chief of the Forces opposed it, George Wyndham, Under-Secretary of State for War and himself a yeoman, established an imperial yeoman committee with Chesham and two other yeomanry commanders. The result, announced on 24 December, was the Imperial Yeomanry, which was duly established on 2 January 1900. By the end of the war, just under 35,000 men were recruited in three separate contingents.[lower-alpha 1] Its structure, companies and battalions rather than the squadrons and regiments of the domestic yeomanry, reflected its role as mounted infantry.[10][11] The existing yeomanry was invited to provide volunteers for the new force, thus forming a relatively trained nucleus on which it was built. It was, however, a distinct body in its own right, separate from the home force, and the domestic yeomanry provided only around 18 per cent of the first contingent of over 10,000 men.[12][13][lower-alpha 2] Volunteers also came from the yeomanry's infantry counterpart, the Volunteer Force, but the majority were newly recruited from the yeomanry's traditional demographics of the middle class and the farming community, although some 30 per cent were working class.[16] The first contingent recruits were able to build on the experience many of them already had with horsemanship and firearms courtesy of two or three months drilling in domestic yeomanry regiments before they were shipped to South Africa.[17][15]

Operations in the Second Boer War

The first contingent of Imperial Yeomanry departed for South Africa between January and April 1900.[18] Its first action came in the Battle of Boshof on 5 April, when its 3rd and 10th Battalions surrounded and defeated a small force of European volunteers and Boers commanded by the Comte de Villebois-Mareuil.[19][20] This success was overshadowed by a disaster the next month which tarnished the Imperial Yeomanry's reputation, when its 13th Battalion was ambushed and surrounded by 2,500 Boers at Lindley on 27 May. The yeomen were besieged for four days before they finally surrendered, losing 80 killed and 530 captured. Among the prisoners were the future Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, James Craig, and four members of the House of Lords.[21][22]

Although the defeat at Lindley reflected poorly on the yeomanry, the yeomen had fought as competently as any regular soldier, and much of the blame lay with poor leadership by Lieutenant-Colonel Basil Spragge, the regular officer commanding the battalion, and the failure of Major-General Henry Colvile to come to the aid of the yeomanry with his Guards Brigade. Questionable leadership featured in another encounter between yeomanry and Boer at the Battle of Nooitgedacht on 13 December. Three companies of yeomanry formed part of a regular brigade commanded by Major-General R. A. P. Clements which was attacked as it camped, by a superior Boer force. Clements was heavily criticised for his poor choice of campsite, though his swift action enabled him to extricate his brigade, albeit with casualties, during which the yeomen demonstrated their ability to operate alongside the regular army in a complex combined operation.[23]

By the end of March 1901, almost 30 per cent of the original 10,000+ Imperial Yeomanry had been killed, injured or taken prisoner, though the majority of losses were caused by disease. The slow demobilisation of the survivors, who were allowed to return home after just one year, and the arrival of a second contingent of over 16,000 new recruits increased the size of the Imperial Yeomanry in-country to over 23,000 by May, though this figure had fallen back to 13,650 by January 1902.[24]

Second contingent

A number of issues conspired against the second contingent. Recruitment, which had ceased after the first contingent had been raised, had to be restarted. The original intention was, as with the first contingent, to train new recruits for two or three months before sending them to South Africa, but the new Commander-in-Chief, Lord Kitchener, decided that they should be trained in-theatre and ordered that they be sent immediately. He failed to appreciate, however, that a pay rise had attracted a significantly greater number of working class recruits who had no prior experience of horses or firearms. Lord Chesham, who in 1901 became the Inspector General of the Imperial Yeomanry, would later state of the second draft that "the shooting and riding test, if it was really applied in all cases, must have been one of very perfunctory character".[25][26] The difficulties of this sudden injection of raw, untrained recruits were compounded by the fact that only 655 of the original contingent elected to stay on, representing a significant loss of experience. Furthermore, the second tranche of domestic yeomanry officers who provided much of the leadership were not vetted by domestic yeomanry commanders as those few of the first contingent were, and proved to be of poor quality in the field.[27][lower-alpha 3]

The second contingent saw its first action at Vlakfontein on 29 May 1901, when four companies of Imperial Yeomanry were, along with a company of regular infantry and two guns of the Royal Artillery, part of a rear guard commanded by Brigadier-General H. G. Dixon. An attack by 1,500 Boers caused a significant portion of the yeomanry to break and fall back on the infantry, causing confusion and casualties, before a counter-attack by the infantry and one company of yeomanry forced the Boers to retire. Although only one 200-strong company of yeomanry was involved in the counter-attack, suffering nine casualties, the yeomanry suffered in total 30 per cent casualties, while the regular infantry suffered very heavily, losing 87 out of an estimated strength of 100.[29]

