Huwwarin

Huwwarin (Arabic: حوارين, also spelled Hawarin, Huwarin or Hawarine) is a village in central Syria, administratively part of the Homs Governorate, south of Homs. Situated in the Syrian Desert, the village is adjacent to the larger town of Mahin to its south and lies between the towns of Sadad to the west and al-Qaryatayn to the east.[1] Its inhabitants are predominantly Muslims.[2]

Huwwarin حوارين Hawarine | |

|---|---|

Village | |

| Hawarin | |

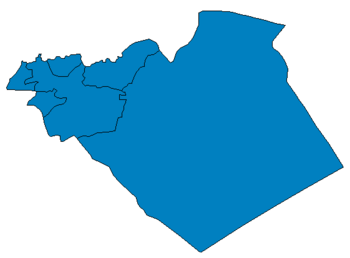

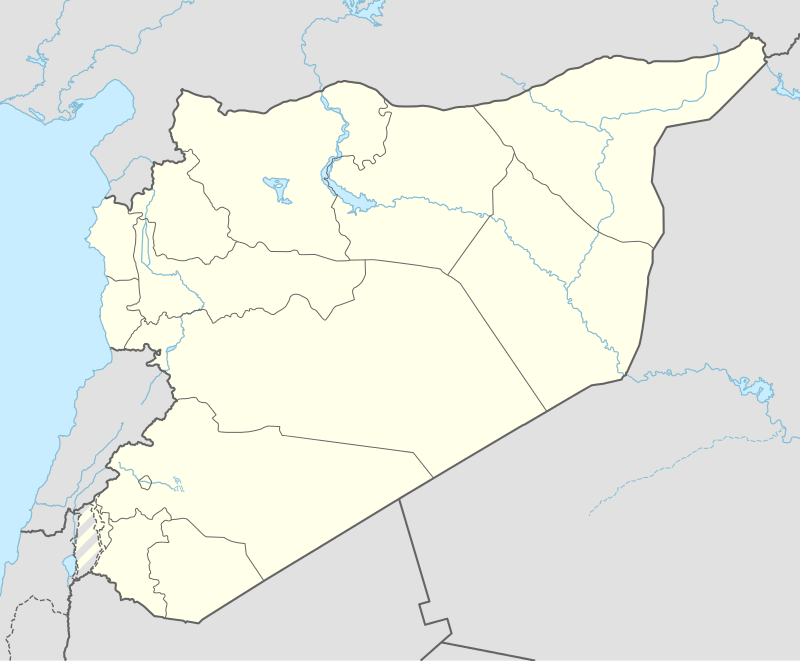

Huwwarin Location in Syria | |

| Coordinates: 34°16′0″N 37°4′0″E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Homs |

| District | Homs |

| Subdistrict | Mahin |

| Population (2004) | |

| • Total | 1,802 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | +3 |

History

Classical period

Huwwarin was an important town during the Byzantine Empire-era in Syria when it was known as "Evaria," "Euaria" or "Aueria." The name "Hawarin" was also used according to Syriac inscriptions between the 4th and 6th centuries CE.[3] The Byzantines set up army units in the town.[4] A diocese was centered on Huwwarin in 451 CE.[5] It later became a titular see of Phoenicia Secunda. According to Ptolemy, it was a part of the Palmyra district.[3] The Ghassanids, who were Arab Christians, dominated Huwwarin and their first official bishop, John of Evaria, was from the town. By 519 there was at least one church in the town.[6]

In the late 6th-century Magnus the Syrian, a prominent aristocratic figure in Byzantine Syria and close ally to emperors Justin II and Tiberius II, built another church in Huwwarin as well as a wall surrounding it.[7] He owned property in Huwwarin and financed many of its construction projects at the time. It was made a city in 573 by the Byzantines.[5] In 581 Magnus invited the Ghassanid phylarch ("king") al-Mundhir III to the consecration of the newly constructed church in Huwwarin before seizing him on behalf of the emperor. Al-Mundhir had been accused of treachery by Mauricius, a high-ranking secretary of Tiberius, and Magnus had him, his wife and three of his children arrested upon arrival in Huwwarin, then sent to Constantinople.[8]

Consequently, the Ghassanids revolted against the Byzantines in Syria, Palestine and Arabia under the leadership of Mundhir's son al-Nu'man VI.[9] Following Magnus's departure from Huwwarin, al-Nu'man's troops raided and conquered the city. They slayed a number of its residents, took captive the rest and plundered Huwwarin of its gold, silver, brass, iron, wool, cotton, corn, wine, oil, cattle, sheep and goats.[10] According to Byzantine historian George of Cyprus, by the 6th-century, Huwwarin was a suffragan see of Damascus.[3]

