Iejima

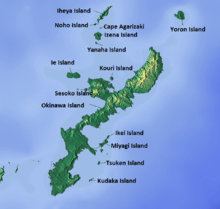

Iejima (伊江島, Iejima, Okinawan: Ii shima), previously romanized in English as Ie Shima, is an island in Okinawa Prefecture, Japan, lying a few kilometers off the Motobu Peninsula on Okinawa Island.[1] The island measures 20 kilometres (12 mi) in circumference and covers 23 square kilometres (8.9 sq mi).[1] As of December 2012 the island had a population of 4,610.[2] Ie Village, which covers the entire island, has a ferry connection with the town of Motobu on Okinawa Island.

| Native name: Iejima (伊江島) | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of Iejima | |

Iejima Iejima in the Ryukyu Islands | |

| Geography | |

| Location | East China Sea |

| Coordinates | 26°42′58″N 127°47′25″E |

| Area | 23 km2 (8.9 sq mi)[1] |

| Coastline | 22.4 km (13.92 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 172 m (564 ft) |

| Highest point | Mount Gusuku |

| Administration | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 4,610 (2012) |

| Pop. density | 200/km2 (500/sq mi) |

Iejima is generally flat.[1] The most notable geographic feature is a peak called Mount Gusuku (or "Tatchuu" in Kunigami) at a height of 172 meters.[1] The mountain resembles a volcano but is actually an erosion artifact. Alternately called "Peanut Island," for its general shape and peanut crop, or "Flower Island," for its abundant flora and more sizeable crop, Iejima draws tourists by ferry, especially during late April when the Ie Lily Festival begins. The Youth Excursion Village accommodates campers for 400 yen a person and includes access to a good beach. The YYY Resort and Hotel located just east of the ferry port is available for those who do not wish to camp.

World War II

American troops from the 77 th infantry division landed on Iejima in April 1945 as part of the Battle of Okinawa and there was heavy fighting from April 16 until the island was secured on April 21. U.S. journalist Ernie Pyle was killed during the battle. There is a monument dedicated to his memory on the southern part of the island. Every year on the weekend closest to his April 18 death there is a memorial service.

Iejima, which was developed in conjunction with US bases on Okinawa, became a naval advance base. Its three airstrips were under Army control, but were used by Naval Air Transport Service. The naval base included 16,700 square feet of general storage and space, 7,475 cubic feet of cold storage space, and 4,500 square feet of open storage. In addition to 700 lineal feet of wharfage, there were repair shops covering 5,500 square feet; hospital, 2,400 square feet; and quarters, 67,692 square feet.[3]:411

Iejima, then called Ie Shima by US military and media, was the major starting point for the Surrender of Japan. It was the home of the 413th Fighter Group which comprised the 1st, 21st and 34th Fighter Squadrons, the 345th Bombardment Group, consisting of the 498th, 499th, 500th and 501st Squadrons, along with the 548th and 549th Night Fighter Squadrons of the 7th Fighter Command. All three groups were stationed there toward the end of the war.

The surrender preparations started on August 17, 1945, with the flight of two Japanese Betty bombers to Iejima where the Japanese emissaries transferred to U.S. Army Air Force C-54s to complete their journey to Corregidor to meet with General Douglas MacArthur's staff. B-25 Mitchells of the 345th were assigned to escort the Japanese bombers from the Japanese mainland to Iejima, and P-38s were assigned the duty of top-cover. Japanese officials ordered the remaining Japanese Air Force to shoot down their own bombers, because they believed that honor required that Japan should fight to the very last person. Instead of flying directly to Iejima, the two Japanese planes flew northeast, toward the open ocean, to avoid their own fighters. One of the Japanese delegates aboard remarked, after looking through a bullet hole in the side of the plane, that a squadron of fighters was approaching and he thought that their surrender mission had failed. However, the squadron of fighters were U.S. P-38 Lightnings assigned as top-cover. The 345th had been directed to send two B-25s as escorts. However, fully aware of the difficulty in communication with the Japanese and correctly anticipating the possibility of necessary deviation from plans, the 345th had dispatched three flights of B-25s so as to bracket the enemy's proposed flight path. This proved to be excellent planning, as only the second of the three flights intercepted the Japanese and the top-cover, off-course and headed on a route that would not have brought them to Iejima. Operating under orders to come no nearer than 305 m (1,000 feet) to the Japanese planes, Major J.C. McClure found it impossible to keep the Japanese on the proper course flying abreast of them, so he pulled out well ahead of them to lead their formation. Seconds later he was surprised to find the Japanese tucked in tightly under his wings. To them it was the safest way to approach the island which had only days before been their target. The four planes arrived over Iejima in perfect show formation.

