Ibn Bahdal

Hassan ibn Malik ibn Bahdal al-Kalbi (Arabic: حسان بن مالك بن بحدل الكلبي, romanized: Ḥassān ibn Mālik ibn Baḥdal al-Kalbī, commonly known as Ibn Bahdal (Arabic: ابن بحدل, romanized: Ibn Baḥdal; d. 688/89), was the Umayyad governor of Palestine and Jordan during the reigns of Mu'awiya I (r. 661–680) and Yazid I (r. 680–683), a senior figure in the caliph's court, and a chieftain of the Banu Kalb tribe. He owed his position both to his leadership of the powerful Kalb, a major source of troops, and his kinship with the Umayyads through his aunt Maysun bint Bahdal, the wife of Mu'awiya and mother of Yazid. Following Yazid's death, Ibn Bahdal served as the guardian of his son and successor, Mu'awiya II, until the latter's premature death in 684. Amid the political instability and rebellions that ensued in the caliphate, Ibn Bahdal attempted to secure the succession Mu'awiya II's brother Khalid, but ultimately threw his support behind Marwan I, who hailed from a different branch of the Umayyads. Ibn Bahdal and his tribal allies defeated Marwan's opponents at the Battle of Marj Rahit and secured for themselves the most prominent roles in the Umayyad administration and military.

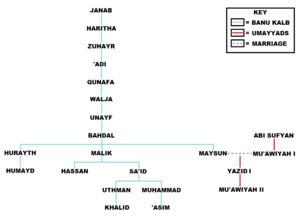

Family

Hassan ibn Malik was a grandson of Bahdal ibn Unayf, chieftain of the Banu Kalb, one of the largest Bedouin tribes in 7th-century Arabia and Syria.[1] Though not a son of Bahdal, Hassan was commonly referred to in medieval sources as "Ibn Bahdal".[1][2] They belonged to the Kalb's princely house, known as the Banu Haritha ibn Janab, which gave Ibn Bahdal prestige and authority over his tribesmen.[1] Moreover, through his aunt, Maysun bint Bahdal, Ibn Bahdal was also a cousin of the Umayyad caliph Yazid I, which increased his influence with the ruling Umayyad dynasty.[1] He later became Yazid's brother-in-law as well.[1]

Career with the Umayyads

Commander and governor under Mu'awiya I and Yazid

Prior to the establishment of the Umayyad Caliphate in 661, Ibn Bahdal fought for a member of the dynasty and governor of Syria, Mu'awiya I, against the partisans of Caliph Ali at the Battle of Siffin in 657.[1] During that battle, Ibn Bahdal was in command of his Quda'a confederate tribesmen from Jund Dimashq (military district of Damascus).[1][3] Later, Ibn Bahdal was among three of Bahdal's grandchildren who dominated the Umayyad political scene during the Sufyanid period;[3] the Sufyanids were descendants of the Umayyad tribe's Abi Sufyan line, which ruled the Caliphate between 661 and 684. Owing to the power of the Banu Kalb and his marital relations with the Sufyanids, Ibn Bahdal was appointed governor over Jund Filastin (military district of Palestine) and Jund al-Urdunn (military district of Jordan) by Mu'awiya I (r. 661–680) and Yazid I (r. 680–683).[1] Ibn Bahdal accompanied Yazid to Damascus, where the latter came to assume the caliphate following Mu'awiya's death.[1] He went on to be an influential voice in Yazid's court.[1]

Role in Umayyad succession crisis

Yazid also appointed Ibn Bahdal's brother, Sa'id ibn Malik, as governor of Jund Qinnasrin (military district of Chalcis).[2][4] This district was dominated by Qaysi tribes resentful of the Kalb's privileged position in the Umayyad court.[2] Sa'id's authority in Qinnasrin was "beyond the endurance of the Qais", according to historian Julius Wellhausen.[2] Under their main leader in the district, Zufar ibn al-Harith al-Kilabi, the Qays ousted Sa'id.[2] Meanwhile, Yazid died in 683 and Ibn Bahdal became the guardian of his young sons,[5] Mu'awiya II, Khalid and Abd Allah.[1] As a result of Ibn Bahdal's influence, Mu'awiya II succeeded his father as caliph, but died of illness in 684, sparking a leadership crisis in the Caliphate at a time when the Mecca-based Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr was recognized as caliph in the Hejaz (western Arabia) and Iraq.[6]

Ibn Bahdal supported Mu'awiya's younger half brothers' claims to succession, though their youth and inexperience generally precluded either of them from being accepted as caliphs by the ashraf (tribal nobility) of Syria.[6] In Syria, the governor of Damascus, al-Dahhak ibn Qays al-Fihri, leaned toward Ibn al-Zubayr, while the governors of Jund Hims (military district of Homs) and Qinnasrin, Nu'man ibn Bashir al-Ansari and Zufar ibn al-Harith al-Kilabi, respectively, the Qaysi tribes in general, and even members of the extended Umayyad family offered their full-fledged recognition of Ibn al-Zubayr's sovereignty.[1][6][7]

