Il Dottore

Il Dottore (pronounced [il dotˈtoːre], "the Doctor"; commonly known in Italian as Dottor Balanzone or simply Balanzone [balanˈtsoːne]; Bolognese Emilian: Dutåur Balanzån) is a commedia dell'arte stock character, one of the vecchi, or "old men", whose function in a scenario is to be an obstacle to the young lovers. Il Dottore and Pantalone are the comic foil of each other, Pantalone being the decadent wealthy merchant, and Il Dottore being the decadent erudite.[1] He has been part of the main canon of characters since the mid-16th century.[2]

Overview

Il Dottore was born from the city of Bologna, Italy. He is comically inept.[3] He is usually extremely rich, though the needs of the scenario might have things otherwise, and extremely pompous, loving the sound of his own voice and spouting ersatz Latin and Greek. His interaction in the play is usually mostly with Pantalone, either as a friend, mentor or competitor.[4]

History

Il Dottore first originated as the comic foil of Pantalone. The character has his performance origins in the year 1560 with the actor Lucio Burchiella;[5] two other mentions follow soon after, with a pair of vecchi being mentioned in the year 1565,[2] and another mention of Dottore Gracian in 1574.[6] Since his introduction, he has existed in some form or other due to his popularity and interactions with Pantalone,[7] however his popularity did wane in Italy by the 1800s.[5] He has gone by many names besides Il Dottore, those being Dottore Gratiano, Dottore Baloardo ("Dr. Dolt"), Dottore Spaccastrummolo ("Dr. Hack-and-Bandage"),[8] Dottore Scarpazon, and Dottore Forbizone ("Dr. Large Scissor"). His many names reflect his buffoonish nature, and call attention to his positive traits.[3] Il Dottore migrates to France with the Gelosi troupe during the year 1572, still performed by Lucio Burchiella.[9] Since Commedia dell'Arte performers were itinerant by nature, it is only natural that his character was transplanted to other countries. By the late 17th century, Il Dottore was firmly embedded in the public eye, as evidenced by the playwright Molière's inclusion of a Docteur-style character in his play La Jalousie du Barbouillé.[10] In contemporary media, Il Dottore can be found in many common characters, such as Sheldon from The Big Bang Theory[11] and Dr. Zoidberg from Futurama.[12]

Characteristics

Rotund and fond of drink and food but mostly chocolate. Il Dottore is also fond of girls however is untruthful and gets caught cheating several times; he is a love rat. Il Dottore is representative of the learned intellectual class, and as such is meant to playfully parody the educated elite.[13] He attended the University of Bologna, and pretends to be an expert in many subjects, talking constantly, but usually having no idea about that of which he speaks.[14] Depending on the portrayal, however, he can actually be very educated, and bore the other players into leaving the stage.[15] The preferred crowd favorite, however, is the Dottore who speaks nonsense.[16] Il Dottore walks with his chest up, knees bent, and with a bouncy movement, taking small steps;[17] he gesticulates with his hands and fingers, making room around him by keeping others at bay.[17][18] He stands in one position and plants himself to make a point.[17] Il Dottore can be the father to one of the innamorati, usually either Columbina or Isabella.[13][19] There are, however, existing scenarios in which Dottore is not a father, specifically "the Tooth-Puller", or Il Cavadente.[20] There is also precedence for Il Dottore to be cuckolded.[21]

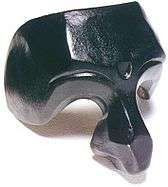

Mask and costume

Unlike the majority of half masks in Commedia dell'Arte, Il Dottore's mask is unique in that it is a one-third mask; the mask itself is meant to be a parody of a Bolognese jurisconsult.[15][17] The actor's cheeks may sometimes have rouge applied to imply that Il Dottore is fond of drinking.[17] His costume is usually all or mostly black and he frequently wears a black felt hat with long, trailing robes.[14][18] Under his black robes are shorter black robes and black shoes.[19] The ruff around Il Dottore's neck didn't come into play until his popularity in France grew, at which point it was adopted in 1653 by Agostino Lolli.

See also

- Giovanni Camillo Canzachi

- Commedia dell'Arte

- Goldoni

- Pantalone

- Innamorati

- Stock Character

References

- Robert Henke. "Improvisation and characters, Individual roles". Performance and literature in the commedia dell'arte. pp. 19–24.

- Jordan, Peter (2015). The Routledge Companion to Commedia dell'Arte. Routledge. p. 62.

- Rudlin, John (1994). Commedia dell'Arte: An Actor's Handbook. Routledge. p. 101.

- Rudlin, John (1994). Commedia dell'Arte: An Actor's Handbook. Routledge. p. 102.

- Sand, Maurice (1915). The History of the Harlequinade. Benjamin Blom, Inc. p. 31.

- Oreglia, Giacomo (1961). The Commedia dell'Arte. Sveriges Radio. p. 25.

- Jordan, Peter (2015). The Routledge Companion to Commedia dell'Arte. Routledge. p. 64.

- https://sites.google.com/site/italiancommedia/the-characters

- Sand, Maurice (1915). The History of the Harlequinade. Benjamin Blom, Inc. p. 37.

- Andrews, Richard (2005). "Moliere, Commedia dell'Arte, and the Question of Influence in Early Modern European Theatre". The Modern Language Review. 100: 448.

- TEDx Talks (2015-11-30), Make 'Em Laugh: Common Ground in Comic Characters | Matthew R. Wilson | TEDxUM, retrieved 2016-12-10

- "COMMEDIA in the modern world". prezi.com. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

- Oreglia, Giacomo (1961). The Commedia dell'Arte. Sveriges Radio. p. 84.

- Ducharte, Pierre Louis (1966). The Italian Comedy. Dover Publications. p. 197.

- Sand, Maurice (1915). The History of the Harlequinade. Benjamin Blon, Inc. p. 33.

- Lea, K.M. (1962). Italian Popular Comedy. Russell & Russell. p. 28.

- Rudlin, John (1994). Commedia dell'Arte: An Actor's Handbook. Routledge. p. 100.

- Oreglia, Giacomo (1961). The Commedia dell'Arte. Sveriges Radio. p. 86.

- Sand, Maurice (1915). The History of the Harlequinade. Benjamin Blom, Inc. p. 32.

- Andrews, Richard (2008). The Commedia dell'Arte of Flaminio Scala. Scarecrow. p. 62.

- Rudlin, John (1994). Commedia dell'Arte: An Actor's Handbook. Routledge. p. 99.

- Rudlin, John; Oliver Crick (2001). Commedia dell'arte. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-20409-5. Retrieved August 4, 2009.

- The Italian Comedy by Pierre Louis Duchartre