The yeomanry's inexperience in defence and convoy protection was repeatedly exposed in Boer attacks. At Moedwil (also known as Rustenburg) on 30 September, the Boers inflicted nearly twice as many casualties as they sustained and killed or wounded all of the yeomanry's horses.[30][31] In the Battle of Groenkop (also known as Tweefontein) on 25 December, 1,000 Boers surprised and practically annihilated the 400-strong 11th Battalion as the men slept, inflicting casualties of 289 killed, wounded and captured, for the loss of 14 killed and 30 wounded.[32] At Yzerspruit on 25 February, a convoy escorted by 230 men of the yeomanry 5th Battalion and 225 regular infantry of the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers was attacked by a 1,500-strong Boer force. The British beat back four charges before surrendering with the loss of 187 men killed or wounded, 62 of them yeomen, 170 horses, several hundred rifles and half a million rounds of ammunition, for the loss to the Boers of 51 men killed or wounded.[33] In the Battle of Tweebosch on 7 March, a British column of 1,300 men, 300 of them Imperial Yeomanry, led by Lieutenant-General Paul Methuen, suffered 189 killed or wounded and 600 taken prisoner, Methuen among them. It was considered to be one of the most embarrassing defeats of the war, the blame for which was placed on the yeomanry; the 86th (Rough Riders) Company, a raw draft only recently sent to South Africa, lacked leadership, according to Methuen, and were "very much out of hand, lacking both fire-discipline and knowledge of how to act", and the 5th Battalion broke in the face of the Boer aggression, leading to the capture of the artillery and surrender of the column.[34][35]

Third contingent

At the end of 1901, a third contingent of over 7,000 Imperial Yeomanry was raised. Having learned from the failures of the previous draft, these men underwent three months of thorough training in the UK, during which time sub-standard officers and men were weeded out, before being sent to South Africa, and a number of regular army officers were allocated to lead them. Representing the best prepared Imperial Yeomanry contingent, it arrived just as the war was ending, and saw only limited involvement.[36]

Performance

General Edmund Allenby, who would rely on yeomanry regiments when he commanded the Egyptian Expeditionary Force in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of the First World War, regarded the Imperial Yeomanry as useless. By the time they had learned enough to be of use, according to him, they had "probably been captured two or three times, presenting the Boers on each occasion with a horse, rifle and 150 rounds of ammunition per man".[37] The colonial forces in South Africa had labelled the second contingent "De Wet's Own", after the Boer general Christiaan de Wet, so invaluable was it as a source of rifles and horses to the Boers.[38] Questions were asked about the second contingent in the House of Commons, it began to be derided in the press, and in July 1901 Kitchener considered sending it back.[39]

A month later, Kitchener had relented a little, saying that although there were still some who could not be trusted, a good many of the sub-standard yeomanry had been removed and he was getting more value from the best of those remaining. Methuen blamed a lack of preparation and training for the yeomanry's poor performance, and later stated that, having gained experience during the campaign, he would "place implicit reliance in them after a short time". After seven months as commander of the Imperial Yeomanry, Major-General Reginald Brabazon also underlined the acquisition of experience when he wrote that it was "as valuable a corps of fighting men as ever wore the Queen's uniform".[39][40] That the Imperial Yeomanry did on occasion perform well was exemplified by the action at Rustenburg where, although caught napping and losing the only column operating in the area at the time, the yeomen had fought as well as the regular infantry, and the 74th (Dublin) Company earned high praise for its conduct in beating off an attack on a convoy at Rooikopjes on 24 August.[41][35]

The Imperial Yeomanry suffered 3771 casualties in the war, compared to the regular cavalry's 3623. Of all the auxiliary forces that saw action in South Africa, the yeomanry took the brunt of the fighting; more than 50 per cent of its casualties were a result of enemy action, compared to 24 per cent for the militia and 21 per cent for the Volunteer Force.[42] Those imperial yeomen recruited from the domestic yeomanry returned to their home regiments, endowing them with their first battle honour, "South Africa 1900–01".[43]

After the war

The gulf between domestic and imperial yeomanries is apparent from the fact that the former accepted only 390 new recruits from the latter after the war.[44] By 1900, the domestic yeomanry establishment had stood at just over 12,000 while its actual strength was some 2,000 short of that figure.[45] Although the force had been maintained for its utility as mounted police in aid of the authorities in times of civil unrest, this role had all but disappeared in the second half of the 19th century. The yeomanry failed to adapt, remaining wedded to its original military role of light or auxiliary cavalry and resolutely opposing moves in 1870 and 1882 to convert it to a mounted infantry role.[46] By the end of the 19th century, the domestic yeomanry was militarily weak, largely unchanged since its formation over a century previously, of questionable benefit and no clear purpose.[47] The experiences in South Africa suddenly made the force relevant again, not only for the wave of enthusiasm that saw its numbers double, nor the relatively small role the domestic yeomanry played in the Imperial Yeomanry, but in the clear indication of the necessity of mounted infantry over traditional cavalry. This was identified by the Harris Committee – chaired by the former Assistant Adjutant general of the Imperial Yeomanry, Lord Harris, and comprising six yeomanry officers and a regular cavalry officer, convened to advise on the future organisation, arms and equipment of the domestic yeomanry – and informed the Militia and Yeomanry Act of 1901.[48]