Ibn Bahdal fervently sought to maintain Umayyad rule, and by extension, the administrative and courtly privileges of his household and the Banu Kalb.[6] He left his home in Palestine for Jordan to keep a closer eye on developments in Damascus.[1] He assigned Rawh ibn Zinba', a chieftain of the Judham, as his replacement in Palestine, but Rawh was soon after expelled by his rival in the Judham, Natil ibn Qays, who rebelled and gave allegiance to Ibn al-Zubayr.[1][7] Meanwhile, the expelled Umayyad governor of Iraq, Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad, arrived in Damascus and strove to uphold Umayyad rule.[1] However, instead of Yazid's young children, Ubayd Allah turned to Marwan I, a non-Sufyanid member of the Umayyad clan;[6] the latter had been on his way to Mecca to recognize Ibn al-Zubayr's caliphate, but Ubayd Allah persuaded him to return to Palmyra and claim the throne himself.[1]

Ibn Bahdal still favored Khalid ibn Yazid and presided over a meeting of the Umayyad family and the Syrian ashraf, excluding Ubayd Allah, to settle the matter of Mu'awiya II's succession.[1] The meeting was not held in the capital Damascus where al-Dahhak, whose allegiance was still under suspicion, ruled, but in Jabiya, a major town in the Jordan district.[8] Al-Dahhak did not attend the meeting, having been convinced by the ashraf of Qays to boycott and mobilize for war.[8] At the Jabiya summit, Ibn Bahdal declared Ibn al-Zubayr to be a munafiq (hypocrite) who betrayed the Umayyad cause.[7] The attending ashraf agreed, but rejected both Khalid and Abd Allah, saying "we dislike the idea that the others [Qaysi ashraf] should come to us with a shaykh [Ibn al-Zubayr] while we bring them a youngster".[7] After forty days of talks, the Jabiya summit concluded with an agreement nominating Marwan as the new caliph.[8][9] Although Ibn Bahdal's candidate was rejected, he managed to secure a stipulation whereby Khalid would succeed Marwan.[10] Moreover, in exchange for his nomination, Marwan had financial and administrative obligations to Ibn Bahdal, the Banu Kalb and the attending ashraf.[8]

Al-Dahhak, meanwhile, had pitched camp at Marj Rahit, north of Damascus, with the garrison of Damascus, publicly proclaimed his allegiance with Ibn al-Zubayr and renounced the Umayyad dynasty.[11] The Qaysi governors of Qinnasrin and Hims sent al-Dahhak troops, as did Natil ibn Qays of Palestine.[11] Marwan's tribal allies included the Kalb of Jordan, the Kindites and the Ghassanids.[12] While the historian Patricia Crone states Ibn Bahdal was present at Marj Rahit,[3] the medieval historian al-Tabari wrote that Ibn Bahdal "rode off to the Jordan district".[12] In July 684, the two sides fought in the Battle of Marj Rahit, which ended with a massive rout for the Qays and the slaying of al-Dahhak.[8] With this Marwan assumed the caliphate in Damascus while the repercussions of the battle led to a long-running blood feud between Qays and Kalb.[8] In these later battles, the Kalb was led by Ibn Bahdal's cousin, Humayd ibn Hurayth ibn Bahdal.[4]

Later life and death

Medieval sources do not mention if Ibn Bahdal resumed his governorship of Palestine following the Umayyad–Kalbi triumph at Marj Rahit, "but this is clearly not impossible", according to Crone.[4] Marwan died in April 685, less than a year after becoming caliph; however, before his death, he managed to oblige Ibn Bahdal to recognize his son Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan as successor to the Caliphate instead of Khalid ibn Yazid.[10][4] Subsequently, Ibn Bahdal's influence gradually receded.[10] He supported Abd al-Malik against the Umayyad rebel Amr ibn Sa'id al-Ashdaq and was in the company of the Umayyads who witnessed Amr's execution.[10][4] According to Lammens, "After this event no more is heard of this Kalbi chief who had, at one juncture, been the arbiter of the destinies of the Umayyad dynasty."[10] Ibn Bahdal likely died in 688/89.[10]

References

- Lammens 1971, p. 270.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 170.

- Crone 1980, p. 93.

- Crone 1980, p. 94.

- Lammens 1966, p. 920.

- Kennedy 2004, p. 78.

- Al-Tabari, ed. Hawting 1989, pp. 49–50.

- Kennedy 2004, p. 79.

- Lammens 1971, pp. 270–271.

- Lammens 1971, p. 271.

- Al-Tabari, ed. Hawting 1989, p. 56.

- Al-Tabari, ed. Hawting 1989, p. 59.

Bibliography

- Crone, Patricia (1980). Slaves on Horses: The Evolution of the Islamic Polity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52940-9.

- Kennedy, Hugh N. (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow: Pearson Education Limited. ISBN 0-582-40525-4.

- Lammens, Henri (1960). "Baḥdal". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 919–920. OCLC 495469456.

- Lammens, Henri (1971). "Ḥassān b. Mālik". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 270–271. OCLC 495469525.

- Al-Tabari (1989). Hawting, G. R. (ed.). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 20: The Collapse of Sufyanid Authority and the Coming of the Marwanids: The Caliphates of Mu'awiyah II and Marwan I and the Beginning of the Caliphate of 'Abd al-Malik. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Wellhausen, Julius (1927). The Arab Kingdom and its Fall. Translated by Margaret Graham Weir. Calcutta: University of Calcutta. OCLC 752790641.