Ikun-Shamash

Ikun-Shamash or Iku-Shamash (𒄿𒆪𒀭𒌓)[2] was a King of the second Mariote kingdom who reigned c. 2500 BC.[3] According to François Thureau-Dangin, the king reigned at a time earlier than Ur-Nanshe's of Lagash.[3] He is one of three Mari kings known from archaeology, and probably the oldest one.[2] Another king was Iku-Shamagan, also known from a statue with inscription, in the National Museum of Damascus.[2] The third king is Lamgi-Mari, also read Išgi-Mari, also known from an inscribed statue now in the National Museum of Aleppo.[4][5]

| Ikun-Shamash (𒄿𒆪𒀭𒌓) | |

|---|---|

| King of Mari | |

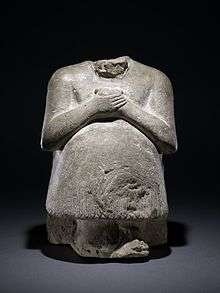

Ikun-Shamash's votive statue, British Museum.[1] | |

| Reign | c. 2500 BC Middle Chronology |

| King of Mari | |

In his inscriptions, Ikun-Shamash used the Akkadian language, whereas his contemporaries to the south used the Sumerian language.[2] His official title in the inscriptions was "King of Mari" and "ensi-gal", or "supreme Prince" of the deity Enlil.[2]

He is known from a statue with inscription, which he dedicated to god Shamash.[2]

Ikun-Shamash's territory seems to have included southern Babylonia.[6]

Statue

Ikun-Shamash's votive statue, set by one of his officials, was discovered in the city of Sippar; the inscription reads:

𒄿𒆪𒀭𒌓 / 𒈗𒈠𒌷𒆠 / 𒑐𒋼𒋛𒃲 / 𒀭𒂗𒆤 /𒅈𒊏𒀭 /𒆪𒅆𒈨𒋤 / 𒊨𒋤 / 𒀭𒌓 / 𒊕𒄸𒁺i-ku-Dutu / lugal ma-ri2ki / ensi2gal / Den-lil2 / ar-raD / tush igi{me}-su3 / dul3-su3 / Dutu / sa12-rig9

"For Iku(n)shamash, king of Mari, chief executive for Enlil, Arra'il his courtier, dedicated his statue to Shamash"

The statue is located in the British Museum.

Statue of Iku-Shamash, King of Mari circa 2400 BCE (in the rear)

Statue of Iku-Shamash, King of Mari circa 2400 BCE (in the rear) The inscription on the statue.[7]

The inscription on the statue.[7]

Statue of Ikun-shamash, British Museum, BM 60828

Statue of Ikun-shamash, British Museum, BM 60828

King Ikun-Shamash of Mari | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by First Kingdom of Mari |

King of Mari 2500 BC |

Succeeded by Iku-Shamagan |

Citations

- Spycket, Agnès (1981). Handbuch der Orientalistik (in French). BRILL. p. 87. ISBN 978-90-04-06248-1.

- Spycket, Agnès (1981). Handbuch der Orientalistik (in French). BRILL. p. 86. ISBN 978-90-04-06248-1.

- Alfred Haldar (1971). Who Were the Amorites. p. 16.

- Photograph in: "Mission Archéologique de Mari 4 vols. in 6. Volume I: Le Temple D'Ishtar. Volume II : Le Palais. Part 1: Architecture. Part 2: Peintures Murales. Part 3: Documents et monuments. Volume III: Les Temples D'Ishtarat et de". Meretseger Books.

- Spycket, Agnès (1981). Handbuch der Orientalistik (in French). BRILL. p. 88. ISBN 978-90-04-06248-1.

- Robert Boulanger (1966). The Middle East: Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Iran. p. 497.

- "Inscription of the statue of Ikun-Shamash". cdli.ucla.edu.

- Jerrold S. Cooper (1986). Presargonic Inscriptions. p. 87.