The new legislation renamed the domestic yeomanry en bloc to "Imperial Yeomanry" and converted it from cavalry into mounted infantry, replacing its primary weapon, the sword, with rifle and bayonet. It introduced khaki uniforms, mandated a standard four-squadron organisation and added a machine-gun section to each regiment. The yeomanry's establishment was set at 35,000, though effective strength was only around 25,000, and to achieve these numbers, 18 new regiments were raised, 12 of them resurrected from disbanded 19th century corps of yeomanry.[49][50] The Harris Committee was not unanimous, and it was in fact a minority report by just two officers that recommended the removal of "cavalry" from the yeomanry's title (it being generally referred to as "Yeomanry Cavalry" before the rename) and the retirement of the sword. The yeomanry resisted these changes. Three regiments petitioned the king to be allowed to retain the sword on parade, and all but one of the 35 commanding officers petitioned the army for its retention in 1902.[51][lower-alpha 4]

As well as issues with the domestic yeomanry, the Boer War also exposed the wider problem of reinforcing the army with sufficiently trained men in times of need.[53] This occupied much of the debate concerning military reform in the first decade of the 20th century, and gave the yeomanry the opportunity to retain its treasured role as cavalry by positioning itself as a semi-trained reserve to the numerically weak regular cavalry. This was reflected in a change to the training instructions issued to the Imperial Yeomanry in 1902 and 1905. The former warned the yeomanry not to aspire to a cavalry role and made no distinction between yeomen and mounted infantry, but the latter merely proscribed the traditional cavalry tactic of shock action while otherwise aligning the yeomanry with the cavalry, giving it in effect the role of dismounted cavalry.[54]

The changed focus in training was prompted by plans to allocate six yeomanry regiments as divisional cavalry in the regular army, supported by the establishment within the Imperial Yeomanry of a separate class of yeoman free of the restriction on service overseas.[55] This, however, relied on men volunteering for such service, and offered the regular army no guarantee that enough men would do so. That enough would volunteer was made more doubtful by the requirement that they should abandon their civilian lives for the six months of training considered necessary for them to be effective in such a reserve role. As a result, the plans were dropped from the final legislation that combined the Volunteer Force and the yeomanry, now without the "Imperial" prefix, into a single, unified auxiliary organisation, the Territorial Force, in 1908.[56][lower-alpha 5][lower-alpha 6]

Footnotes

- According to Leo Amery's The Times History of the War in South Africa, 35,520 Imperial Yeomanry went to South Africa. Of this number probably 2,000 at least went out a second time and so have been counted twice over. After 29 October 1901, when it was made permissible, a certain number of Imperial Yeomanry enlistments took place in South Africa, and 833 officers and men were recruited under Imperial Yeomanry conditions for a corps raised partly in South Africa and partly at home.[9]

- Hay reports a first contingent strength of 10,371 men, of which 18.3 per cent were recruited from the domestic yeomanry, and states that no known figure exists for the number of officers. Athawes gives a figure of 550 officers and 10,571 other ranks.[14][15]

- Most of the first contingent officers were not sourced from the domestic yeomanry. Nearly 60 regular officers had to be borrowed from regular units, though the source is not clear over what time period. Of the domestic yeomanry officer corps who served in South Africa, the subalterns performed well once they gained experience, but squadron commanders and colonels were "...out of their depth on occasion, and at times simply not up to the commands allocated".[28]

- Colonel Lancelot Rolleston, commander of the South Nottinghamshire Imperial Yeomanry, went further and refused to surrender the regiment's swords on the grounds that the regulations permitted their use until the equipment was worn out, and even introduced the lance to the regiment in 1904. With some string-pulling, the regiment secured for itself a place in the Northern Command review in 1903, in which it drilled alongside the regular forces as cavalry and paraded without rifles.[52]

- The difficulties inherent in relying on volunteers to reliably augment the regular army can be seen in the numbers, or more accurately the distribution of those who had done so by 1913. Although at just under 4,000 the quantity of volunteers exceeded the estimated requirements, 88 per cent of them were distributed across 54 different regiments, making it too complex to integrate them into the regular forces.[57]

- As well as defence against foreign invasion, the Territorial Force was intended to reinforce the regular army overseas after six months training on mobilisation. The force was, however, subject to the same restrictions on overseas service as its predecessors, and deployment abroad therefore relied entirely on members volunteering to do so. Richard Haldane, the Secretary of State for War who introduced the reforms, hoped that between a sixth and a quarter of territorials would. The process by which members could volunteer was formalised in 1910 as the Imperial Service Obligation.[58][59]