Islamic era

In the summer of 634, during the Islamic conquest of Syria, the Muslim army of general Khalid ibn al-Walid reached Huwwarin following their capture of al-Qaryatayn and raided the town's cattle. Bolstered by reinforcements from Baalbek and Bosra, Huwwarin's residents resisted Khalid's troops, but were quickly defeated in the minor battle. Afterward, some of the town's defenders were killed while others were taken prisoner.[11][12]

Part of Jund Hims ("Military District of Hims"), Huwwarin flourished during the roughly 90 years of Umayyad Caliphate rule (661-750) and remained populated by Ghassanid Christians.[13] It was the favorite recreation spot of the second Umayyad caliph Yazid I (680-683),[6] who drank and hunted there.[14] The caliph resided in Huwwarin frequently and died and was buried in the town on 11 November 683.[6][15]

Syrian geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi visited the town in 1226, during Ayyubid rule in Syria and noted that it was "a fortress near Hims."[16]

Modern era

By the 19th-century, Huwwarin was a small Muslim village.[17] Irish missionary William Wright visited it and noted that the town was locally famous for "its seven splendid churches," although most of them were bare remains. He wrote that the largest church was rectangular in shape, 46 meters (151 ft) by 38 meters (125 ft) and over 9 meters (30 ft) high. It consisted of a central hall with three rooms on each side and fragments containing Greek inscriptions.[18] It apparently grew to being a large village by the beginning of the 20th-century according to the 1909 Catholic Encyclopedia."[3]

It was described as "a doleful agglomeration of old buildings, including a very well preserved Byzantine fort and the remains of two churches."[19] Huwwarin was excavated in 2003-04.[20]

References

- General Census of Population and Housing 2004 Archived 2013-01-12 at Archive.today. Syria Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). Homs Governorate. (in Arabic)

- Smith; in Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, Second appendix, B, p. 174

- Herberman, 1909, p. 572.

- Eph'al, p. 149.

- Jones, p. 1365.

- Shahid, 2002, p. 152

- Haldon, 2010, p. 182

- Haldon, 2010, p. 183

- Greatrex, p. 166.

- Oriental Explorations and Studies, 1928, p. 38.

- Hitti, p. 171. Translating al-Baladhuri.

- Tabari, 1993, p. 110.

- Shahid, 1995, p. 268.

- Shahid, 1995, p. 32.

- Houtsma, 1987, p. 1162.

- le Strange, 1890, p. 456

- Porter, 1858, p. 550.

- Wright, 1895, p. 31

- Boulanger, 1966, p. 341.

- Shahid, 1995, p. 349.

Bibliography

- Boulanger, Robert (1966). The Middle East, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Iran. Hachette.

- Eph'al, Israel (1982). The Ancient Arabs: Nomads on the Borders of the Fertile Crescent, 9th-5th Century B.C. BRILL. ISBN 9652234001.

- Haldon, John F. (2010). Money, Power and Politics in Early Islamic Syria. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0754668495.

- Herberman, Charles George (1909). The Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church. 5. Robert Appleton company.

- Hitti, P.K. (1916). The Origins of the Islamic State, Being a Translation from the Arabic, Accompanied with Annotations, Geographic and Historic Notes of the Kitâb Fitûh Al-buldân of Al-Imâm Abu-l Abbâs Ahmad Ibn-Jâbir Al-Balâdhuri. 1. Columbia University.

- Houtsma, M.H. (1987). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam. BRILL. ISBN 9004082654.

- Jones, A.H.M. (1971). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. 3. University Press.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. OCLC 1004386.

- Oriental Explorations and Studies. Oriental Explorations and Studies. 1928.

- Porter, J.L. (1858). A Handbook for Travellers in Syria and Palestine. 1. Murray.

- Shahid, I. (2009). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, Part 2. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0884023478.

- Shahid, I. (2002). Toponymy, Monuments, Historical Geography and Frontier Studies. 21. Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 0884022846.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Tabari (1993). K.Y. Blankinship (ed.). The Challenge to the Empires. SUNY Press. ISBN 0791408515.

- Wright, William (1895). An Account of Palmyra and Zenobia: with Travels and Adventures in Bashan and the Desert. T. Nelson and Sons.