Iberian Gates

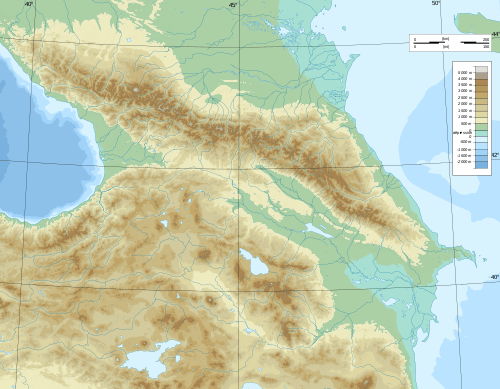

The Iberian Gates (Georgian: იბერიის კარი, Turkish: Gürcü Boğazı) is situated in the westernmost extension of historical Georgia (Zemo Kartli), on the plateau of the Mescit Mountains (Mount Uzundere), known as the Meschic mountains in Greco-Roman geography. The place is recorded as Gurji-Boghazi (საქართველოს ყელი) in the Description of the Kingdom of Georgia by 18th century, Georgian geographer Vakhushti Batonishvili.[1]

In history

Alexander's invasion of Iberia, remembered not only by the Georgian historical tradition, but also by Pliny the Elder (4.10.39) and Gaius Julius Solinus (9.19), appears to be memory of some Macedonian interference in Iberia, which must have taken place in connection with the expedition mentioned by Strabo (11.14.9) sent by Alexander in 323 BC to the confines of Iberia, in search of gold mines.[2] Alexander reportedly brought Azoy (Azo). together with followers, to Mtskheta and established Kingdom of Iberia. Azo pulled down all fortresses in the land of Iberia, leaving four fortresses [standing] at the "gates of Iberia", and filling them with soldiers.[3] In the 4th-3rd centuries BC area was part of the Iberian Kingdom as noted by Strabo.

It was at this pass that the general Pompey (106-48 BC), as the result of the Roman campaigns against Pontus had halted his legions in 65 BC, in his attempts to pursue the defeated King Mithridates VI Eupator over the Caucasus. Pompey judged that his legions had reached the edge of the world.[4] The Romans were said to have attempted to block the ravine's mouth with defensive wooden and iron-bound gates as recorded by the classics. The Iberian gates led to quicker access into the Roman province of Greater Armenia, whenever necessary in military operations. During Byzantine–Sasanian wars (421–422), the Iberian gates had come into the possession of the Huns. Kavadh I with help of Vakhtang I of Iberia seized and fortified it, though less as a precaution against the Romans than against the Huns and other northern barbarians.[5] Once the Hundred Years Peace between Sassanian Persia and Byzantine collapsed, Kavadh I summoned Vakhtang as a vassal to join in a new campaign against Byzantine. However, Vakhtang refused, provoking a successful Iranian invasion of Iberia, where he was defeated. On the decline of the Persian power, the Iberian frontier was the scene of the operations of the emperors Maurice and Heraclius. According to treaty in A.D. 928 it passed to Georgian Bagratids. Between the 13th and 17th century it was part of the Georgian principality of Samtskhe, latter was annexed by Ottoman Empire in 1550.

See also

References

- Vakhushti Prince (Bagrationi). Geography Georgia., 1904, Tiflis.

- Toumanoff, p. 9

- Licini, Patrizia (2017). Surveying Georgia’s Past. p. 136.

- Flynn, Thomas S. The Western Christian Presence in the Russias and Qajar Persia, C.1760-C.1870. Brill, 2016.

- Smith, W., Grove, G. and Müller, K. (1872). An historical atlas of ancient geography, biblical and classical. London: John Murray.