Notes

- Irish Times, 10 February 1900. Retrieved 3 December 2008

- "Imperial Yeomanry at regiments.org by T.F.Mills". Archived from the original on May 29, 2007. Retrieved May 29, 2007.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Athawes p. 69

- Mileham pp. 26-27

- Hay p. 172

- Beckett 2011 pp. 200 & 202

- Hay pp. 173-174

- Mileham p. 20

- Amery p. 272

- Hay pp. 45, 175–176 & 217

- Beckett 2011 pp. 202–203

- Mileham 2003 p.27

- Hay pp. 173 & 205

- Hay p. 173

- Athawes p. 74

- Hay p. 181

- Hay p. 194

- Hay p. 175

- Miller pp. 184–186

- Hay p. 189

- Hay p. 190

- Pakenham p. 437

- Hay pp. 189–191

- Hay pp. 173 & 175

- Hay pp.174–177

- Athawes pp. 74–75

- Hay pp. 65 & 177

- Hay pp. 199 & 204

- Hay p. 191–192

- Hay pp. 192–193

- Bennett p. 196

- Bennett pp. 203–206

- Bennett p. 208

- Bennett pp. 209–211

- Hay p. 193

- Hay pp. 175–176 & 193–194

- Bennett pp. 192–193

- Bennett p. 186

- Bennett p. 193

- Hay p. 197–198

- Bennett pp. 194 & 197

- Hay pp. 207–208

- Mileham p. 32

- Hay p. 206

- Hay pp. 4–5 & 175

- Hay pp. 25 & 220

- Hay pp. 26, 171 & 209

- Hay pp. 175 & 211-214

- Beckett 2011 pp. 207–208

- Hay pp. 213-215

- Beckett 2011 p. 208

- Hay p. 218

- Bennett p. 219

- Hay pp. 216 & 220

- Hay pp. 222–224

- Hay pp. 224–230

- Hay7 pp. 238–239

- Beckett 2011 p. 215

- Beckett 2008 p. 32

References

- Asplin, Kevin. The Roll of the Imperial Yeomanry, Scottish Horse & Lovats Scouts, 2nd Boer war 1899–1902, being an alphabetical listing of 39,800 men of these volunteer forces who enlisted for the 2nd Boer war, listing regimental details, clasps to Queens South Africa medal and casualty status . [Limited ed. of 100 copies]

- Asplin, Kevin. The Roll of the Imperial Yeomanry, Scottish Horse & Lovats Scouts, 2nd Boer war 1899–1902, being an alphabetical listing of 39,800 men of these volunteer forces who enlisted for the 2nd Boer war, listing regimental details, clasps to Queens South Africa medal and casualty status . [2nd ed.] Doncaster: DP&G Publishing

- Amery, Leo (2015) [1909]. The Times History of the war in South Africa, 1899-1902. 6. Palala Press. ISBN 9781341184208.

- Athawes, Peter D. (1994). Yeomanry Wars: The History of the Yeomanry, Volunteer and Volunteer Association Cavalry. A Civilian Tradition from 1794. Aberdeen: Scottish Cultural Press. ISBN 9781898218029.

- Beckett, Ian Frederick William (2008). Territorials: A Century of Service. Plymouth: DRA Publishing. ISBN 9780955781315.

- Beckett, Ian Frederick William (2011). Britain's Part-Time Soldiers: The Amateur Military Tradition: 1558–1945. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 9781848843950.

- Bennett, William (1999). Absent Minded Beggars: Yeomanry and Volunteers in the Boer War. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 9780850526851.

- Hay, George (2017). The Yeomanry Cavalry and Military Identities in Rural Britain, 1815–1914. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9783319655383.

- Mileham, Patrick (2003). The Yeomanry Regiments; Over 200 Years of Tradition. Staplehurst: Spellmount. ISBN 9781862271678.

- Miller, Stephen M. (2012). Lord Methuen and the British Army: Failure and Redemption in South Africa. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. ISBN 9780714644608.

- Pakenham, Thomas (1991). The Boer War. Ilford, Essex: Abacus. ISBN 9780349104669.

- Rose-Innes, Cosmo. With Paget's Horse to the Front. London: MacQueen, 1901.

External links

- "Imperial Yeomanry at regiments.org by T.F.Mills". Archived from the original on May 29, 2007. Retrieved May 29, 2007.CS1 maint: unfit url (link) lists all battalions and companies and gives key dates

- Roll-of-Honour.com page; gives additional information about the creation of the Imperial Yeomanry

- UK Government National Archives page on Auxiliary Army Forces (which includes the Imperial Yeomanry)