The Japanese emissaries continued on to the Philippines as planned, concluded the arrangements for the formal surrender scheduled to take place on September 2 in Tokyo Bay, and returned to Iejima on August 18. As the Bettys were taxiing into place to receive their passengers for the return trip to Tokyo, one of them ran off of the runway and broke its landing gear, leaving it unable to continue the trip that day. The Japanese delegation split, with the less important delegates staying on Iejima overnight as the damaged plane was repaired, while the operable aircraft proceeded that evening. For some unexplained reason, that plane ran out of fuel some 210 km (130 miles) from their destination and was ditched in shallow water. The emissaries waded ashore and arrived in Tokyo the next day.

Farmers' Movement

In 1955, the United States military embarked upon a wide-scale campaign to seize land from the farmers of Iejima. The campaign began in 1954 with a so-called survey project. After the island's farmers signed the papers, they realized that in fact they had agreed to their voluntary evacuation. In 1955, the American military landed on Iejima's southern beaches and seized the farmers' lands by force.[4]

Following this seizure, the residents of Iejima began a five decade campaign to oppose the American military. Led by Shoko Ahagon, they traveled throughout the Okinawan islands garnering support for their campaign. This Beggars' March took the islanders all over the prefecture where they were treated hospitably by their fellow Okinawans. However, when they returned to Iejima and started to farm their land once more, the American military razed their crops and arrested the islanders.[4]

In the late 1950s, many residents of Iejima resorted to collecting scrap metal from the military bombing range. This was dangerous work resulting in the deaths or disfigurement of local men.[4]

Today

The United States military maintains a small "auxiliary landing strip" on Ie; this airstrip is now a military training facility run by the U.S. Marine Corps. There is a detachment of 12 US Marines which operates the range. The jobs include Operation Scheduler, Range Warden, Crash/Fire/Rescue, and Motor Transportation. The north-west corner of the island that contains a 1,500 m (5,000-foot) coral runway, a simulated LHD deck, and a drop zone for parachute training.

The three runways that were in use when World War II ended still exist. The center one is now abandoned and is used as a thoroughfare for the locals to get from the north to the south side of the island. The eastern one is now used by a small civilian air carrier, and the western one is still unimproved and is part of the training range.

Cultural references

The island is the setting of a traditional Okinawan drama where a sad girl by the name of Hando-gwaa fell in love with a man named Kanahi, Iejima's headman. When Hando-gwaa learned that Kanahi had already wed she climbed up to Tacchu Mountain and hanged herself with her long, black hair. One can find a statue of this woman in a garden that sits below Gusukuyama.

See also

- Ie Shima Airfield

- Iejima Airport serves the island.

References

- "Iejima". Encyclopedia of Japan. Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2013-01-06.

- 沖縄県の推計人口: 2012年12月 [Population Statistics of Okinawa Prefecture: December 2012] (PDF) (in Japanese). Naha, Okinawa Prefecture: Okinawa Prefecture. 2012. Retrieved Jan 6, 2012.

- Building the Navy's Bases in World War II History of the Bureau of Yards and Docks and the Civil Engineer Corps 1940-1946. US Government Printing Office. 1947.

- Journal, The Asia Pacific. "Beggars' Belief: The Farmers' Resistance Movement on Iejima Island, Okinawa—— | The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus". apjjf.org. Retrieved 2018-08-31.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Iejima. |

- The Battle for Ie Shima

- The True Story of the Japanese Surrender in WW2

- A Closer Look at the Japanese Betty Bombers

- The 34th Fighter Squadron on Ie Shima

Ahagon Shoko and the Farmers